Meet Technical Sergeant Cecil L. Spittler, One of Cranford’s 86 and 1930’s Pro Baseball Pitching Ace

Co-written and researched by Don Sweeney and Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault, Edited, and researched by Vic Bary

There were 86 men from Cranford that made the ultimate sacrifice, giving their lives while fighting for our freedom. As the author of 34 of these Hometown Hero profiles, I have not failed to note the numerous other sacrifices made by these brave members of our military. The large majority of returning war veterans, except in some cases in the Vietnam War era, were met with parades and overwhelming thanks from an appreciative, welcoming American population. Most all American veterans took advantage of special educational and loan programs that paved their way to become comfortable in American society. Most found love and created a family and found themselves engulfed in their version of the American dream. This was something that our Cranford 86 heroes gave up along with their life.

As I prepared to tell the life story of Cecil Spittler, while gathering facts from old news clippings, the lyrics of the 1984 Bruce Springsteen song Glory Days were on my mind constantly. The song tells of a high school baseball pitcher, known for his blazing “speedball”. He lives on his own legends which get told and retold at get-togethers with his old friends. So many of the life stories that we have shared to date have been of Cranford young men that were lucky enough to be gifted with talents, early in their lives, that put them up on an athletic pedestal. But their right to relive those “Glory Days” moments, as they aged into their senior years, was stolen from them. The first name that comes to mind is Ray Ashnault, a Little League slugger, known to hit the long ball in clutch situations. Also, Thomas Truxtun was a West Point Lacrosse star, so good that the US Military Academy’s lacrosse field house now bears his name. Archibald Cameron was an All-American football star at Virginia Polytech Institute. Augie D’Alessandris starred at basketball and baseball throughout all four years at CHS at the highest level. Even Dick Borrell made his fame with one catch, in a clutch, game-winning, miracle reception against football rival Roselle High School. Each one’s moment in the sporting spotlight was different, but for every one, they were possibly the greatest accomplishments of their short life. Cecil Spittler took his starring moments farther than any other Cranford 86 hero, achieving legitimate stardom in a big ballpark. But, like all of these sports stars in our Cranford 86, the time that Cecil was given to recount those “Glory Days” moments was cut way too short.

