(above) Eugene McGarry’s formal naval portrait after receiving his gold Naval Aviator wings.

Ensign Eugene G. McGarry, U.S. Naval Aviator and Cranford 86 Hero

By Stu Rosenthal with Don Sweeney and Lt. Col. Steve Glazer (USA, Ret.)

(above) A young officer-in-training Eugene McGarry during happy times.

The snowiest Cranford winter in memory melted into tears for young Jacquelin (Gearrick) Ellis in frigid January of 1945. Eleven-year-old Jacky arrived home from school for lunch and entered the house, perhaps still brisk because of the coal shortage. Jacky was startled, her mom inconsolable. Elizabeth McGarry Gearrick was just informed that son Gene was missing at sea. Just weeks earlier, Jacky ran down the driveway excited to see half-brother Gene, home on a limited pass before Christmas. They shared mom’s homemade pies and ice-skated on the nearby frozen river, but it was all too brief. By May, when winter was long forgotten and Europe was liberated, another chill descended upon Cranford. Mrs. Gearrick was informed that twenty-two-year-old Gene would never return home. Similar stories of Cranford families devastated by lost service members were too often recounted during the war. For Mrs. Gearrick and her family, the episode was nearly repeated that year when her oldest son Walt was twice wounded while serving in the South Pacific. These narratives were recently shared with us by Jacky, now eighty-five years old, who still resides in Cranford only a few blocks from her childhood home. She also led us to her younger brother Warren, now eighty-one years old, and retired in North Carolina. Warren recalled a time as a young boy when he and Gene would lay back in a local hay field, gaze overhead and fantasize about flying. Remarkably, Warren then spent his career as a pilot with Eastern Air Lines (since defunct), assured a “guardian angel” escorted him on every flight. Eugene George McGarry was born Aug. 18, 1922, to Walter and Elizabeth McGarry in Chicago, IL. Following the death of Walter Sr. from pneumonia when Eugene was very young, Elizabeth remarried and eventually settled in Cranford with older son Walter Jr. (‘Walt’) and Eugene (‘Gene’). Jacquelin (‘Jacky’) was born a few years later, followed by Warren. As a boy, Gene attended Roosevelt Elementary School and received communion at St. Michael Church. An unbounded curiosity fed Gene’s varied interests, which included scouting, flowers, books, the school newspaper and model boats and planes. He was voted into the National Honor Society at Cranford High, where he had joined the science and aviation clubs, and graduated in 1939 when only sixteen. He attended Union Junior College followed by Cooper Union College of Engineering. Gene also spent time in Oregon on environmental projects with the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. Before enlisting in the US Naval Reserve in Oct. 1942, Gene was working in nearby Kearny in the engineering department of Western Electric, which was supplying half of all military radar electronics. Gene dreamed of flying and had applied to the Navy’s highly competitive aviation training program. He had the fortitude, having spent part of his early childhood in a Newark orphanage.

(above) Eugene McGarry dressed for work in the traditional Navy aviator flight uniform including goggles.

He also had the intelligence ‘bug,’ as joked recently by his family, and may have skipped a grade in school. But Gene still needed to prove to the Navy he had the ‘right stuff.’ He appeared before a selection board for intensive psychological and medical examinations in Dec. 1942. Gene successfully completed a battery of tests, met the qualifications and was sworn in as a cadet in the Navy’s V-5 program, an aviation and officer training program. Cadet McGarry arrived at the Navy’s Pre-Flight School at Chapel Hill on the campus of the University of North Carolina in March 1943. This demanding three-month screening program involved intensive physical training, athletics and indoctrination in basic military and naval disciplines. Future President George H.W. Bush had just completed the same pre-flight training, an experience he would later say “shaped his life.” Led by expert instructors and demanding coaches, many cadets failed the rigorous program and would serve elsewhere in the Navy in a non-flying enlisted job. After passing pre-flight training, Gene arrived for Primary Flight School at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, FL. He was introduced to flight, acrobatics and night flying. In addition to classroom instruction, Gene learned how to fly with instruments and as part of a formation. Many classmates failed the training but Gene progressed to intermediate flight training. By fall 1943, Gene was flying mostly with instruments or ‘blind flying.’ He learned how to recover from an engine stall, a flipped plane and a descending spin. As the pool of qualified cadets narrowed further, Gene continued to advanced flight school where he learned dive-bombing runs, fighter approaches, live firing and underwater egress. By March 1944, with over 500 total flight hours, McGarry had earned the coveted ‘Wings of Gold’ worn by naval aviators and was commissioned an ensign in the US Naval Reserve. Those with top gunnery skills also qualified for subsequent fighter training. This select group included Gene. Conceived before the US entered the war, the Grumman F6F ‘Hellcat’ was developed in Bethpage, Long Island as a carrier-based fighter with greater speed, armament and firepower than its predecessor. The single-seat, single-engine Hellcat vastly improved contests against the Japanese A6M ‘Zero,’ the most common enemy aircraft encountered by US Navy fighter pilots. By the end of the war, Hellcat pilots were credited with 5155 overall kills compared to just 270 losses, an unparalleled 19:1 win-to-loss ratio. Following graduation from Pensacola in March 1944, Ensign McGarry began operational training at NAS Atlantic City. Not too far from home, McGarry had arrived at the newest premier training facility for naval fighter pilots. He was taught advanced gunnery, combat tactics and fighter navigation. Ensign McGarry learned how to catapult and land on aircraft carriers, dodge enemy aircraft and initiate a dogfight. The Cranford kid who adored the Iris flower had transformed into a genuine, perhaps cocky fighter pilot. Gene was known to visit the Cranford skies unannounced. According to Jacky and Warren, he would buzz low or strafe over their house at 408 Manor Ave. in a Corsair airplane, but discontinued once a neighbor complained to police. The summer heat swelled in 1944 and Gene may have been itching for an even greater challenge. He was accepted for specialized ‘night fighter’ training and reported on Aug. 8, 1944 to Charlestown Naval Auxiliary Air Field near Quonset Point, RI. The US fleet faced a daunting task early in the war — how to counter Japanese air attacks. Ships were particularly vulnerable at night, often unable to mount a defense or respond with anti-aircraft gunfire unless the enemy could be heard or visibly sighted. The British were having early success with new radar technology for tracking incoming warplanes, which provided early warning and time to launch a counterattack. Now, the US Navy sought to develop an airborne version of radar, intended for bombing, ship detection and air superiority.

