Private William E. Hinkle .

Meet Private William E. Hinkle, infantryman, One of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney with research by Stu Rosenthal and military proofreading by Vic Bary.

(above) Billy Hinkle with his older Brother Sergeant Lee Hinkle pose with little Thomas Hinkle. Lee’s son.

Thomas went on to serve as a platoon sergeant in Vietnam.

The Cranford 86 project features a hero from our Memorial Park’s monuments each month. Our selection process is different each month. Sometimes we leaf through the many files of accumulated research pages in search for a story that thrills us; other times we are directed by a sponsorship from a family member or organization. Sometimes, as we start a story from a sponsorship, we feel at first there is not much of a story here. Then we go into a research rabbit hole and find we are again amidst yet another incredible, previously unknown memoir, of a Cranford hero. This month an active member of our host organization The Cranford V.F.W. Post #335, Vietnam veteran Bill Hinkle, asked us to research and feature his uncle and namesake William E. Hinkle, his father’s younger brother.

An online search told us that he was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania on December 12, 1919 the youngest of five children, and was baptized William Eugene Hinkle on January 11th, 1920. Moving to Somerville, NJ sometime in the 20s, he attended an eight-week Y.M.C.A. camp in Bushkill, PA and learned to swim there. The obituary given to us by the Hinkle family gave us some more personal information. Billy Hinkle, as his family called him, graduated from Somerville High School in the class of 1938. In 1939 he worked full time as a clerk in a fish market earning $1000.00 for a year for 50 hours a week. His family soon moved to 334 North Avenue West in Cranford. He volunteered for service overseas with the US Army at the age of 20 and was placed in The Signal Corps in Puerto Rico in May of 1940. The United States was not at war then, although World War II was raging in Europe and U-boats in the Atlantic were threatening trade and supply routes. The Signal Corps were working with radio, radar and sonar, technologies that were rapidly developing at the time.

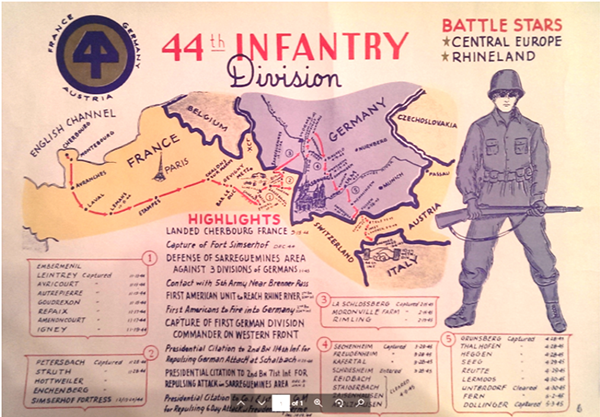

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 plunged the U.S. into war, but Private Hinkle continued his tour in what could be considered an ideal deployment, on a beautiful Caribbean island, safe from any battle action. His three-year service there continued until May of 1944 when he was one of a number of men ordered to report to Camp Crowder in Missouri, before shipping out to Camp Philips in Kansas. There they met up with the troops of the 114th regiment, 44th Infantry Division, 7th Army and trained heavily for nearly four months. Ironically, the 114th was a federalized New Jersey-based National Guard Unit. Although well trained, they had never seen combat and their ages were much older than the average man heading into battle. Bolstering the numbers of a regular army unit with a National Guard regiment was commonplace at this time in the war, an innovative tactic to create the massive quantity of soldiers which would be needed in the battle theater in a few months.

(above) Soldiers from the 44th infantry make the best of the torrential rains that plagued their battle efforts. The fox holes that fighting men used for shelter were for the most part unusable.

Stu Rosenthal, our chief researcher, uncovered a 25-page detailed account by a member of the 114th Infantry regiment. David K. Weiner. In comparing the towns and cities that were in common with those listed in William’s obituary, we felt that they were infantry comrades, traveling the same paths from August to December 1944. Stu also found a book in the Newark Public Library, titled “With the 114th in the E.T.O.” a chronicle of the daily treks of the unit that Private Hinkle was part of. They were amazing finds and would be our guide through the last five months of our Hometown Hero’s life. We were about to enter one of those rabbit holes.

David Weiner met up with Hinkle’s unit in Kansas where he explained that they got their first clue of what continent they would be heading to, now that they had completed their training. When they were issued wool uniforms, they knew that the South Pacific was too hot for wool clothing, so they must be heading to Europe. Up to that point, no one had given them any idea of what their future had to offer. Infantrymen were given information on a need to know basis.

From Kansas, the 114th was moved to Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts in late August 1944, departing from Boston Port on September 5th. The Weiner memoirs told of a crowded ocean craft, the General J.R. Brookes, that the soldiers had surmised was a shuttle to bring them to the large luxury ocean liner that would transport them to Europe. To their disappointment, this was their vessel for the entire trip. A loudspeaker announcement as the ship was about to depart blared, “We’re going to France.” It was the only tip they received of their destination. It was an 11-day trip on smooth seas surrounded by a mighty convoy of battleships and armored support vessels. They arrived in Cherbourg, France, just minutes from Normandy. This was the first time US troops were brought directly to France. Before, all GIs were sent to England and then to their European destination. Acquiring the deep port of Cherbourg was part of the grand plan of the Normandy invasion. A commercial seaport would be a crucial element of the supply chain, needed to fuel a demanding army.