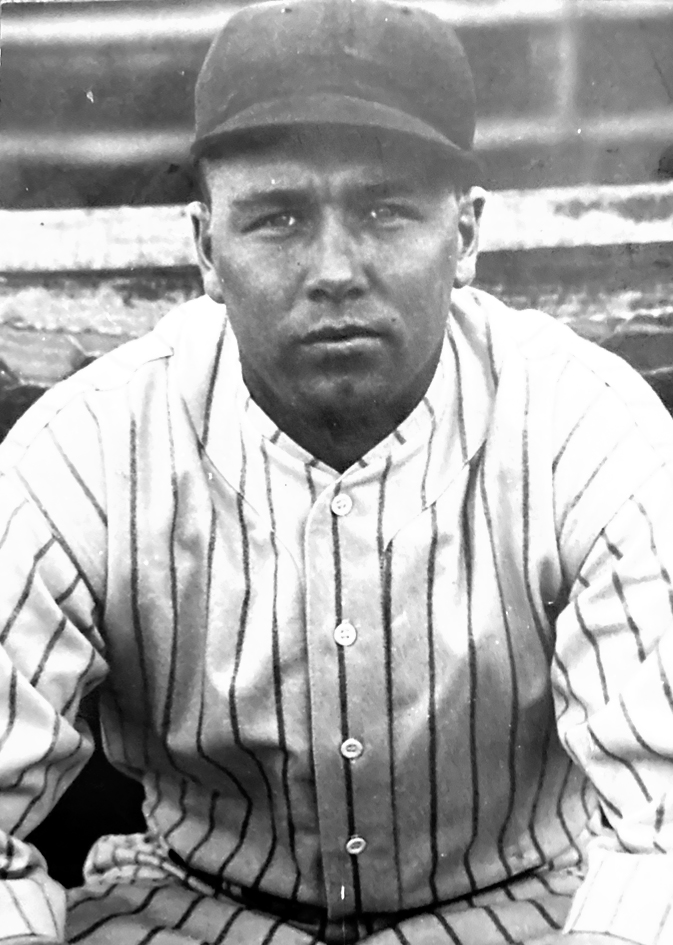

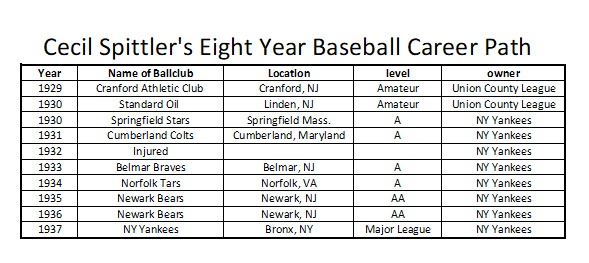

Cecil Spittler, like many young boys, dreamed of reaching the major leagues of professional baseball. The story of his climb is full of triumphs and setbacks, but in the end, looking back, he had quite a ride. Born on April 15, 1911 in the coal mining town of Madera, Pennsylvania, Cecil was one of six children born to Calvin and Nora Spittler. He was praised early on as a gifted mathematician and a high school teacher was quoted to say, “Cecil works algebra like he swallowed the book”. In a biography found at the Cranford Historical Society, Cecil was praised for his dedication to God throughout his early life in Pennsylvania. It was said that Cecil would sooner miss breakfast than miss Sunday school. His family encouraged him to make math his profession, head off to college and settle down to a teaching career. But Cecil had a dream, accompanied with incredible talent, his life’s plan would include a fast moving baseball and a pinstriped uniform. Cecil shined on the baseball diamond throughout Little League and high school. He was called a “world beater” for his incredible talent as a “hurler” with a fast ball that became known as the “Spittler Fireball”. During the seemingly never-ending long winters, Cecil and his best friend were known to dig out a pitcher’s mound and a batter’s box in the deep snow, so they could start their baseball season before the anticipated thaw. In 1928 he graduated from Philipsburg High in Pennsylvania, just one year before the crash of the stock market which marked the beginning of the Great Depression. Cecil’s sister Hilda was able to find employment in the bustling commercial area of Bayway, between Linden and Elizabeth, New Jersey, where blue collar jobs were still available. Cecil soon followed and was employed as a surveyor’s helper at Standard Oil. Union County had a well-organized amateur baseball league and Cecil wasted no time in joining, first as a member of the Cranford Athletic Club in 1929. As part of the Standard Oil team, his natural talent to throw faster than anyone ever known in the Union County leagues, drew attention in local newspapers. He was soon offered a deal with the Springfield Stars in 1930. A clipping from the family scrapbook told of a bold and impetuous move made by the talented nineteen-year-old. Cecil drove from his Linden home to Philadelphia to meet Cornelius McGillicuddy. Known to the baseball community as Connie Mack, McGillicuddy was the owner of the Philadelphia Athletics for 50 seasons. Cecil asked Mr. Mack for the opportunity to demonstrate his skills with a baseball. As Connie Mack was known to do, he led young Spittler to Shiba Park and let the ambitious young Jersey kid show him what he had. After the workout, Mr. Mack told Cecil that he had what it takes to be a pitcher in the big leagues, but candidly stated that without a curve ball, he wouldn’t get anywhere. Cecil took Connie Mack’s constructive criticism to heart, and within a year he had added a curveball to his repertoire.