(above) Gene McGarry posing in the open cockpit of a “Yellow Peril,” a double-winged biplane used in training.

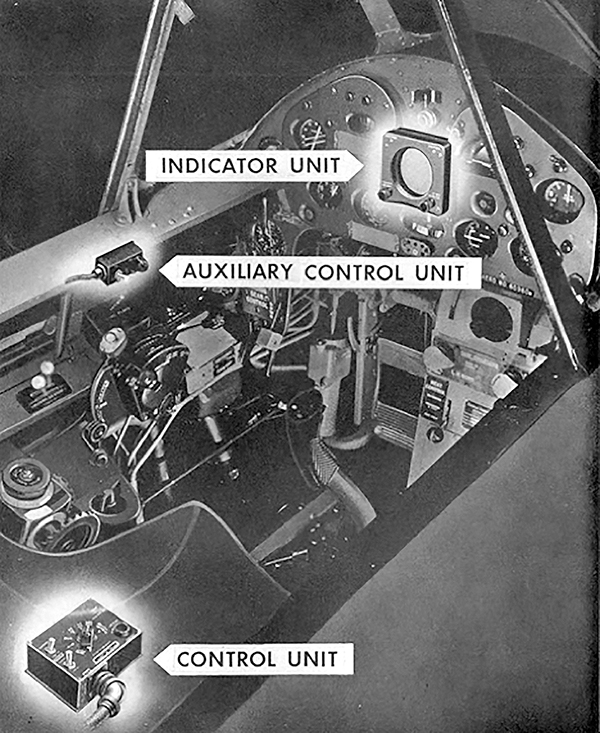

The Navy believed radar could be affixed to fighter planes to hunt enemy aircraft from miles away, under the veil of the night sky. Ensign McGarry’s new training unit was conceived from a top-secret program begun early in the war to develop a night fighter capability with tactics that could protect US ships from enemy attack. Working with top engineers from industry and MIT scientists, the Navy ordered Hellcats modified with radar and enhanced instruments so it could fly missions around the clock. By the end of the war, night fighter Hellcats were credited with protecting carriers from nighttime enemy attacks and suppressing lethal Kamikaze attacks. Night fighting required novel and distinct skills, even among top naval aviators. A pilot needed to balance conventional daytime fighting and making visual contact with the enemy, against nighttime fighting and relying solely on radar and cockpit instruments. In his Hellcat, Gene would plunge from the clouds like a nocturnal bat or zoom forward only feet above the breaking waves. On moonless nights, he practiced how to detect, intercept and destroy enemy aircraft. In preparation for combat, Gene would render split-second decisions soaring above the open seas at speeds near 400 mph. Ensign McGarry remained at Charlestown through Dec. 1944. After a brief visit home, he left San Diego aboard the aircraft carrier USS Bennington on New Year’s Day 1945. One week later, he arrived at Pearl Harbor, greeted by an armada of US carriers and battleships. With nearly 300 flying hours under his belt in the Hellcat, Ensign McGarry arrived at the ‘finishing school’ for night fighter training in the Pacific — NAS Barbers Point, HI. Near the end of his first week, he wrote home to his mom and family. It was his last letter. On January 12, 1945, following two years of intensive naval training, Ensign Eugene G. McGarry flew for the final time. He was piloting an F6F-5N Hellcat practicing night strafing maneuvers at sea with other pilots from his squadron. According to the Navy accident report, the night was “exceptionally dark” and Ensign McGarry was in a steep dive. His wingman believed he never pulled out or maneuvered the plane horizontally before it crashed into the sea. McGarry and his aircraft were never recovered.

