Sergeant First Class Gilbert A. Secor receiving his Silver Star. America’s 3rd highest medal for bravery for his actions at Lang Vei.

Meet Master Sergeant Gilbert A. Secor, Green Beret. One of The Cranford 86.

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal

and military proofreading by Jim D’Arcy.

Sergeant First Class Gilbert Secor posing with a platoon of Chinese Nung soldiers, they had the reputation as the most feared fighters of all the minority groups trained by the Americans.

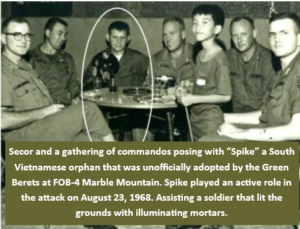

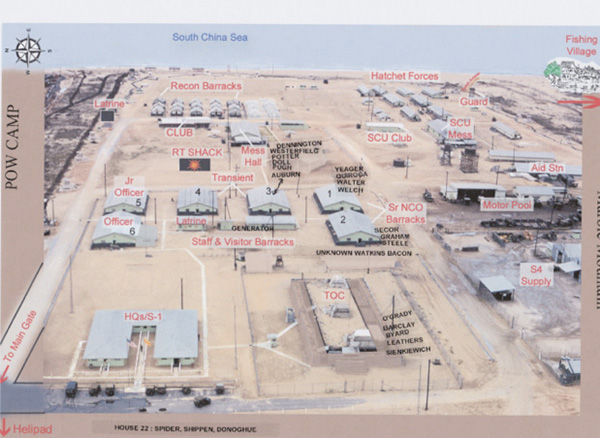

It was just after midnight on a dark moonless August 23rd, 1968, at Forward Operating Base #4 Command and Control North (FOB4-CCN) At Marble Mountain near Danang Airbase, South Vietnam. An unusual gathering of an estimated 100 Green Beret special forces was taking place for a promotion board. While Green Berets are famous for their survival skills in the jungles and rough country side, living off the land and being constantly on guard, tonight they were letting off some steam as they were in the secure surroundings of their home camp. It was reported that the soldiers were drinking heavy, swapping war stories and toasting lost comrades into the early morning hours. It was a well-deserved break from the life-threatening existence that they endured on most days of duty.

The FOB was surrounded on three sides by fortified fences and at their rear was a 300-yard beach to the China Sea. A sharply barbed concertina wire fence about 50 yards from the water’s edge protected the rear entrance to the base. While there were reports of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) activity in the area, a Security Team (ST) was sent up to the peaks on Marble Mountain as a look out. No sightings were reported, the men felt safe and secure for the night. Little did they know that all hell was about to break loose.

The metal emblem shield of The MACV-SOG at FOB-4 that was recovered after the August 23rd 1968 attack. It was dented from small arms fire, shrapnel and flying debris. Paul Christensen inscribed his best friend’s name on the back as a memorial that he kept until his death.

With most partiers turned in for the night, a silent procession of sappers, North Vietnamese special force warriors, started crawling slowly up the beach towards the wire perimeter. In waves of 12 they gathered on the sandy perimeter until they numbered close to 100. They carried woven baskets full of hand grenades and larger more powerful 5 lb. satchel charges that could make tooth picks out of the camp’s flimsy plywood hooch’s (buildings). Over their shoulders hung the infamous Russian made AK-47 rifles. Sappers were Hanoi’s most elite commandos. Their missions were of a suicidal nature. They dressed in only white loin cloths or khaki shorts. Their heads were wrapped in rag headbands with words written in blood that said, “we came here to die”. Their bare chests and limbs were greased to allow squeezing through tight passage ways and fences. No doubt they were a well prepared and trained fighting force.

Mortar fire soon began from NVA above on Marble Mountain that illuminated the FOB and was an obvious signal to the sappers to begin their onslaught. By 02:30, the two South Vietnamese sentinels were killed, and the well-planned surprise attack began. With our Green Beret troops either in deep sleep or slow from the “many screwdrivers” that were still being consumed by some, the first few minutes yielded many casualties. The security team up on Marble Mountain quickly eliminated the mortar fire from above but could do little to stop the slaughter that was about to besiege the large gathering of “America’s best”.