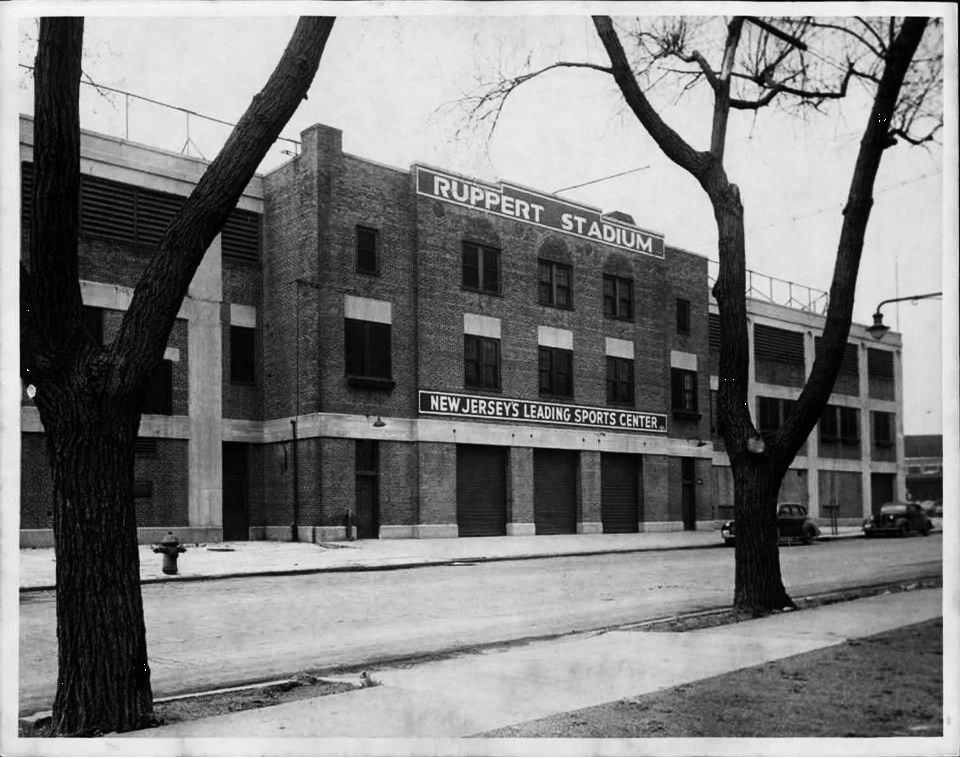

A little background of the baseball business in the 1920s and ‘30s might help you to imagine what is about to happen in our hero’s life for the next eight years. Baseball was coming off an amazing boom period throughout the Roaring ‘20s. The New York Yankees’ owner was Jacob Ruppert, a German immigrant and owner of the 30 million dollar Manhattan brewery that crafted Knickerbocker Beer. Ruppert not only built an empire in major league baseball, but he created the supporting minor league program as well. Several A and AA minor league teams from up and down the east coast were acquired by Ruppert which created a steady flow of young talent to fuel his New York Yankees organization. He purchased the Newark Bears and made them the AA gem (the highest level) of his minor league system. It makes me wonder if the ability to sell beer to his baseball fans had anything to do with his master plan. With air travel still in its infancy, the Bears’ proximity to New York allowed for easy access to his stable of talented rising stars just across the Hudson River. In this era, Major League Baseball was played exclusively during daylight hours and was viewed only in stadiums by live audiences. Although the technology to broadcast by radio and eventually television was available, owners feared that giving their games away for free could possibly destroy their financial empires. Owners like Ruppert eventually realized the lucrative possibilities of paid advertising through mass media that up until then had not been considered. The Depression affected the revenue of Major League Baseball teams, but the business of baseball still did relatively well during those 12 years, possibly because it offered a temporary diversion from the troubles of the day. The average professional American baseball player of the era was considered a superstar and paid about $4,500.00 per season, equal to about $70,000 in today’s money. Ninety-five percent of the revenue came from attendance at stadiums which charged about $1.00 for admission and .50 for bleacher seats.

As in the past, our stories come to life with the results of the hard work done by our researchers and our ability to locate a family member. The Cecil Spittler project was blessed by both. Our long-time supporter Mike Sapara, who inspired story number one featuring his classmates Ray Ashnault and Joe Minnock, informed us that his girlfriend, Darla Canney, was the niece of Cecil Spittler. Darla’s mom was Betty Jean, Cecil’s sister. A treasure chest of information, assembled in a classic scrapbook, was delivered to me. News clippings from the sports pages and correspondence to and from the battlegrounds of Europe helped us to piece together the baseball career of Cecil Spittler, from Little League to the New York Yankees as well as his Army life overseas. It was a privilege to read the colorful words of the talented sportswriters of the day. Their reporting was the only way that fans, who were not in attendance at the ballpark on game day, were informed of the day’s action of America’s favorite pastime.

Between the years 1931 and 1938, young Cecil Spittler was on a wild ride, which several times brought him tantalizingly close to the pitcher’s mound on the field in “The House That Ruth Built”. In 1931 Cecil was signed by a New York Yankee minor league “A” team, his first paying job in the sport that he loved. In 1932, he impressed onlookers with the Springfield Ponies in the Lackawanna league in Massachusetts, with an 11-1 record. It was here that he received professional training and displayed his ability to learn quickly. Cecil had now perfected his powerful curve ball and had added a hook pitch to his skillset, which brought his craft to the next level. His ability to perform under extreme pressure was soon noted by his coaches and local sports reporters. Even when found in difficult situations by the mishandling of balls behind him, he cast no blame and just bared down and became even more relentless with his throwing. He was described to possess “baseball gruff”. In late 1932 “Ceece” as he was now called, was sent to the Newark Bears, the Yankees AA team. Young Cecil, now only 21 years old was on the fast track towards becoming a New York Yankee. But as quickly as his throwing abilities had advanced his career, they now stalled it, and he ended up demoted back to “A” level ball, for what was described in a sports page article as “not measuring up to requirements”.