(above) The arm patch that would have been worn by Gene’s night fighter training unit in the Pacific. Note the reference to the night flying bat with the radar antenna on its right wing.

When word circulated in Cranford about the loss of Gene, Mrs. Leonora Sjursen called on his family to offer comfort and support. Mrs. Sjursen, also a Gold Star Mother, had lost her son Paul just 11 months earlier. (A prior Cranford 86 article featured Corporal Paul Sjursen.) A mass was offered at St. Michael Church in May 1945 and repeated annually by Mrs. Gearrick. Ensign Eugene G. McGarry is forever memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. Brother Walt survived his battle wounds, returned to Cranford, married and named his son after Eugene. Jacky remained in Cranford and at a recent Memorial Day ceremony, thanked the Boy Scout who carried the Blue Star Flag in memory of Gene. We salute Ensign Eugene George McGarry, a great American fighter pilot and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes. Please visit us at Cranford86.org for additional pictures on the Eugene McGarry story and other stories of the Cranford 86. “I felt a personal connection to Eugene McGarry’s story, having grown up on Long Island where the Hellcats were manufactured. My first assignment in the U.S. Air Force was to help manage and deliver the E-8C Joint STARS, a ground surveillance and battle management aircraft also developed by Grumman with innovative radar technology. Having recently joined the Cranford 86 project, I asked to take the lead on this story and thank Don and Steve for their assistance.” – Stu Rosenthal

(above) Eugene as he appeared in the 1939 Cranford High School yearbook.

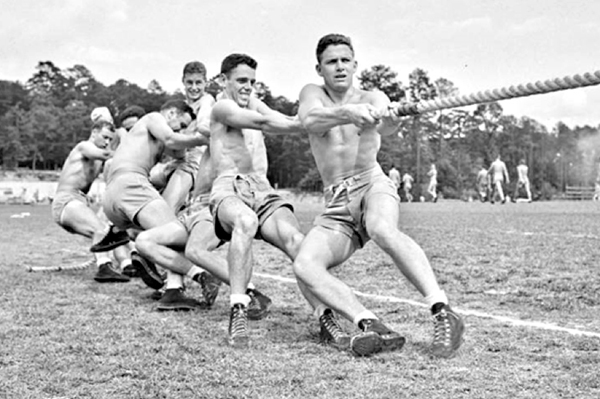

(above) Pre-flight training at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

(above) Pre-flight training at UNC at Chapel Hill. Note the physical condition of the cadets.

(above) Pre-flight training at UNC at Chapel Hill. Preparation for pilots to feel comfortable at 360 degrees.

(above) Pre-flight training at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Simulation of amphibious activity.

(above) Pre–flight training at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill put cadets through a 3 month program that would qualify men for primary flight school. Several top American Universities were used in this manner. The all-in mentality of our nation joined industry, education and personal sacrifice for the common goal of victory.

(above) The overpowered 2000 HP 18 cylinder Grumman F6F-5N Hellcat, the most advanced air to air fighter of its time in 1943-1945. With bullet resistant windshields and self-sealing fuel tank, it was designed to take a hit and still return home. Note the radar antenna mounted on the right wing. Many were armed with six 1/2” machine guns and twin 20 mm cannons. With a record breaking kill ratio of 19:1 it proved to be the most successful fighter aircraft in naval history. 12,275 were manufactured in total, incredibly 11,000 in a 2 year period.

(above) A snapshot of what the Hellcat pilots saw surrounding them in the cockpit of the . Note the size of the radar screen. Inset on right, the image on the screen a pilot would actually see.

(above) While training in Atlantic City , Gene McGarry was known to make periodic strafe passes over his Cranford home at 408 Manor Ave. He would sometimes wave his wings as he passed from his exceptionally loud Corsair 4FU fighter. The visits ended when neighbors complained to Cranford Police.

(above) The Mitsubishi ‘Zero’ aircraft often challenged by US Navy Hellcat pilots . Formerly the king of battle over the South Pacific. With the “Zeke” being faster, more maneuverable and able to climb higher than any allied aircraft at the beginning of the war, it became the motivation of Grumman Aviation Engineering in their designing of the Hellcat F6F.

(above) F6F Hellcats returning to an Aircraft carrier in the south Pacific. Note the ability to fold the wings and store the aircrafts below deck by use of hydraulic elevators.

(above) An F6F Hellcat being tucked below deck on an aircraft carrier by elevator.

(above) The Naval golden wings proudly worn by Eugene McGarry after 2 long years of grueling training . He never wore them in battle, dying in a training exercise off Hawaii weeks before he likely would have entered combat in the So. Pacific.

(above) The USS Bennington as it looked in 1945. Inset is how it looked from an approaching aircraft. It gives a perspective of how small a target the pilots had., they only could land on the front half of the carrier.

(above) St. Peter’s Orphan Asylum on Lyon’s Ave. in Newark NJ where Eugene (8) and Walt (13) McGarry resided for a period after their father Walter Sr. died of pneumonia. Their mother Elizabeth married, moved to Cranford and eventually brought the boys there to live.