With the successful landing three months earlier of over 150,000 troops onto the beaches at Normandy, the Allied forces were now under the supreme command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. His plans were to create a wide, nearly 300-mile front that would liberate French towns and villages as the united Allied forces swept through France on their way to Berlin. The British commander, General Montgomery, fiercely objected, proposing a narrow intense passage through the French countryside to directly take Berlin in a mass concentration of power. The decision was made to follow Eisenhower’s broad front plan. The forces to take on such a task would require close to 40 divisions, nearly one million soldiers.

The 44th infantry arm patch that would have been worn by Private William Hinkle.

The inexperienced but well trained 114th Infantry regiment spent another month in Cherbourg working on language and culture, preparing for their insertion into the French population. They travelled by train below Paris for four days to the town of Chanteheux, where they were welcomed by the townspeople and stayed the night in a schoolhouse. The next morning, October 18, Hinkle’s regiment headed out, encountering their first combat action.

The German Army at this point in the war was in retreat, continuing a repeated strategy of pulling back and then regrouping. Paris had just been liberated and Italy had surrendered. The 114th did meet violent resistance in some towns and villages along their path, taking many casualties. However, in many encounters they were met by tired German troops who had had enough of war and were waving any white flag they could find. Managing the many surrendering German POWs became a growing task. Rumors that the war would be over by Christmas were also passing through the troops. The reality was not so simple; many hard-fought battles still lay ahead.

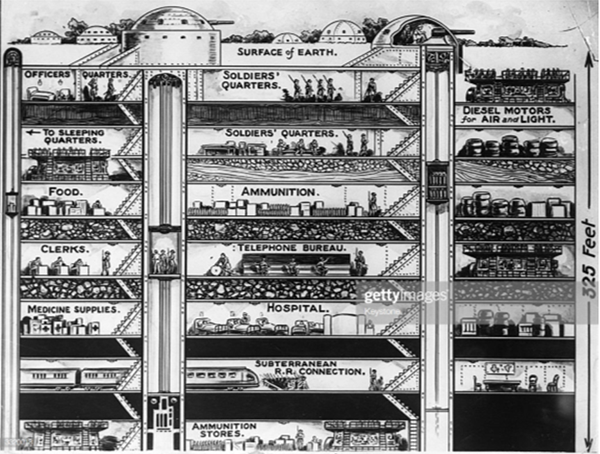

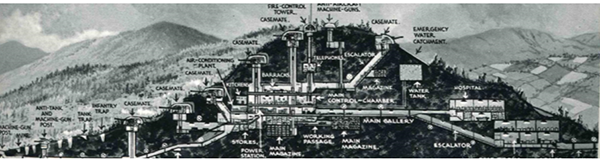

The mission of the 7th Army was to secure several paths through the heavily fortified Vosges Mountains, across the famous Maginot line. It had been built by the French themselves to protect their eastern border from the many attacks from Germany and Italy throughout history. No defender held up in the many fortresses and steel gun turrets had ever been defeated. The steel was up to twelve-foot-thick and some of the bunkers were eight stories deep. There was an underground railway to transport soldiers and deliver munitions to the big guns. The Maginot line had been in the hands of the German’s since the surrender of the French Army in 1940. The one fact that encouraged the Allies as they approached the intimidating 450-mile series of fortresses was that all the big guns faced Germany, not France.

On October 25th, Hinkle’s unit saw its first violent encounters with German forces; they fared well taking some casualties. On November 13th they successfully liberated their first two towns – Dossenheim and Avicourt. The townspeople had been under Nazi rule for over four years. The resultant celebrating by the liberated French people was something the men of the 114th would see frequently in the days ahead.

At this point, the 7th Army joined and supported the 2nd Armored Division of The Free French Army as they attempted to liberate Strasbourg, the capital of the Alsace region. General Charles De Gaulle, commander of the re-formed French Army, requested that the French Army retake the historic city. Because of the collapse of French forces and their surrender to the Germans on June 22nd, 1940 it was felt that the uplifting of the beleaguered French population was important. There was a large Nazi presence and regional headquarters at Strasbourg. Adolf Hitler had issued new orders to all German units. Retreat would no longer be an option. German forces were to stand their ground and “fight to the last round.” In a violent one-day battle on November 23rd, the combined French and American forces defeated the Germans and liberated Strasbourg. 1,200 Germans were killed, and 12,000 prisoners were taken, including 4 generals. The victorious Allied troops took full advantage of the urban shelter and the seemingly unlimited supply of French women and spirits.