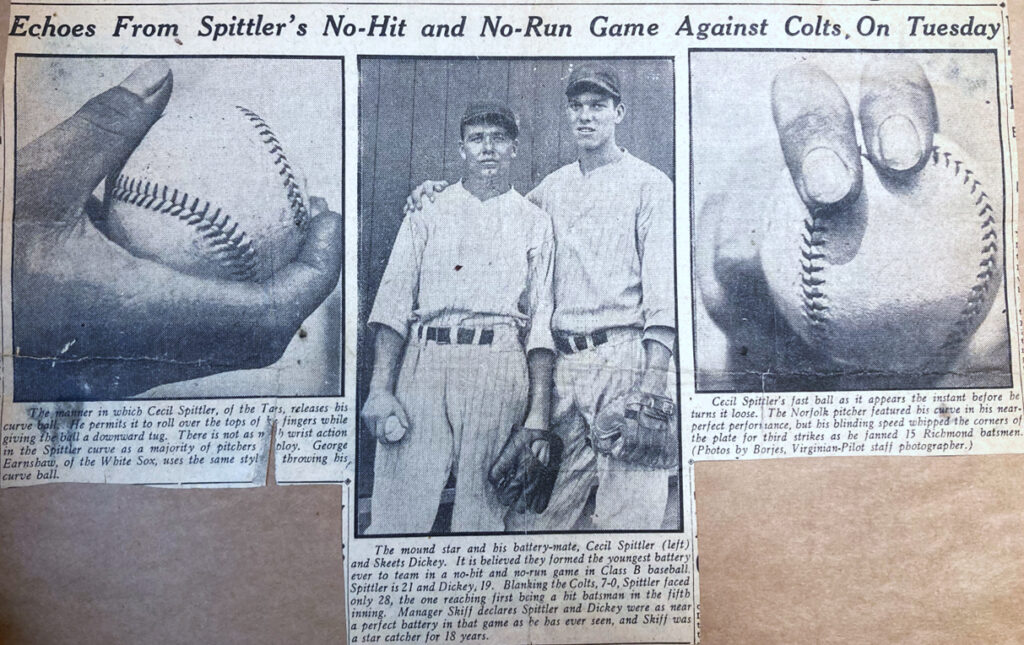

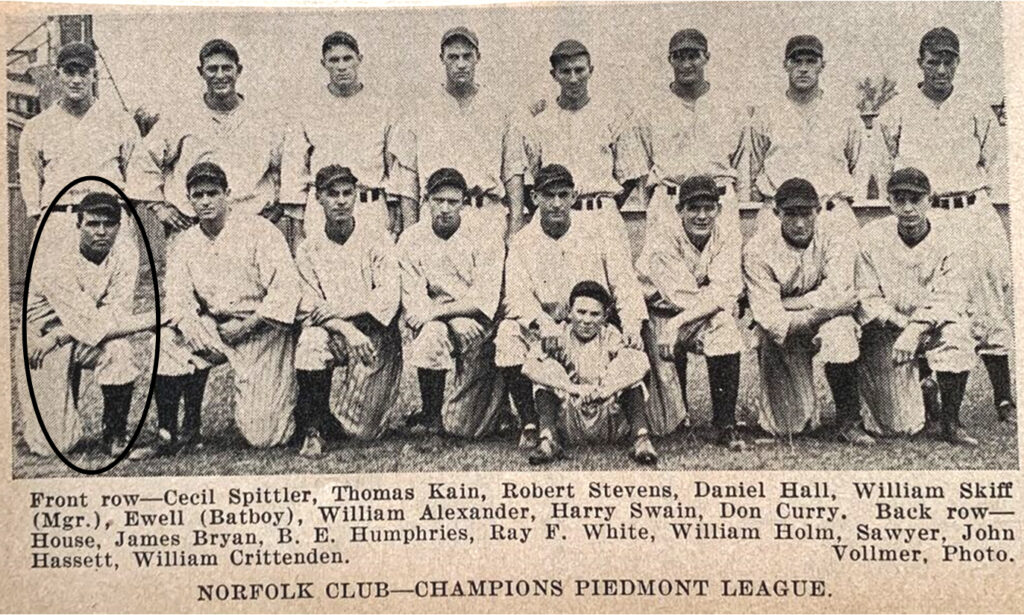

Following the 1933 season, a star Yankee pitcher, Russell Van Atta, played a promotional tour throughout New Jersey to raise awareness of baseball. He chose Cecil to join the all-star team. Van Atta opened the game with a dazzling pitching display where he went four innings not giving up a hit. He then handed the ball to our Cecil, and everyone in attendance was shown what a former Newark Bear’s pitcher could do. Cecil completed the last five innings without allowing any hits, yes, a nine inning no-hitter, a very rare occurrence, even in 1933. At one point he struck out eight in a row. Van Atta reported back to his Yankee contacts that Spittler should be reconsidered in the hierarchy of the Yankee minors. So, for the ’34 season, he was sent to Norfolk, Virginia to join the Tars and work under a legendary manager, Bill Skiff. On July 24th, against the Richmond Colts, Cecil, renewed with confidence and swagger, pitched another no-hit event, this time from inning one to nine. If not for the batter who reportedly didn’t get out of the way of an inside “Spittler Fireball” that clipped his elbow, not one of the Colts would have reached first base. Twenty-nine batters faced, twenty-eight retired, one short of the elusive perfect game, Cecil struck out fifteen. The Tars, led by Cecil Spittler, went on to win their first championship pennant in fifteen years. Cecil’s performance that season was rewarded with a call back to the Newark Bears. On September 30th, Cecil was honored by the mayor of Linden, Myles McManus, who was his biggest fan. For pitching a nearly perfect game and his promotion back to the Newark Bears, a dinner was held at the Linwood Tavern on South Wood Avenue, still a community hot spot. Cecil was awarded an engraved wristwatch and over one hundred were in attendance, including some Yankee ballplayers.

