Ensign Roger S. Norton Jr. U.S. Naval Aviator.

Meet LT Roger S Norton Jr, U.S. Navy Reserve and Cranford 86 Hero

By Stu Rosenthal and Don Sweeney with Bob Lopez

As we march into a new year profiling the brave young men who sacrificed their lives in defense of freedom, we find ourselves profiling a naval aviator from Cranford, NJ who perished New Year’s Day, 1943. Following our prior tributes about local pilots, some may now believe aviators are common in the U.S. military. Let us remind you, the qualifications are high, and the training is difficult. The fact that so many Cranford young men achieved this prestigious designation is a credit to our town and its ability to nurture such fine young men. This month, our Hometown Hero is Lieutenant Roger Norton Jr., pilot of a maritime patrol aircraft, the PBY Catalina flying boat.

Since we began this journey in 2016, our stories have followed the collection of documents, anecdotes, pictures and a timeline of a brave young man known to Cranford. Much of this story, however, will be recited by a proud Gold Star father, Roger S. Norton Sr. He left behind a touching tribute to his son in a note we retrieved at the Cranford Historical Society. It was written on letterhead denoting their home on 22 Central Ave in Cranford. Roger Jr. was the second fatality from Cranford during World War II, but perhaps its first combatant, patrolling the U-boat-infested Atlantic Ocean months before the U.S. was officially at war.

Roger Jr. was born in Brooklyn, NY on April 9th, 1919, and then moved to Freeport, NY. Before the Norton family settled in Cranford in 1928, Roger likely attended private schools in Norwich, VT and Hanover, NH. In 1932, he completed eighth grade at Roosevelt School, and was enrolled at Cleveland School on North Union Ave., which was Cranford’s high school until 1938. Roger was in the same class as Alan Okell, another Cranford 86 Hometown Hero aviator that we recently profiled, and whose namesake street is located next to Roger Norton Place in the Indian Village section of Cranford.

Roger Norton’s Portrait and Profile from his 1936 yearbook.

Roger Norton Sr’s passage follows: “While in high school, Roger was one of the editors of the Spotlight [school newspaper] and Editor in Chief of the 1936 ‘Golden C’ [yearbook]. He was awarded Honorable Mention for New Jersey in the Literary Division – Quill and Scroll Column Award of the Scholastic Awards, National High School Competition, a National Scholastic Award. His athletics included tennis and a place as ‘Goalie’ on the Cranford High School hockey team.

At nineteen, Roger was approaching completion of his Junior year at the University of Michigan [where he was studying English]. His scholastic standing was good, but he felt that writing, his prospective career, demanded somewhat more experience in living than he had yet attained, and he set out to gain such experience, intending to return later and finish his college work. He regarded Naval Aviation as a likely field for such experience and began his training as a Naval Aviator in Oakland, California, in the Spring of 1939. His further training was at Pensacola, Florida, then the ‘Annapolis of the Air’ and it was there that he received his ‘Wings’ and his commission as an Ensign in the United States Naval Reserve in March, 1940.

The arm patch that would have been worn by Roger S. Norton Jr.

Assigned first to Patrol Squadron 52 (later designated Patrol Squadron 72), he was stationed initially at Charleston, South Carolina, then at Norfolk, Virginia, and later Quonset Point, Rhode Island. His group was part of the Atlantic Patrol prior to our entry into the war. Among his other tasks at this time, he and another Ensign prepared jointly A Course of Study in Patrol Seaplane Navigation, which was used in instructional work by our Navy.

While at Quonset Point, his Squadron was assigned the task of providing an air convoy for the vessels which were then transporting our troops to Iceland and also participated in the search for the [German battleship] Bismarck. He was designated a Patrol Plane Commander in November, 1941. When we entered the war, his Squadron immediately was sent to the Pacific area and was stationed at Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Base, Hawaiian Islands.

He was appointed Lieutenant (junior grade) on May 27, 1942 and shortly thereafter was assigned to duty in the South Pacific. It was at about this time he was selected as the pilot to transport Admiral Nimitz on a tour of the area, which may be regarded not only as a signal honor, but also as concrete evidence of his recognized ability as an aviator. On October 1, 1942 he was appointed a full grade Lieutenant. His duties as a Patrol Plane Pilot were largely those of reconnaissance and rescue work. In line with such duties, he saw active service in several of the major battles of the Pacific.

