Meet Ensign Howard Goodman, engineering officer, One of Cranford’s 86 Hometown Heroes.

By Don Sweeney with Lt. Col. Steven Glazer (Ret.), Cranford Historical Society

Stevens Graduation Portrait.

On Memorial Day 2016 the idea of telling the stories and introducing the faces of our Cranford Hometown Heroes came to me. One of the first stories was told to me by my neighbor Mary Roberts and her family. Mary’s uncle, James “Jimmy” Roberts, was a casualty of World War II while serving on the heavy cruiser USS Canberra (CA-70) in the waters off Formosa, now known as Taiwan. The story we previously shared here told of a brotherhood of three Cranford High School graduates, Jimmy, Joe Griffin and Bob Greco, who left for war before their formal graduation ceremony, later serving together at sea. What I didn’t know until later was that Jimmy Roberts wasn’t the only Cranford Hometown Hero killed on that Friday the 13th in October 1944. While working on story number five, about William Asa Hale, a graduate of Stevens Institute of Technology, we stumbled upon a full list of Stevens students who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country. On that list was Ensign Howard Evans Goodman of Cranford, along with the date October 13, 1944. The “coincidence” caught our attention. Upon further research we found he too was on the Canberra. I immediately called Mary Roberts and asked if she had heard anything about another Cranford sailor on the ship with her uncle, who perished on that same day. She said she hadn’t, but would ask her family. It seems that they did indeed know about Ensign Goodman, but it wasn’t until well after the memorial services for their loved one that they read Goodman’s story in the Cranford Chronicle. She simply said that they heard Goodman wasn’t on the ship long and her Uncle Jimmy didn’t really know him. The article from the Cranford Chronicle was mentioned in a book by prominent Cranford historian Bob Fridlington and uncovered by Steve Glazer. The book and the article confirmed the fateful circumstances. Fridlington’s book had a vintage photograph of Fireman 1st Class Bob Greco and a brief retelling of the story of the four young Cranford men and their time together on the Canberra. Greco and Griffin had been amazed to learn from their hometown newspaper that another local man, Ensign Howard Goodman, was a shipmate who also died in the attack. According to the article, Goodman had only been on the Canberra for several weeks before giving his life for his ship and her crew. Maybe it is just as well that we can now tell his story and introduce his face. Howard Goodman, like many Cranford residents, was born in Bayonne. He moved to Cranford in 1922 at the age of 4. He and his family were members of Trinity Episcopal Church. While in Cranford High, he held a student government office each year and was elected president of his senior class. He was a member of the National Honor Society, Mathematics Club, Latin Club, Foreign Affairs Club and served as Art Editor of the Golden C. His classmates voted him “the boy who had done the most for his class” and “the most industrious student.” He graduated with the class of 1935 and then attended Colby College in Maine for one year before transferring to Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken. After graduating with honors from Stevens in 1940, he was employed by General Electric Co. as a turbine engineer in Lynn, Mass., a premium job placement for a graduating senior. In April 1944, after four years with General Electric, Howard volunteered for service with the U.S. Navy, receiving his eight-week indoctrination course at Princeton University, where he was commissioned an ensign.

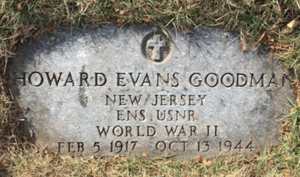

Ensign Howard Evans Goodman’s footstone at Fairview Cemetery in Westfield.