A book located from our research sources “Secret Commandos: Behind enemy lines with the Elite Warriors of SOG” and The Sentinel, a military publication, held detailed reports of the three-hour intense hand to hand battle. Amazingly nearly every encounter that took a special serviceman’s life was documented. One of these Green Beret soldiers that lost his life that morning was Cranford’s own Sergeant First Class Gilbert Secor, a 36-year-old, 18-year veteran, on his fourth tour of duty in Vietnam. In a memoir written by Secor’s best friend Paul Chistensen and told by his son, Secor called to Christensen. “Paul, look out we’re under attack!”. Christensen and Secor, both combat medics had been together in Vietnam since 1962. Sergeant Secor saw sappers about to enter a complex of supply buildings with munitions wrapped around their bodies. There were reportedly a million dollars’ worth of munitions and supplies in those supply buildings. Secor knew he had to defend that site. He ran to the wall of the munition storage house just as the charges were detonated by the invaders. The pressurized torpedo shaped acetylene and oxygen tanks inside began exploding and shooting across the ground like rockets. Unexpectedly the wall that Secor was taking cover behind was blown off its foundation and crashed down upon him. A comrade ran to him immediately, but it was too late for our Cranford hero.

A book located from our research sources “Secret Commandos: Behind enemy lines with the Elite Warriors of SOG” and The Sentinel, a military publication, held detailed reports of the three-hour intense hand to hand battle. Amazingly nearly every encounter that took a special serviceman’s life was documented. One of these Green Beret soldiers that lost his life that morning was Cranford’s own Sergeant First Class Gilbert Secor, a 36-year-old, 18-year veteran, on his fourth tour of duty in Vietnam. In a memoir written by Secor’s best friend Paul Chistensen and told by his son, Secor called to Christensen. “Paul, look out we’re under attack!”. Christensen and Secor, both combat medics had been together in Vietnam since 1962. Sergeant Secor saw sappers about to enter a complex of supply buildings with munitions wrapped around their bodies. There were reportedly a million dollars’ worth of munitions and supplies in those supply buildings. Secor knew he had to defend that site. He ran to the wall of the munition storage house just as the charges were detonated by the invaders. The pressurized torpedo shaped acetylene and oxygen tanks inside began exploding and shooting across the ground like rockets. Unexpectedly the wall that Secor was taking cover behind was blown off its foundation and crashed down upon him. A comrade ran to him immediately, but it was too late for our Cranford hero.

The badly damaged Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) barracks hooch that Gilbert Secor shared with Ray Steele and Cleveland Graham at Marble Mountain on Aug.23, 1968.

When the light of dawn came upon the camp, sappers were still running around the carnage as the Americans slowly took back control of the FOB. Sixteen American Green Beret soldiers were killed, the most in the history of these legendary fighting men and 48 were wounded. Dozens of South Vietnamese soldiers died as well. Thirty-eight sappers laid dead across the camp. It was later found that a Vietnamese kitchen helper acted as an informant to the sappers, which explained the precise accuracy and timing of the attack.

Chief of Special Operations Group (SOG) Colonel Cavanaugh arrived in the morning to assess the damage and came upon a detail carrying away Sergeant First Class Secor’s body. He recalled not a year earlier Secor being in his office requesting an additional fourth tour in Vietnam. He unfortunately granted his fatal request.

While the battle of 23 August 1968 at FOB-4 Danang was obviously Secor’s last battle, his career as a soldier was a long storied one. Secor entered the Army in 1950 at 18 years of age during the Korean War. The details of Sergeant Secor’s military career from the early years was not available to us by our deadline, as much were top secret and classified due to the clandestine nature of The Special Forces. However, the medals he received for merit and heroism stand as proof of stellar service to his country.

