Arthur J. Galvin, One of Cranford’s 86

Going into our fourth year, the Cranford 86 team continues its mission, to reintroduce each of the men listed on our township’s honor roll. We share with our readers, the details of what each of these servicemen has encountered while defending our freedom and preserving our American way of life. Although most of us have some knowledge of D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, Okinawa, Iwo Jima and other famous battles, it is not until one dives deeply into history, that we can really start to understand what tribulations that members of our American military have experienced. The simple words, “Thank you for your service” are usually delivered with heartfelt sincerity. But many times, they may be said without the actual realization of what hardships may have confronted that veteran who stands before us. For each hero profile that Cranford 86 has delivered so far, we have provided the historical information that describes how one of Cranford’s own was taken from us. We hope that our work also provides awareness as to the types of events that the veterans who have come home to us may also have experienced. Our team of four volunteers has vowed to continue working towards the 86th story. With the knowledge that we provide it can be realized by all, the level of respect and gratitude that is due to all of our honored military.

In our latest story, we will follow a Cranford hero, as he first becomes highly trained in state-of-the-art weaponry and then goes on to serve under a great, yet controversial general in a grueling, pivotal operation in Europe. Referring back to the Juan Bargos story, from WWI, we learned about the beginnings of the primitive two-man tank, something in which young army officers Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton were involved in, early in their military careers. In the years that passed between the two World Wars, there was little innovation in American military aircraft or mobile armaments, as our country’s eye mistakenly had been taken away from the need for war tools. As the 1930’s ended, the production of military equipment in Germany and Japan escalated. This became the trigger that launched America into artillery-based development, manufactured by American industrial titans. Our ground forces, which had still been using the horse as a method of mobilized attack, were about to take a giant step forward in the form of new, mechanized mobile army units. On April 15th, 1941, the creation of the 4th Armored Division placed 14 subunits into service. A 54-year-old LT General George Patton was appointed to command its development. In Pine Camp, which is present day Fort Drum, in upstate New York and Fort Knox in Kentucky, mobile armored training facilities were created. Soon 3,200 enlisted men and 600 officers began training on newly created high-tech war machines and those numbers would grow quickly to total 10,000. The attack on Pearl Harbor December 7th, 1941, would further ignite the development across the board in American armament. An acceleration of manufacturing and training would now reach a fevered pitch as America and its allies would eventually amaze the world. A sleeping giant had been awakened.