The celebration didn’t last long; the following day orders were given for the units of the 114th to confront a tank corps of 22 Panzer Mark V tanks, Germany’s best armored ground weapon, with its fierce 88mm gun. If not for their actions in a David and Goliath battle, it was thought that their mission would have been thwarted. For the unit’s valiant actions on November 24th they were awarded a Presidential unit citation.

The units of the 114th were embarking on separate paths as they continued through the Vosges Mountains. The memoirs of our two members of Hinkle’s unit tell of continued acts of bravery and of many more liberations of towns and villages as they continued their journey to the Rhine River. The names of the passing towns and villages now were different from each memoir. It is impossible for us to be certain whether the battles that we have details of were experienced by our Cranford Hero. The enormity of his unit, 15,000 men, allowed them to have many encounters that happened concurrently. Although we know he was in Company A, the nature of the battles they many times engaged in involved a mixture of various companies. Some accounts were reported without any mention of what battalions or companies were involved.

The weather was particularly bad that winter with constant snow and torrential rain; it made for hellish conditions. The ability to take shelter in fox holes was for the most part eliminated as a defense or for sleeping, as the ground was so flooded that a fox hole would fill with water as soon as it was dug. Trench foot was rampant.

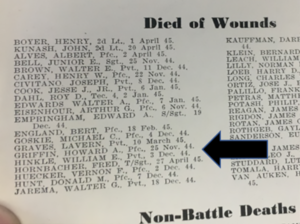

(above) A listing of war dead from “With the 114th in the E.T.O.”

Our records tell us that Private William E. Hinkle died on December 3rd, 1944 from his wounds received possibly, prior to that day, nine days before his 25th birthday. We know that after the Panzer tank encounter on November 24th, the 114th had battles in several small towns – Petersbach, Struth, Hinsburg, Fromuhi, Tiefenbach, Weisslingen, Volksburg and Montbronn. Most of these towns were protected by German infantry and artillery. The fighting during this 9-day period, although sporadic, created many casualties on both sides. David Weiner says that these battles stand out in his mind as some of the most violent days of their mission. While we have confirmed that Volksburg was the 114th regiment’s battle on December 3rd, 1944, we cannot be certain that Hinkle died from injuries received there. In the book “With the 114th in the E.T.O.” Hinkle is listed as “died of wounds on December 3rd”, not “killed in action December 3rd”.

The 114th Infantry regiment, 44th Infantry Division, would continue in its trek across the Vosges mountains and would be the first attacking army to defeat a defending force in control of The Maginot Line and would accomplish their goal of reaching the Rhine River. Their 190 days in battle would end on March 15th, 1945. Of the approximately 15,000 men that started in Chesbrough on September 15th, 1,008 were killed in action, 4,650 were wounded, 434 were listed as missing and 19 captured. There were many medals awarded for bravery, including: 15 Distinguished Service Crosses, 2 Legions of Merit, 260 Silver Stars, 4 Soldiers Medals, 1,515 Bronze Stars and 98 Air Medals. In total, an amazing 41,474 German soldiers were taken prisoner, many of them women.

Publicity about the 114th’s intense fighting and heroic performances was very light at the time, due to the many other battles being fought at the same time. General Patton and the 3rd Army, and General Bradley and the 1st Army, were involved in the bloodiest encounters of the war at The Hürtgen Forest, The Battle at Metz and The Battle of the Bulge. Several other Armies were also pressing across France at the same time. Sadly, history books today often overlook the successes of the 7th Army and the 44th Infantry Division in the Vosges Mountains with their relatively unknown general, Robert L. Spragins. What they accomplished there was historic. They generally completed these feats without mechanical means of transportation or air support due to the needs of other armies. Gasoline was very scarce since all supplies were traveling by truck from Normandy, hundreds of miles away. These older than most, inexperienced New Jersey National Guardsmen, performed valiantly without much outside support. General Eisenhower’s idea and execution of the broad front attack through France and the million men and woman who carried it out may have saved the world from fascism.

William E. Hinkle’s Grave marker at Graceland Cemetery in Kenilworth

William E. Hinkle, one of those men, was buried for a short time in France and was returned to Cranford on April 21st, 1949. He was buried with full military honors at Graceland Cemetery in Kenilworth. He was a brave patriot and one of our Cranford 86.

A YouTube search for the 114th Infantry regiment turned up an amateur video interview with an old soldier telling his eyewitness accounts of his time with Hinkle’s unit. It reflected the emotional attachment that a soldier had to his brothers in arms as well as the compassionate feelings the American soldiers had for the captured German POWs. See this video as well as other links to the many sources we used to create this tribute on Cranford86.org.

A diagram of the underside of a typical fortress that supported the big gun turrets of the Maginot Line. Underground railroads transported troops and ammunition throughout the 450-mile string of defensive structures built by the French to protect their northern border from Germany and Italy.

(above) A simple map of the mission that the 114th regiment, 44th infantry was to carry out.

Note the cathedral at Strasbourg.

(above) The General J.R. Brooks, the transport ship that carried the 114th regiment of the 44th Infantry Division to Cherbourgh France from Boston Port on September 5th, 1944.

The 114th infantry regiment armpatch.