We were able to uncover the actual military report that was declassified in 1992 of the dynamic rescues of 9 trapped Green Berets from an underground Tactical Operations Command (TOC). It was here that Sergeant Secor’s actions earned him the army’s third highest award for heroism, The Silver Star. We were also able to obtain the letter that accompanied the medal detailing the actions that happened that day February 7, 1968. Just six months before the battle that took his life.

We were able to uncover the actual military report that was declassified in 1992 of the dynamic rescues of 9 trapped Green Berets from an underground Tactical Operations Command (TOC). It was here that Sergeant Secor’s actions earned him the army’s third highest award for heroism, The Silver Star. We were also able to obtain the letter that accompanied the medal detailing the actions that happened that day February 7, 1968. Just six months before the battle that took his life.

Lang Vei was a Green Beret camp on the border between Laos, and the company headquarters at Khe Sanh. The famous TET offensive, NVA’s largest action in the entire war was pushing our troops abilities to their limits. Lang Vei had been overrun by an enemy battalion using 11 Russian made tanks with 76 mm canons. Up until this point the NVA had never used tanks. American forces had some lightweight M-72 anti-tank rockets that had never been tested and failed in their first test here. The group of 9 Green Berets along with some high-ranking South Vietnamese soldiers were trapped underground in the TOC bunker with NVA troops dropping a variety of explosives into the bunker air vents and down the bunker stairs trying to wipe them out. The bunkered underground command center had radio communication with the Khe Sanh headquarters 5 KM away, but their request for rescue was denied due to the risky nature of their situation and the fact that the headquarters at Khe Sanh was under heavy assault at the same time.

The Green Berets at Lang Vei decided to fight their way out of the bunker in a blaze of glory rather than be captured and tortured or killed. When their Green Beret counterparts at Khe Sanh heard of their suicide mission plans, an alternate plan was devised. It was an expertly crafted diversion tactic using U.S. fighter jets. Two strafing runs were made with bombs and machine guns blaring, causing the NVA to take cover. The next two runs were visually as aggressive but without munitions keeping the enemy at bay. When the 9 trapped Green Berets heard the third pass commence, they were to make their escape from the bunker and run to awaiting rescue teams. On the forth pass they could hopefully reach the helicopters that were sent from Khe Sanh. Sergeant Secor was one of the fighting medics that was on one of those helicopters. Under heavy fire from AK-47 and rocket propelled grenades, Secor set up a rocket launcher to give cover and diversion that allowed his badly wounded comrades, many being carried, to board the aircrafts and be evacuated to safety. In total 24 Green Berets were involved in the rescue at Lang Vei, 10 were killed, 14 including Secor survived. Sadly, many of the survivors of Lang Vei were killed with Secor on August 23rd, 1968 at Marble Mountain.

Barracks area at FOB-4 Marble Mountain

Due to the top-secret status of Secor’s unit, no publicity of either of these episodes was ever made. The families had no idea of the actions that took their loved ones from them. The Special Force soldiers were instructed to never speak of their mission to anyone, in fact they all signed a secrecy agreement that restricted any comments of their actions for a 20 year period. A simple generic letter, thanking their family’s contribution from a grateful nation was all they received. Medals were not issued after the battle at FOB4, it wasn’t until much later and much lobbying that 24 Bronze Stars with a V for valor were presented, some posthumously. Also, it wasn’t until the 50th anniversary, October 2018, that a formal memorial service was organized in Las Vegas by The Special Operations Association, with 300 people representing 11 families of the sixteen heroes and their surviving Green Berets comrades. Bonnie Cooper, the association’s coordinator, a retired intelligence analyst and an Army special forces wife herself, gave us three email addresses of the breakfast’s attendees that she felt knew Secor. I was honored to be able to interview two of them. After spending so many hours reading the scores of military accounts of these same men in battle, it was like being able to speak to fictional superheroes.

She also provided us with the program and an article published in The Stars and Stripes newspaper that recorded the tears and hugs that were shared between them. A touching multimedia production introducing the faces of the 16 honorees can be seen at Cranford86.org

This passage is from the cover of the 50th Anniversary program of the 23 August 1968 attack.