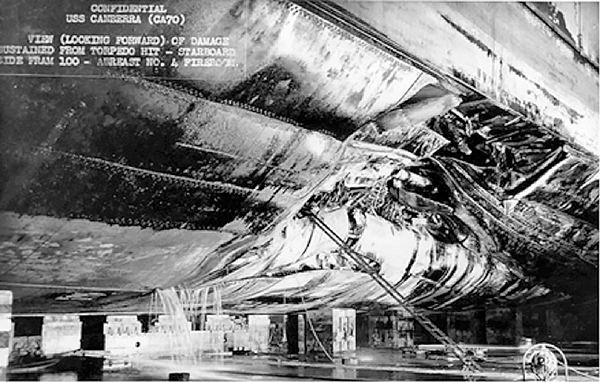

He left for San Francisco on August 2, 1944, for a “special mission” in the Pacific Theater. In early October 1944 he was placed on the Canberra off the coast of China. It would seem the special mission the newly minted ensign was being trained for was the attack on Formosa. The island’s airfields were the source of continuous sorties on the Allied positions on land and sea. Elimination of the source could change the outcome of the war in the South Pacific. It was from Formosa that the first kamikaze attacks originated. And it was the location of the largest concentration of Japanese aircraft in the region. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the U.S. Navy’s 3rd Fleet, had moved his Task Force 38, the largest collection of naval battle hardware in the Pacific, to the waters off the coast of Formosa. Halsey — a native of Elizabeth, NJ — planned to destroy these airfields and the hundreds of attack aircraft based there. The enormity of the American naval might collected there was reported to be 17 aircraft carriers (nicknamed “Murderers’ Row”), 4 heavy cruisers and 11 light cruisers as anti-aircraft support vessels, 57 destroyers and 1,425 bomber/fighters. It was clear the Navy was serious about this special mission. The attacks on Formosa commenced on October 10 and continued through the 20th. On the evening of Friday the thirteenth — after 3 days of bombardment by the big guns of American destroyers and repeated air strikes — a Japanese attack squadron of 30 planes flew below radar coverage setting out to defend their island. These bombers were Mitsubishi G4m and Yokosuka P1Y Frances, T-Buntai’ torpedo bombers. More than 20 were downed by naval anti-aircraft fire. 10 bombers got past most of the perimeter defenses and were able to attack the aircraft carriers directly. These dual engine T-Buntai’ planes were a secret weapon being held back by the Japanese to surprise the American Task Group at a strategic moment in the war. The torpedoes were controlled by a radio wave too low to be detected by the allied forces. 6 remote controlled torpedoes were launched and aimed at the carriers. Luckily the violent seas caused 5 torpedoes to miss their marks, either going off course or going too deep underneath the carriers. One however missed the aircraft carrier Franklin and struck the Canberra just below the water line and its armor belt. A jagged hole 55’ X 140’ was blown into the engine room, killing 23 of the nearly 1750 men on board. Of those killed in action that day, Ensign Goodman was the only officer. Within one week General Electric engineers developed a blocking device which rendered future use of the T-Buntai ineffective. Nevertheless, the battle was one-sided, as the Americans had air superiority due to better equipment and training. With the Japanese air corps devastated, their ability to defend the Okinawa Islands in the upcoming campaign was compromised. Over ten days of sustained warfare, the Japanese lost numerous ships and approximately 500 aircraft, almost their entire air strength in the area (with American losses amounting to 89 aircraft and two heavy cruisers). The Canberra and the USS Houston were damaged but not sunk. The battle of Formosa was a great victory at sea and instrumental in our strategic success at the later battle of Leyte Gulf off the Philippine Islands on October 23-26, 1944. It was said by many to be the largest and most fierce naval battle of WW2, some said of all time. Steve Glazer remarkably was able to locate a surviving crew member of the Canberra crew and interview him on the phone.

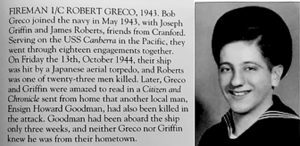

(above) Bob Greco was the veteran that read the names of the WW2 honor roll for years on Memorial Day. He said as he read the names he saw the faces. It was that thought that has inspired the Cranford 86 Hometown hero project. He was aboard the USS Canberra with Ens. Howard Goodman and James Roberts.