Our research and narrative could not offer a better tribute to the character and sacrifice of Roger Norton Jr. Yet, the historical significance of his participation in the Atlantic patrol operations – conducted well before the U.S. officially declared war – merits a closer look. When Norton reported to Charleston in 1940, the new aviator joined a patrol unit that was busy conducting U-boat sweeps deep into the neutral waters of the Atlantic. Later, key agreements signed with Britain would commit the U.S. to “short-of-war” naval operations.

In 1941, Norton’s unit began training in Norfolk with submarines, as military cooperation between the U.S. and Britain accelerated. U.S. policy had now guaranteed security in the Western Hemisphere, which included protecting maritime shipments to Britain. By May, Norton deployed to the Naval Station Argentia in Newfoundland, Canada, for final training before patrols would commence for protecting transatlantic convoys.

An actual photograph of a PBY Catalina flying boat from Roger Norton’s Patrol Squadron 72.

The PBY was uniquely suited for patrol operations. With a range of 2500 miles without refueling, and the ability to carry enormous loads of depth charges, torpedoes and traditional bombs. It was a daunting weapon to engage German U-boats which were stalking British supply convoys. But it could also take off and land in the water – an ideal craft for rescuing downed pilots. Designed and manufactured by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, it was yet another American engineering marvel that contributed to wartime victory.

In May 1941, Hitler’s pride of the fleet, the Bismarck, debuted in the Atlantic. Fearful it might disrupt the delivery of critical supplies, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill unleashed the Royal Navy, to hunt for the world’s largest and most heavily armored battleship. The PBYs were then ordered from both sides of the Atlantic, from Newfoundland to Great Britain, to conduct vast sweeps in search of the German ship. On May 24th, the Bismarck was attacked and damaged, but not before sinking the HMS Hood, a flagship British vessel believed unsinkable. Churchill vowed to avenge its loss, and the lives of over 1400 British sailors.

Just days after arriving at Argentia, Norton’s squadron was conducting routine training when it was abruptly recalled to the USS Albemarle, its escort ship. The aircrews were advised of a long, secret reconnaissance mission over the Atlantic, in search of the Bismarck. They were also warned of bleak weather, and harsh flying conditions (see photo). Four PBY aircraft from Norton’s unit departed at 2:40 pm, followed by another seven at 5:20 pm. The first group approached the search area southwest of Greenland around dusk and observed no vessels through the mustering fog. They were ordered back in icing weather. The second group flew through the fog and darkness to the assigned area. They searched for the German battleship, before turning around, empty-handed.

Back at Argentia, the thick, low fog made landing unsafe and planes with sufficient fuel were ordered south. Disoriented, the PBY pilots became dispersed, and set down in the waters surrounding Newfoundland. One crew disembarked near Anticosti Island, and rowed ashore in a yellow raft, seeking assistance. The isolated inhabitants, who only spoke French, ran away, scared of the oddly dressed aircrew. Ironically, the locals had encountered a group of Germans a few years prior who sought to purchase their island under the guise of representatives of the wood pulp processing industry. Many speculated that they were Nazi agents seeking to gain a strategic military air field on the island. Now, the frightened natives believed the innocuous fliers from Patrol Squadron 52 were returning Nazi invaders. Seemingly, Ensign Roger Norton Jr may have been among this bewildered U.S. aircrew stuck on Anticosti Island. By the next day, however, Norton’s squadron had been safely reunited at Argentia.

Roger Norton Place in the The Indian Village section of Cranford dedicated in memory of the World War 2 Hometown Hero. Note the Blue Star emblem at the bottom

Ensign Norton and his patrol squadron had been early participants in the greatest air-sea pursuit in naval warfare history. Forty British ships began searching the vast waters of the Atlantic for the elusive Bismarck. Finally, on May 26th, an American PBY pilot/advisor secretly flying with a British aircrew from Northern Ireland spotted the damaged Bismarck listing, or tilting, about 700 miles offshore. By the next day, surrounded by the Royal Navy, the largest and most ironclad battleship at the time was bombarded. Just days after her maiden voyage, the Bismarck was sunk, and over 2000 German sailors died.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a national emergency, using the Bismarck incident to express the seriousness of the German threat. But U.S. involvement remained controversial and covert since Roosevelt was acting outside of a congressional policy of neutrality. Later, President Roosevelt would state that if the U.S. Congress knew of his actions, he would have been impeached.