This was a classified war. Their sons, husbands, fathers, brothers were killed in secret circumstances. They had never gathered in memorial, nor would they learn for many years the heroic details of how young soldiers and combat veterans shook off the stunning attack and fought face-to-face with the enemy that had penetrated their inner sanctum.

This was a classified war. Their sons, husbands, fathers, brothers were killed in secret circumstances. They had never gathered in memorial, nor would they learn for many years the heroic details of how young soldiers and combat veterans shook off the stunning attack and fought face-to-face with the enemy that had penetrated their inner sanctum.

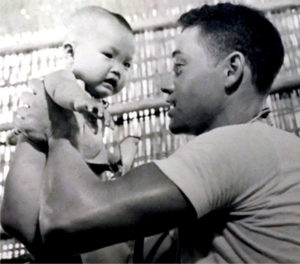

Our Hometown hero, Sergeant First Class Secor, it is so nice to say, had a soft side as well. The Green Berets were known to reach out to the local communities and villages, to befriend the indigenous population. Gifting candy and medical assistance were the most frequent gestures of kindness. In the March 5th, 1962, issue of US News and World Report an article featuring Secor was published about his work with babies in a Vietnam village. The same story was featured on Eyewitness news on television. We requested a copy of that story from Rutgers library, at deadline for publication we had not yet received it. We hope to post it online at Cranford86.org upon its arrival.

While serving in Vietnam Green Berets often administered medical treatment to befriend indigenous village people. Here Sergeant Secor is treating a baby with syphilis.

Barracks

While serving in Germany, Gilbert fell in love and married his wife Margot Baunach in 1957 and had a son named William, who was born at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina in the following year. Margot became a US citizen in 1962 after coming to Cranford where she lived with her son William at the home of Secor’s sister Adelaide Connell at 171 North Lehigh Ave. That address was Gilberts official address while he served his country abroad. After being reunited in Okinawa, Japan the family enjoyed a close relationship while there for three years. Later the Secor family would settle in Fayetteville North Carolina near Ft. Bragg, the US headquarters for American Green Berets. We found William through ancestry.com still living in North Carolina, he was 9 at the time of his father’s death.

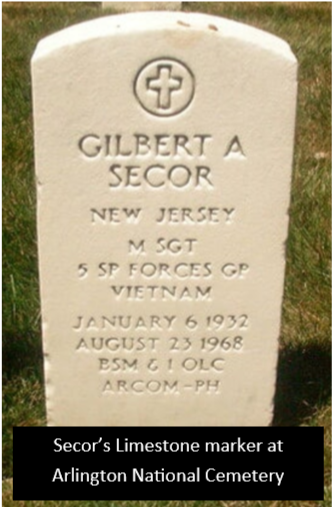

Sergeant First Class Gilbert Secor was promoted posthumously to the rank of Master Sergeant and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington D.C. His name appears on The Vietnam Memorial Wall on line 47 panel 54 west wall, along with the 15 comrades that were lost on that August morning 1968.

On the Sunday night that I finished writing the draft of this article my phone rang with a South Carolina number that I didn’t recognize. It was 76-year-old Ray Steele a comrade of Gil’s that served with him at the 77-day siege of Kha Sanh and was his barrack mate at Marble Mountain. He explained much of the logistics of the camp and cleared up a few points of confusion about that day. What I appreciated most were his memories of the personal encounters with Secor, who he thought was a good guy, he said Gil was friendly and was easy to talk to. Steele said that he too requested multiple tours in Vietnam. When I asked about his motivation, he referred to the movie Band of Brothers. He said being with his brothers was where he needed to be. Out there they had a job to do and they did it. They were given a different kind of freedom that wasn’t available at traditional Army bases. He said he loved being there.