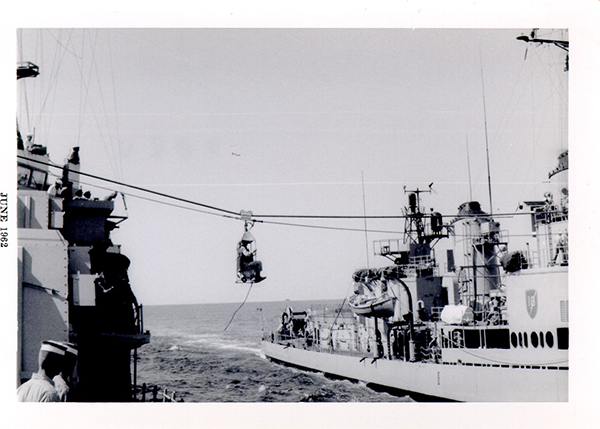

John Chenoweth, 93 years old, gave us a first-hand report about the battle and Ensign Goodman, who he remembered vividly. He described Goodman’s grand entrance onto the Canberra just 10 days before the battle that took his life. He was brought on board from the USS Santa Fe in an open sea procedure called “highlining.” While the two ships were moving in open seas, a cable car of sorts was created and Ensign Goodman was transported from one ship to another. It must have been something to see. Mr. Chenoweth told us that Ensign Goodman was an engineering officer working in the engine room that night. That is consistent with the story of James Roberts. Howard Goodman was originally interred on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, where the Canberra put in for repairs. However, like so many others lost in battle on distant seas and hostile shores during the war, the young man’s remains were not returned home until years later. In 1948, he was buried in Fairview Cemetery, only a short walk from 39 Spruce Street, where he grew up in town. The Hometown Hero was awarded the Purple Heart and Asiatic medals for making the supreme sacrifice at age 27. Every month as we collect the details to create a new Hometown Hero story, I find myself getting emotionally attached to the life of each of these young men. This month is no different. Reading the 1987 obituary of Goodman’s 95-year-old mom, and the loving attachment mentioned there that was broken by the untimely death of her first-born child almost a half century earlier, had me thinking about how my wife and I might have been affected under similar circumstances. Our son, as was Howard Goodman, is an engineering student at Stevens Institute of Technology and will hopefully soon land that prestigious dream job and start a life and family of his own. If times were to change and war was again calling young men to service, we could be a family just like the Goodmans. It’s feelings such as these that drive me to complete as many stories of the Cranford 86 as we can. Watch each month on our Facebook page at cranford86, or on rennamedia.com in the Cranford86 file. Ensign Howard E. Goodman was a great American and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes.

YouTube clips. Highlining a high Sea transfer of sailors from ship to ship,

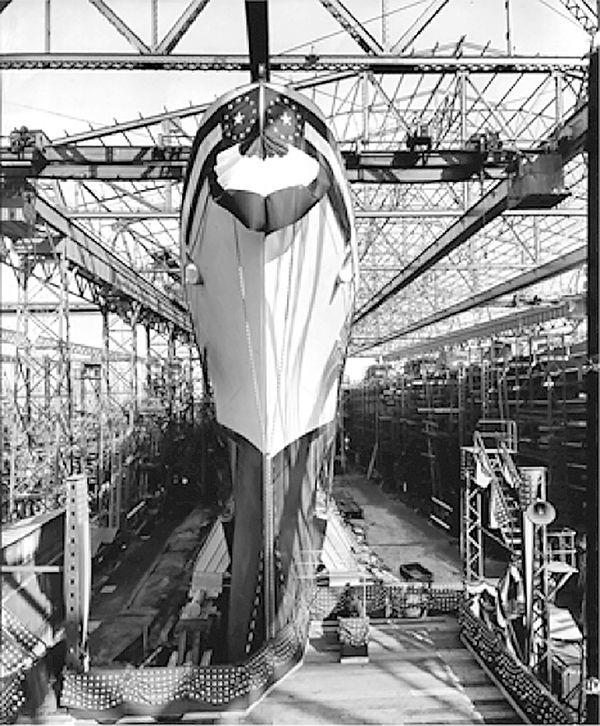

USS Canberra on christening and launching day April 19, 1943.

Aerial T-Buntai’ torpedoes that were dropped from aircraft during the battle of Formosa.

The 3rd Fleet’s Task 38 nicknamed ‘Murderers Row”

The USS Canberra as it looked on Friday the 13th, 1944.

A formerly classified photo of the damage caused by the torpedo attack on The USS Canberra.

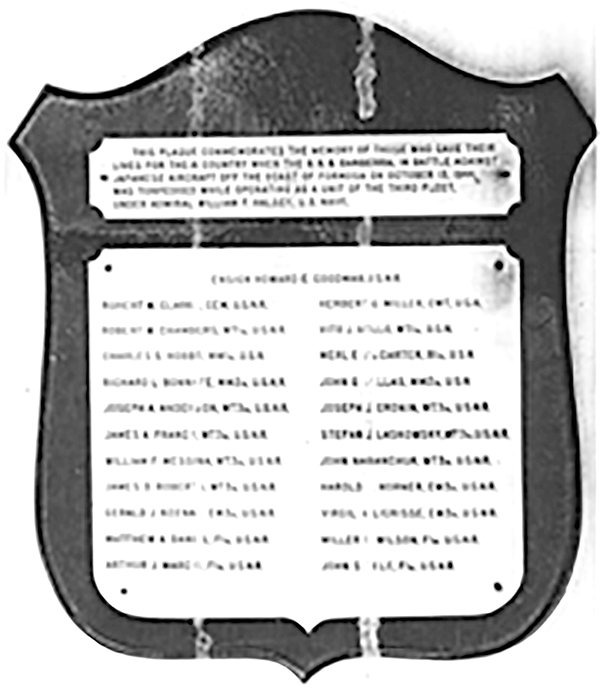

A plaque that hung on the wall of the USS Canberra until its decommission in 1970.

Naval Highlining transfers a seaman while at sea.