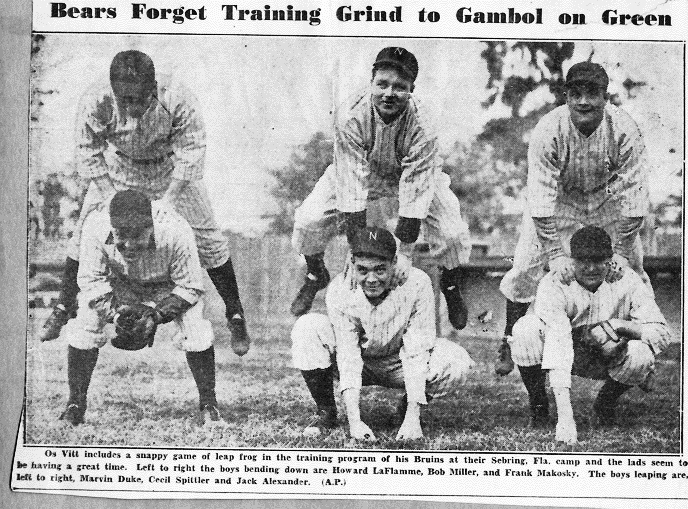

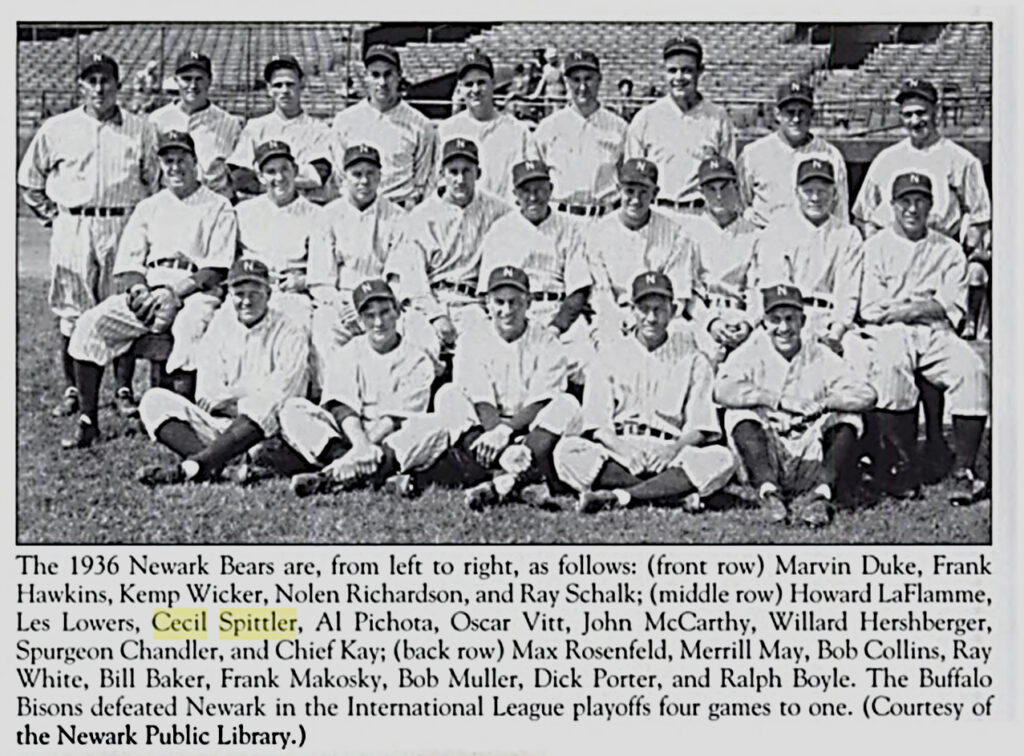

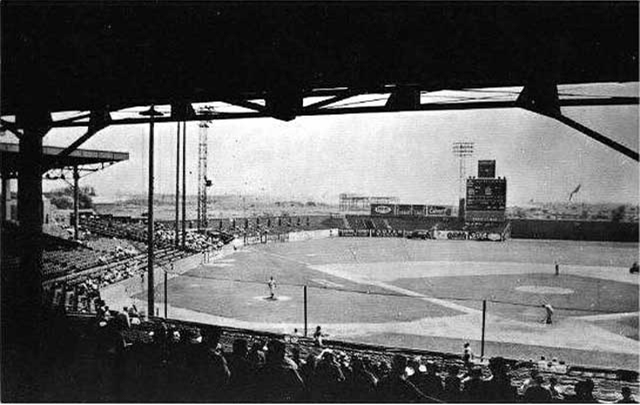

After Spring training in Florida, Cecil was selected to start in the 1935 season opener. In a double-header at the Bears’ Ruppert Stadium in the Ironbound section of Newark, Cecil watched as the Bears lost the first game. But as the starting pitcher in the second game, Cecil gave a stunning performance, producing a 3-0 victory. His control was described as perfect. Cecil Spittler appeared in forty-five games that season and had a record of 14-10 with an ERA of 4.03. The local sports writers were thrilled with the “sandlot” hero. With most up-and-coming stars recruited from college programs, Cecil was said to have a B.S.L. (Bachelor of Sandlot). The Bears’ manager, Otto Vit, referring to Cecil’s unconventional pitching form, said “He does everything wrong, but he wins”.