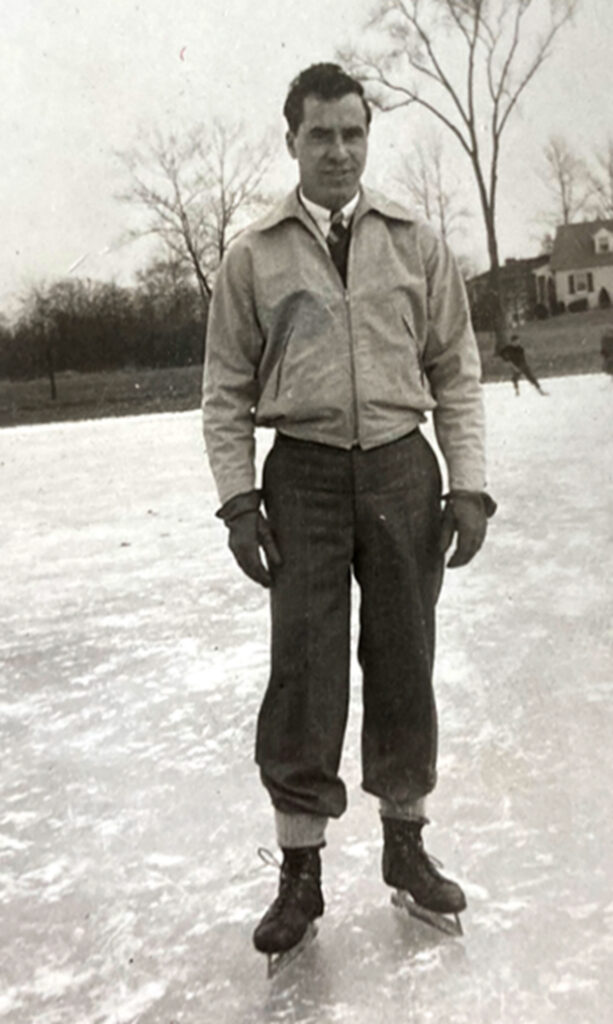

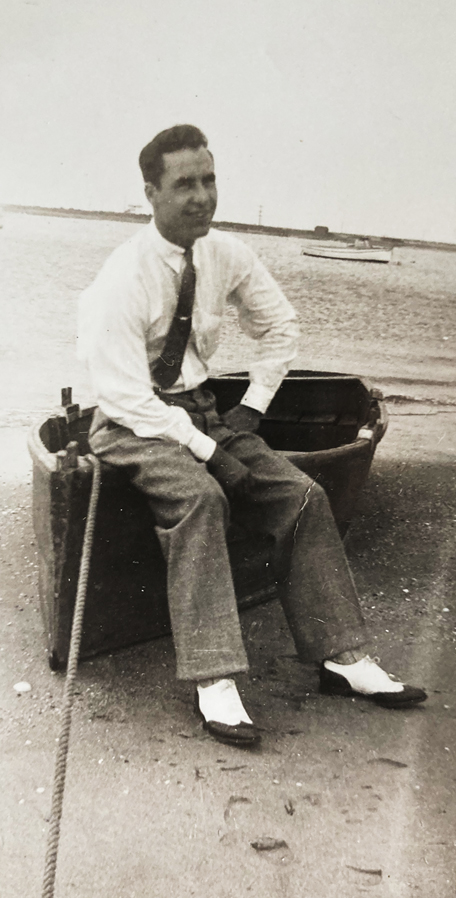

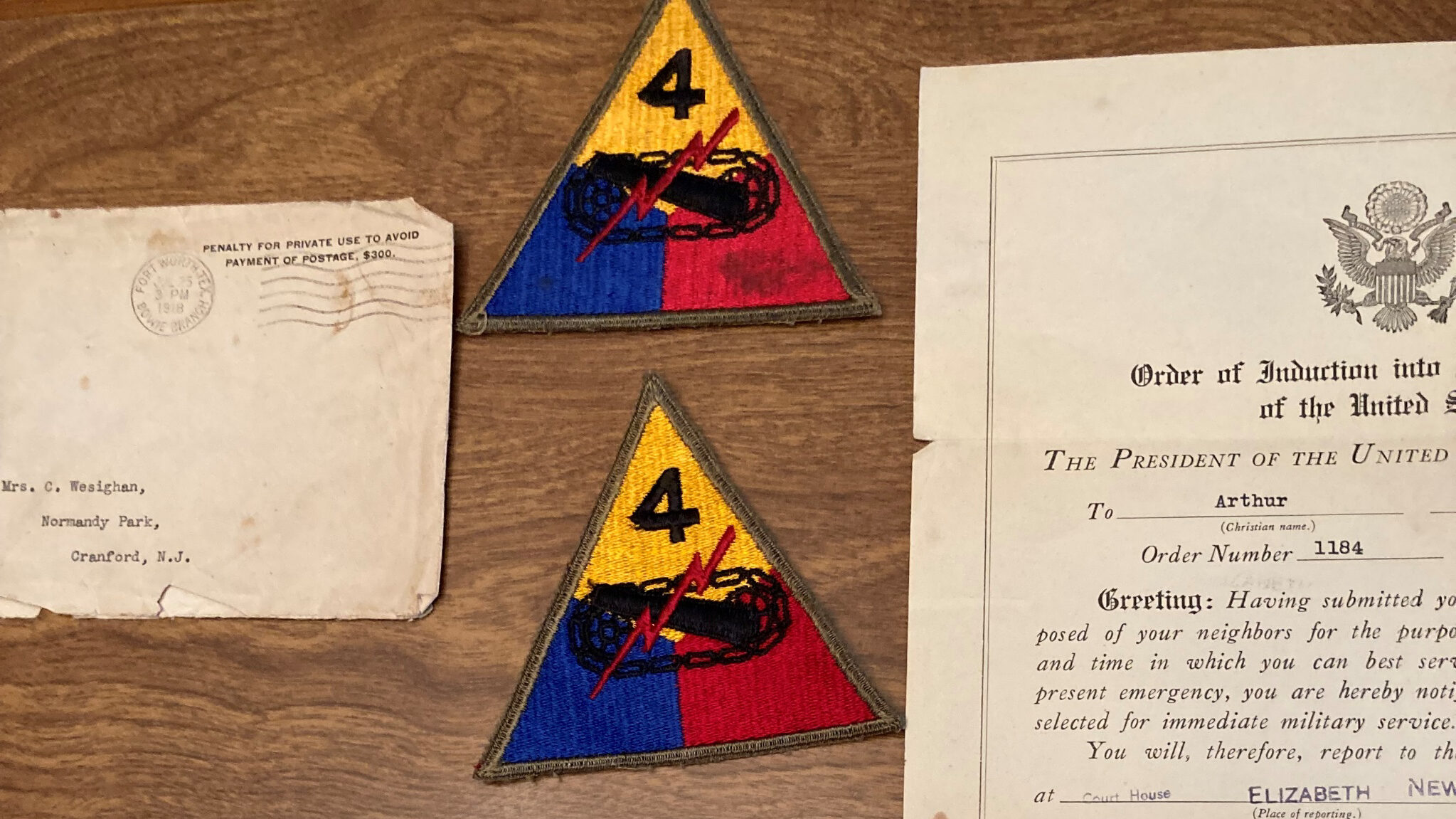

Arthur James Galvin was born on November 26th, 1914, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He was named after his uncle, Arthur Wesighan, another Cranford serviceman who lost his life while in the service of our country. Arthur Wesighan died during WWI, on July 21st, 1918, from injuries incurred in a motorcycle accident. Ironically, the accident occurred at Camp Bowie in Fort Worth, Texas, one of the facilities at which his nephew Arthur Galvin was trained. The Galvins moved to Cranford, to 830 Springfield Avenue, when Arthur was five years old. Arthur’s dad, Edward, was a Cranford police officer for over 21 years. Arthur attended Grant and Roosevelt elementary schools as well as Cranford High School. The family belonged to the First Presbyterian Church in Cranford. Young Arthur seemed to enjoy life, he loved outdoor sports, especially ice skating, at which he excelled. He was an avid hunter, fisherman and trapper. While indoors, he loved to read about and sketch wildlife. Arthur was a talented artist who also loved drawing airplanes. He spent a lot of time at local airports and eventually enrolled in flying school. After high school, Arthur began working at Western Electric in Kearny. Then, as others before him had done, Arthur left his family, his gainful employment and we believe, a steady girlfriend from Cranford, to join our country in fighting a World War.