Detachments from Norton’s unit began rotating between Rhode Island for training exercises and Newfoundland for convoy escort operations. Preparations for war had intensified and the risks mounted. In July, deployments began to a new U.S. base in Iceland, despite proximity within Germany’s declared war zone. With the start of escort-of-convoy patrols in September, U.S. fatalities followed. Eleven sailors died aboard the USS Kearney after it was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Another 100 were lost when the USS Reuben James was sunk by the Germans. Consequently, throughout most of 1941, Ensign Norton, his patrol squadron and the U.S. Navy were engaged in an undeclared Atlantic war against Germany.

Roger Norton Sr.’s letter continues: At the time of Roger’s death, he was stationed in the Solomon Islands and had been assigned the task of flying to the rescue of an Army pilot who had been forced down at sea off the island of New Georgia. His mission successfully accomplished, he was on his way back to his base and was about to set his flying boat down just off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal, when a small landing craft darted directly across his path. By swerving sharply to one side and at the same time upward he avoided a collision with the landing craft, but in doing so his plane lost momentum and crashed into the sea. He was instantly killed in the crash, as were also three members of his crew. The plane sank in such deep water and so quickly that his body could not be recovered.

Roger S. Norton Jr., the aspiring writer searching for seafaring adventures that could provide perspective for his future work, had accomplished only some of his goals. We can only imagine what great writings would have flowed from his pen. He was an American hero and among the first Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes engaged in World War II combat operations. We thank the residents of Roger Norton Place and Alan Okell Place for sponsoring the banners for these two Cranford High School Class of 1936 classmates. Go to Cranford86.org for links to our research sources and YouTube video links pertaining to this month’s story.

For information on our project, or to sponsor a banner of a Cranford 86 hero, please call Don Sweeney at 908 272-0876.

Go to Cranford86.org for YouTube links to more history about the PBY flying boat and the hunt for The Bismarck.

The PBY Catalina flying boat. A history a YouTube clip.

A fine young man, Roger’s grade school portrait.

The Golden C staff from Cranford’s Yearbook from 1936. Roger Norton Jr. was Editor in chief of both the Cranford Yearbook as well as the Spotlight Cranford High School’s newspaper.

A photograph of a memorial service in 1941 for a crew from Roger Norton’s Patrol Squadron which went missing and were never found. It’s an amazing research find.

1. A design drawing of a PBY-5, like one flown by Ens. Roger S. Norton Jr. while serving with VP-52 in 1941. Note the front and side gun turrets. 2. The wing ends turned down to act as floats for take-off and landing stability.

In a letter found at The Cranford Historical Society, Roger Norton’s father detailed the life of his son through to his death at Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. One note that he made was that he donated his son’s naval officer’s sword to the society. We found it wrapped carefully in their archives at The Hanson House on Centennial Ave.

The sword had incredible detail especially in the handle which seems to be made of coral with dolphins and eagles embossed on several places on the sword and scabbard.

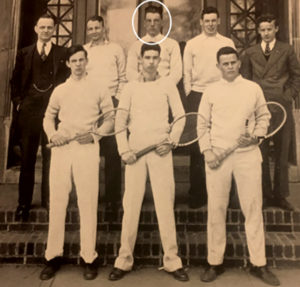

Roger Norton pictured with his 1936 Tennis team on the steps of Cleveland High School.

Roger Norton’s High School Hockey team 1936 from The Golden C Cranford yearbook. Norton was the goalie

The Bismarck, Hitler’s attempt to dominate the sea and the British Navy. It was the largest and most powerful sea-based force on earth, 50,000 tons ,25% larger than the international treaty allowed. One sixth of a mile long, 120 feet wide it could move at nearly 40 miles an hour. With 13-inch steel armor and eight 15-inch guns able to hurl a 2000 pound shell accurately over 20 miles. It was the fastest, largest most powerful ship of its time. No ship ever built, even to today, was larger and more powerful than the Bismarck. It was considered unsinkable.

It was found in The North Atlantic by an American PBY pilot, one of Roger Norton Jr.’s comrades, and sunk by the British Navy one week into its maiden voyage.

The search and sinking of the Bismarck.