The 1936 season started off with a big contract signing for Cecil that made headlines. While no dollar amount was disclosed, it was reported that “the Bears’ ace was rewarded handsomely for his stellar performances in 1935”. It seemed that now, it was just a question of when, not if, he would be moving up to the Yankees. Seemingly, the biggest obstacle in Cecil’s path was the talent-heavy Yankee roster that would need to make room for another superstar. The Bronx Bombers would win the World Series in 1936 as they did in 1937, ‘38 and ‘39. And so loaded with talent themselves, it was said that the Newark Bears, not the World Series losers New York Giants, were the second best team in baseball in 1936.

At this point, Cecil’s career seemed to be on the upswing. However, we discovered that he was having severe pain in his throwing arm which he was slow to report to management. He could still pitch, but not to the level that AA baseball required or as dominantly as he did in the 1935 season. Cecil was sent to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for an advanced diagnosis, which was a sign that Mr. Ruppert saw value in Spittler’s future with the Yankee organization. It was determined that he had a severely separated muscle in his shoulder. A Brooklyn surgeon promised success and performed a procedure that would remove the damaged tissue and return the six foot, one hundred eighty-five pound, right-hander to his former self. After surgery, Cecil was sent back to Union County to rest and slowly work his arm back to strength. Sportswriters who asked Cecil how his arm was doing would receive extremely promising responses. But, a couple performances in public in the Union County league, would display lackluster results that left Spittler in need of lengthy recovery time after each appearance. There was also some talk of a mental element to his demise, as well. The Yankees were still of the mind that Cecil would work his problems out, so he was removed from the Bears’ injured reserve list, and he was signed as a probationary pitcher for the New York Yankees. This was seemingly a place to hold him under contract, safe from another squad’s acquisition, while he healed. Cecil remained in that position until 1938, when his baseball career ended after his arm did not recover as was hoped. Sadly, Cecil never was able to pitch a game in Ruppert’s Yankee Stadium.

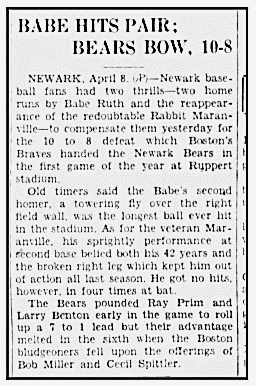

In the Spittler family memoirs, there is a baseball, encased in plastic, and labeled as the ball that their Uncle Cecil used to strike out Babe Ruth. At first, we found that to be impossible, because Ruth retired in 1936 and Spittler had not made it to the Yankees until 1937. However, in our research we learned of a promotional pre-season game at Ruppert Stadium in 1936. The major league, Boston Braves would play the powerful Newark Bears, in an exhibition game which was commonplace in the day. The sports pages were on fire with anticipation, as the Boston Braves had just acquired Babe Ruth, the biggest box office draw of the last decade. The headlines were bold, Cecil Spittler, the ace of the Newark Bears, would face Babe Ruth. Family and friends must have been elated for Cecil. When game day arrived, surprisingly, Cecil was not the starting pitcher, surely a disappointment to Cecil’s local following, but Babe Ruth did not disappoint. On his first at bat, he crushed a pitch over the fence as he had done over 700 times before. Then, later in the game, he hit the longest home run in Ruppert Stadium history. The Bears had an early 7-1 lead when Cecil and Bob Miller were brought in for the save, which was not to be. They gave up nine runs collectively, the final score was Braves 10, Bears 8. It was not reported as to which pitcher took the loss, but Cecil was the last pitcher mentioned in the article. We speculated that it was Cecil’s recently revealed arm injury which negatively affected his performance that day. He may have been put in the game, just to allow him to face the Babe, as the previous day’s headlines had touted. So, it is feasible that Cecil Spittler did face Babe Ruth, and possibly struck him out. To date, we have not found any written evidence to support this, but as we have learned, it is best to believe in the family legends when any doubt is present.