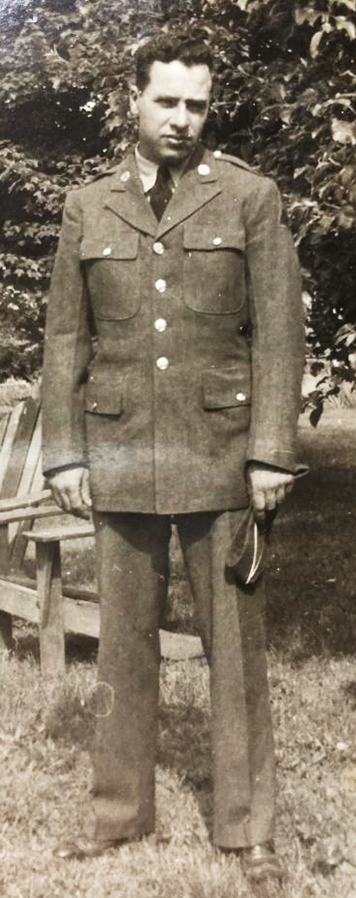

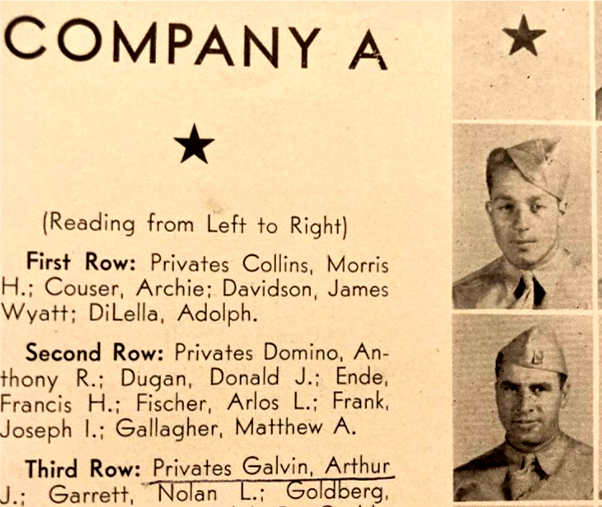

On February 20, 1942, Arthur Galvin, a 27-year-old, 134-pound, five-foot seven-inch Cranford man enlisted for duty in the US Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, for basic training. He was relocated to Fort Knox in Kentucky on May 20th, 1942, where he was enrolled into the Armored Force Replacement Training Center in Company A, 1st BN, 2nd Platoon, on track to become a specialized soldier of the highest level. Fort Knox was headquarters of the National Tank Training Program (See the graduating class photos at Cranford86.org). From there Arthur was moved to Pine Camp in upstate New York where Patton’s newly formed 4th Armored Division had begun its training. It is here that he was trained in severe weather tactics into the winter of 1942. The yearbook of the 1942 Pine Camp graduating class was provided to us by the Galvin-Parsell family. It revealed the level of advanced training received by our hero from a country preparing a force for the new world of high-tech war tactics. From Pine Camp, the 51st Battalion of the 4th Armored Division, to which Galvin was assigned, would relocate to Camp Forrest in the Tennessee countryside near Nashville. Arthur was stationed there from September to October, 1942 in an area selected by LT General George Patton for infantry training because its hills closely resembled the terrain of France, Belgium, and Germany. From there the 51st would travel cross country by train to Camp Ibis near Needles, California in the Mojave Desert, outside of Los Angeles. The barren land there would allow for wide open artillery training without the fear of civilian danger. The Colorado River there was used for aquatic exercises. General Patton, a California native, had started using the desert for training earlier in the war to simulate the environment of the deserts in Northern Africa. In the eyes of many observers, Patton’s accomplishments and victories in 1943 in Africa made him the most successful active commander in the US Army. After several weeks in California, the 51st Armored Battalion arrived at Camp Bowie in Texas on June 3rd, 1943, it was here that many 51st members would be shifted to the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion. Without any official source regarding the redesignation of the 51st to the 53rd, we asked Arthur’s family. Rose Parsell reported that the battalion’s name within the return address, on the steady stream of Arthur’s letters home, at this point had changed. They would train there in advanced maneuvers until December when they departed for Camp Miles Standish in Massachusetts for more winter training. Cranford 86 researcher Stu Rosenthal discovered a marriage certificate that shows Arthur Galvin marrying Ruth Brandenberg of 24 Bloomingdale Avenue, Cranford in 1943. Since Arthur was in California, Tennessee, and Texas through much of that year, we surmise that Arthur and Ruth found the opportunity to be married in New Jersey while Arthur was stationed in Massachusetts, just before he went overseas. On December 29th Arthur and his battalion departed for England where they would stay until eventually making their way to Normandy.

In General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s preparations for the largest amphibious landing attack in world history, it is important to our story to explain the diversional tactics that were put in play. The Germans had been, for some time, expecting an allied assault on the European mainland. The Nazis had created a 1500 mile long wall to protect the Atlantic coast. If they could predict where along the wall that the allies would strike, they could concentrate their armament and troops there and increase their chances for a victory. With Patton’s recent successes in Northern Africa and in Sicily, the Germans felt that Patton and his Third Army would be principal players in the offensive plan. However, it was unknown to the Germans that Patton had been relieved of his command in December, 1943 when the American press learned of him striking two hospitalized soldiers who were being treated for combat fatigue.