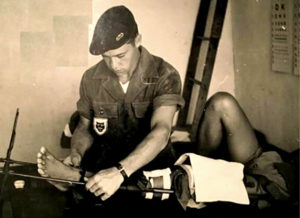

A young medic Gilbert Secor sets a broken leg of a ranger in Vietnam

Gilbert Secor grew up in Hillside and Jersey City, graduating high school from Jersey City. He was among the first Special Force candidates, joining in Germany in 1952 the inaugural year of the legendary commando warriors. He served there for many years with the 10th Special Forces, then 3 years in Okinawa, with the 1st Special Forces before arriving in Vietnam. Both actions in Germany and Japan were in peacekeeping roles, it was in Vietnam that our Hometown Hero seemed to find his passion. Being placed as a charter member with The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG), a highly classified, multi service special operations unit that conducted covert unconventional warfare operations prior to and during the Vietnam war. The innocuous name of his unit was part of its top-secret nature. Secor was part of Operation White Star in Laos, a clandestine CIA mission, as well as covert actions in Cambodia, where military actions were forbidden by congress. While serving outside sanctioned perimeters SOG commandos wore generic uniforms with no markings or dog tags and carried Russian AK-47s or other enemy weapons. All to allow deniability by American military commands. They had orders while in these areas to not be captured alive. Many SOG units suffered 100% casualties and reported the highest percentage of loss of any American battle units in Vietnam.

Eighteen year old Private Gilbert Secor

Secor was decorated with a Silver Star for his actions at Long Vei, a Bronze Star with the V distinction for valor we believe awarded posthumously for his heroics on August 23, 1968, a Bronze Star for merit, The Combat Infantryman’s Badge, The National Defense Service Ribbon with oak leaf clusters and The Senior Parachute Badge, for being wounded twice in battle he received 2 Purple hearts. He was also an advanced scuba diver. In his 36 years Master Sergeant Gilbert Secor spent more than half his life as a professional soldier of the highest degree. We are happy to have shared the life of just one of these very special men that dedicated their life taking orders that put their life in jeopardy at every step. Secor was a member of Cranford’s VFW Post 335 as well as The First Presbyterian Church.

Everyone enjoying freedom today owes a debt to these secret warriors. Master Sergeant Gilbert Arthur Secor was a true patriot and one of our Cranford 86.

Want more? Go to Cranford86.org for additional pictures and YouTube links of several videos and websites that will be of interest for history lovers. Including a harrowing re-enactment of Lang Vei performed by professional actors and an aerial view of the camp at Marble Mountain.

To comment or questions on this article or to ask about opportunities to support The Cranford 86 Project email info@cranford86.org or contact Don Sweeney at (908) 447-6511.

You Tube links: The reenactment of the rescue at Lang Vei.

The multi media presentation from the memorial breakfast for the 50th anniversary of the attack on FOB-4

Secor was an advanced scuba diver, here he is adjusting his buoyancy compensation vest

FOB-4 Special Forces Camp at Danang, S Vietnam

The sixteen Green Beret Special Forces commandos lost on 23 August 1968.

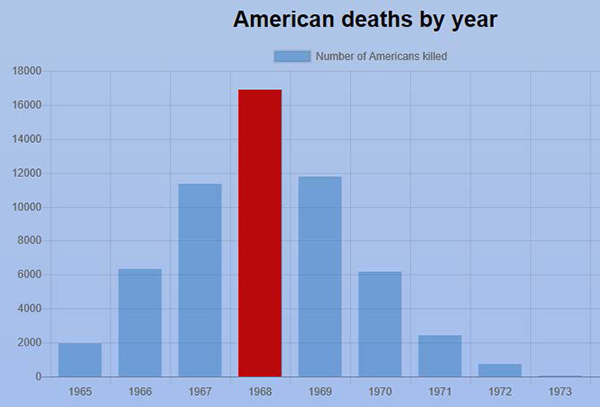

A bar graph that represents the level of intensity that the Vietnam War was experiencing in 1968.

An artistic rendering of the siege at Ple Mei. For Gilbert Secor’s actions that day he received the Bronze Star.

Video From the 50th Anniversary Memorial Breakfast