After voluntarily leaving professional baseball, Cecil returned to the Bayway area. He worked in Linden as a shipping clerk at the chemical company, American Cyanamid, and lived in Cranford at 15 North Avenue with his parents. We could find no further details about Cecil’s transition back to life off the pitcher’s mound, until we learned that he was drafted in November of 1942, at the age of 31, eleven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Cecil was shipped to Camp Maxey in eastern Texas to train with the 102nd Infantry Division, 407th Infantry Regiment or “Ozarks” as they had been known since WWI. As the unit slowly assembled and grew to their projected size of 40,000 men, they were already being specially trained for the encounters that were likely to occur. The Normandy invasion and anticipated march across France were still more than a year away, but General Eisenhower had incredible foresight. He knew that when the Nazis, these attackers who had occupied nearly thirty countries, were forced back to their homeland, they would defend it with incredible ferocity. At Camp Maxey, the Texas terrain mimicked the European landscapes that the Army was preparing to attack. There were recreated German villages, with mock snipers posed in windows, a scenario that foretold what lay ahead for our Hometown Hero.

From Camp Maxey, the 102nd was moved to Camp Swift, also in Texas, for tactical training with tanks and helicopters. In total, 90,000 soldiers were training at Camp Swift for the upcoming attack of the German homeland. Cecil Spittler, already at the rank of sergeant, served 6 months there as an instructor. From Texas, the training moved to Louisiana for advanced maneuvers instruction. At the conclusion of this intense battle training, the 102nd Infantry Division was staged at Fort Dix in New Jersey, as they awaited orders to start their mission. Letters from the family scrapbook tell of Cecil’s elation at being able to reach home by train and bus, in just a few hours, to spend some time with his family and girlfriend Ruth Hodges. Ruth was a nurse at Elizabeth General Hospital, she and Cecil married on August 19, 1943. With the great need for nurses in the military, after Cecil was deployed, Ruth answered the call of duty herself and enlisted in the Navy as an ensign. Spittler’s 102nd Infantry Division landed in France, at Cherbourg, on September 23rd, 1944, just east of the Normandy beaches. They completed their training in nearby Valognes, after which they traveled approximately 400 miles, unobstructed, across the recently liberated French countryside.

A high-level understanding of what was then occurring in the European Theater of Operations may be of help to our readers at this point. General Eisenhower had implemented a broad attack strategy. Several armies, each of approximately 100,000 soldiers, fanned out across France. They were methodically liberating towns and villages while advancing to the Rhine River, the natural border between Germany and several other European countries. When each army was poised at the Rhine, a massive invasion into Germany would be conducted. In total, this surge would include about 2 million Allied soldiers. Through the stories that we have told so far, our regular Cranford 86 readers may be familiar with the troop movement that was occurring during this time. In the far west of France, we traveled with Private Bill Hinkle in his trek across the Vosges mountains and the Maginot Line with the 7th Army. We learned how Arthur Galvin in Patton’s 3rd Army struggled with supply line shortages as they worked their way through central France. And now we follow Cecil Spittler, a member of the 9th Army. From the eastern French countryside, under the command of General Simpson, Cecil would be led into violent encounters while breaking through the Siegfried Line at the Hurtgen Forest and then onto the Roer River region. With General Eisenhower as its mastermind, Europe had become an enormous chess game.

In 2018, I had the honor of interviewing for TV 35, our town’s oldest living WWII hero, Peter Klein. Sadly, Peter passed away this year. We will miss him and the valuable historical input that he provided to the Cranford 86 effort. His description of the Hurtgen Forest in the wicked weather of 1944 gave me an understanding of what Cecil and his unit were experiencing. Peter had landed at Normandy Beach, fought in the Battle of the Bulge as well as in the Battle of Hurtgen Forest. He told me that the Hurtgen Forest, which was on the border between Belgium and Germany, was the roughest for him. He told me it was the coldest he had ever been in his life. The snow was deep, and the weather was brutal. Peter said that they were totally underdressed, and he hadn’t even been issued a winter coat. The Longest Battle: September 1944 to February 1945 – from Aachen to the Roer and Across, by Harry Yeide, is a fantastic book that we used in our research. It helped to guide us through the first combat, two months long, that Cecil’s unit encountered in early October inside the Hurtgen Forest. It stated that the snow gear didn’t arrive until January of 1945. Like Peter Klein, Spittler too may have been underdressed for that same bitter winter. Reading the details of war, where thousands of soldiers traversed the Siegfried Line, supported by hundreds of tanks and 2,500 aircraft, was heart-pounding. The swiftly moving Roer River lay before them, and with its many bridges it began a historic challenge for the 9th Army. For the next months, advances were said to be measured in feet not miles, with the same land being fought over several times.