Staging Patton in England was part of a ruse to trick the Nazis into thinking that the impending attack was coming from Great Britain to Calais. Located near Paris, almost 150 miles north of Normandy, Calais is situated where the English Channel is at its narrowest. The Germans were led to believe that an army of 12 divisions (a division contains 15,000 troops), with Patton in charge, was situated in England directly across from Calais. But in reality, it was only a “ghost army”. Phony radio transmissions and even fake inflatable tanks and aircraft battalions were created to throw off German intelligence officers who were watching Patton’s every move. A professional actor posing as famed British General Montgomery made several impromptu appearances in England to enhance the deception. Captured German spies were fed lies and released, bringing that erroneous information with them, back to the Nazi headquarters. Intelligence reports showed that the ruse worked. The Nazis staged several tank battalions and a large fighting force at Pas-de-Calais, even after the D-Day attack began.

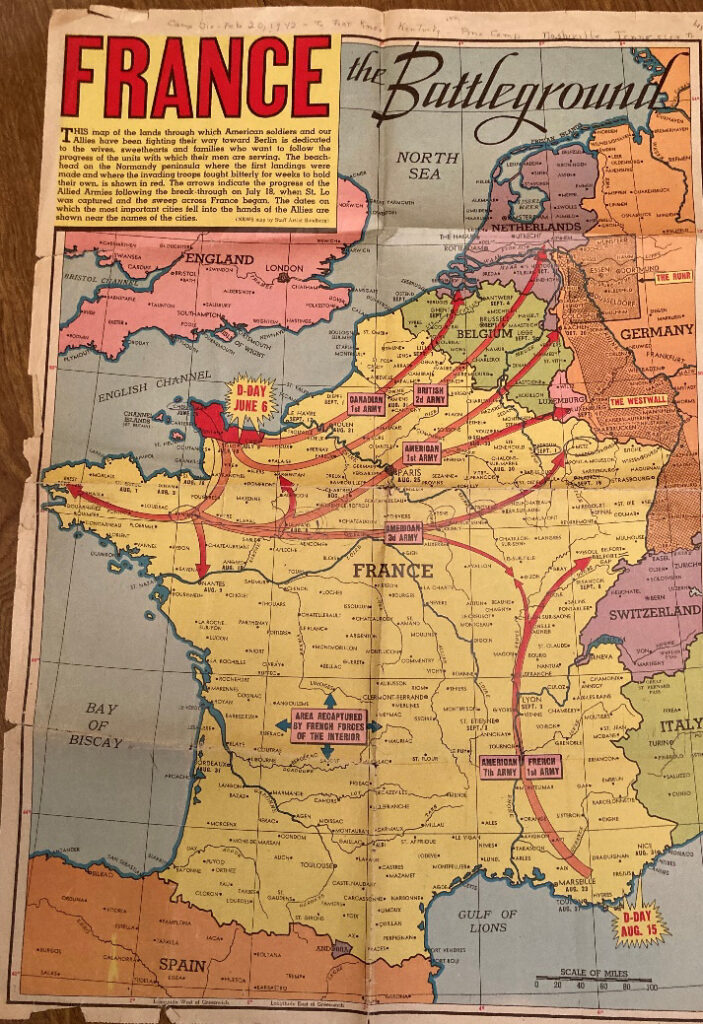

Finally, with over two years of intense training under their belt, the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion with PFC Arthur Galvin, along with the enormous might of Patton’s Third Army, would cross the English Channel and land on Utah beach. To get an idea of the scope of this movement, the Third Army was traveling with 933 tanks, 672 of which were M4 Sherman Medium Tanks and 261 were M5A1 Stuart Light Tanks. The tanks were accompanied by nearly 100,000 men and thousands of other mobile artillery cannons and motor vehicles. Their arrival was five weeks after the initial D-Day landings. The 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, (Arthur Galvin’s unit of 700 men), under General Patton would now see their first combat, supporting General Omar Bradley during Operation Cobra in late July of 1944. Victory here would break the last stand of the German Army in the Normandy region. The addition of some 100,000 rested, well-trained soldiers with over a thousand light and medium weight tanks, self-propelled Howitzer cannons and Hellcat Tank Destroyers were a welcome addition to the operation. When the hard-fought battle ended it left over 100,000 combined dead, but finally ended a stalemate situation in the Normandy region. The Third Army with the 53rd would spend the last part of August supporting the effort to capture the Port of Brittany as it was badly needed by the allies. At that time, all supplies were still coming into the battle theater from the beaches of Normandy via Mulberry harbors. At this point in the war, the Germans had been beaten back by the invading allies and had retreated to set up a western defensive line to repel the advances of the combined allied forces which were now headed for Berlin.

General Patton had not been given the lead role in the D-Day attack, which he thought he deserved and he did not play supporting roles well. In August however, General Eisenhower would order General Patton to head west toward the Rhine River, solely in command of his Third Army. In his famed Patton style, he spearheaded the Third Army, with the 4th Armored Division’s, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion and 13 assorted units across France covering nearly 400 miles in about a week. He used innovated air reconnaissance techniques, even