In late 1944, many felt that the mighty Panzer battalions, whose disabled tanks covered the roadsides, had been taken out of action and the Nazis were near collapse. Rumors were spreading wildly through the Allied troops which created false hopes that the war would be over by Christmas. The actual truth, which was well known to General Eisenhower, was that the German forces from Normandy, had retreated to the German and Belgian borders. They had repaired and refortified the Panzer tank divisions and had now concentrated their might with many reinforcements into a Schwerpunkt strategy, a military concentration of sorts. This industrial manufacturing region was crucial to the Nazi war efforts and Hitler’s orders were clear. There would be no surrender and they were to fight to the death. In order for the 9th Army to reach the Rhine River to join the other forces for the assault on Germany, they would have to conquer the Roer River industrial region. The 9th Army of over 100,000 soldiers was under the control of General William Simpson, probably the most successful and most unknown general of the era, who served with distinction in both WWI and WWII. The flamboyant styles of Generals Patton, Bradley and British General Montgomery stole all the headlines during this period, as General Simpson quietly completed his wartime tasks flawlessly, including victory in the Roer River campaign, which was the longest and fiercest of the war.

Vic Bary, our military expert, took the lead on research for the combat actions of Sergeant Spittler. He discovered that Cecil’s unit was on a mission to attack three bridges that cross the Roer River into four small, Belgian villages, Welz, Linnich, Roerdorf and Flossorf, a mile or two separated them from each other. The area was being protected by the 304th Volksgrenadier Division, a new creation of the German Army, after its horrible defeat in Normandy. A Volksgrenadier contained more automatic weapons and short range munitions than an ordinary infantry unit. They were often paired with an SS Panzer Tank Division, as was the case in this instance. The houses in the villages were full of snipers, and Allied advances across the river bridges were plagued by booby traps and mines that the Germans had planted on streets and in houses. All of this added up to an extremely treacherous mission. (See the YouTube videos in our online story at Cranford86.org) Technical Sergeant Cecil Spittler was with the 407th Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion, Company B. A typical company had about 150 -175 men and was broken into rifle platoons of about 40 each. Cecil now a Tech. Sergeant (E-7), was second in command of his platoon, under a 2nd Lieutenant. Two letters written by Cecil indicated his whereabouts at this time. One was written on November 27th, while in a small town in Holland. Cecil wrote that he was in a foxhole just fifty yards from a German pillbox that was putting out heavy mortar fire. One shell had even lodged itself into the top of his foxhole. In another dated November 28th, he told of being tucked into a basement as he awaited the start of “another offensive push”. Our research shows that rifle platoons were being sent across the river to neutralize the sniper fire which had been causing many Allied casualties. We believe that on November 30th, 1944, in the village of Welz, Cecil was on one of these missions. It was here that he lost his life, just two days after writing those letters home.

The battle for the Roer lasted six months and sadly, the last four months were without the services of Tech. Sergeant Cecil Spittler. The 102nd Infantry Division would continue through Germany until that country’s surrender in April 1945. The 102nd, that started in Cherbourg in September with about 100,000 soldiers, reported their casualties as follows: 932 killed in action, 3,668 wounded, 185 missing, and 137 taken as prisoners of war. The Germans had suffered considerably more.

At pivotal moments in many of our stories, the thought always seems to come to mind as to where our hero was at this time. I couldn’t help but wonder if the accurate arm and “ability to perform under extreme pressure” of our former Yankee pitcher had ever been asked to perform in battle. We’ve all seen WWII movies when a hand grenade needed to be thrown into a pillbox or through a second floor window. I can just imagine the commanding officer calling on Sergeant Spittler to deliver the perfect strike on demand, taking out an enemy position or sniper’s nest. What a moment that would have been. When Cecil had some downtime, in the barracks, on a transport plane, or huddled in a foxhole or basement, we picture him surrounded by wide-eyed, younger, comrades-in-arms. He was one of the few who had a chance to achieve a touch of greatness, before making the ultimate sacrifice. We hope that he got great joy out of regaling audiences with tales of his “Glory Days” on the baseball field, just as described in the Springsteen song.

Technical Sergeant Cecil L. Spittler was buried in the beautiful Netherlands Military Cemetery in Margraten, before being brought home on April 14th, 1946. When he was laid to his final resting place in Clover Leaf Memorial Park in Woodbridge, he received a full military funeral hosted by the Captain Newell Rodney Fiske VFW Post #335 of Cranford and the Cranford American Legion Post #212. Cecil was survived by his wife, Ensign Ruth Hodges Spittler, his parents Nora and Calvin, three sisters and a brother.

We’d like to thank Vietnam veteran Mike Sapara, for sponsoring the banner of Cecil Spittler which will be unveiled on Memorial Day, 2023. This year’s ceremony to honor the Cranford 86 will highlight Technical Sergeant Spittler, who sacrificed his life safeguarding freedom, allowing the privilege that is our way of life to continue for every American. We love hearing comments from our readers, let us know what you think of our ongoing project, email us at info@cranford86.org and follow us on Facebook at Cranford86.

Additional Links

https://www.abmc.gov/Netherlands Tribute at American Cemetery in Netherlands

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lq-2DzcY9JE Youtube ling film of the Roer River crossings in Julich