deploying a single engine nonmilitary, personal aircraft, to help to ensure the safety of his men. His highly motivated soldiers moved in a fashion not seen before in American warfare. General Patton was not in favor of foxholes or slit trenches and he was quoted as saying that “an army in a defensive stand was an army awaiting slaughter”. Another quote that he was famous for was “a pint of sweat could save a gallon of blood”, referring to the excessive training that he required his men to complete. The one big problem had by Patton’s Third Army, was that the enormous amount of gasoline that was needed to push a couple thousand armored vehicles across the French countryside, was not available. Each of their 600 36-ton M4 Sherman Tanks, with up to 10-inch-thick armored plates, got approximately one mile per gallon. General supplies were also in need of replenishment. Three hundred miles to the north, British General Montgomery was involved in Operation Market Garden (featured in the movie, A Bridge Too Far) which was in action concurrent to Patton’s attack. General Eisenhower deemed Market Garden as a higher priority. Keep in mind that during this period, 700,000 troops from England, United States, Canada, and France were all moving across the French countryside. Patton’s allotted fuel supply had run out leaving his army waiting near Metz for resupply.

On September 15th, General Eisenhower granted the 53rd enough supplies for Patton to advance across the Moselle River near the town of Nancy, and possibly advance to the Rhine. There the 2ndCalvary was holding off a German Panther Reconnaissance Battalion outside the town of Luneville. The 4th Armored Division came to their assistance, but what they had not realized was that this small reconnaissance battalion was the tip of an iceberg. The Germans were in the beginning of gathering several tank divisions for an upcoming offensive. One German SS brigade was armed with 17 brand new Panzer IV tanks, sporting 75mm high-velocity cannons, which were bigger and stronger than anything in Patton’s mobile arsenal. That brigade had an additional 40 other tanks and armored vehicles. Just miles away and approaching were two similarly armed other brigades and still more were coming. The Third Army consisted of four tank brigades and three armored battalions as well. The Americans, while well equipped, were outnumbered and under armed. But, luckily for the Third Army, the Nazis were thin on well-trained soldiers and operators of their superior fire power. Also, in the Americans favor, was the air support from the XIX Tactical Air Command and its 400 fighters and fighter bombers. The Americans also had outstanding tactical commanders. Led by famed officers from the United States Military Academy at West Point, Major General John Wood of the 53rd Armored Infantry, Colonel Reed of the 2nd Calvary, Major Pitman of the 42nd Squadron and General Patton. The Americans were victorious at Luneville after a fierce four-day fire fight. On the 19th of September the Germans would retreat and move 12 miles north to Arracourt, but this battle was far from over.

The 53rd Battalion’s commander, General Wood along with Patton himself would pursue the fleeing German Panzer Battalions and would engage them at Arracourt. At this point in the story, as I have done many times before, I found myself wondering exactly where was our Cranford hero Arthur Galvin now, as he and his battalion moved further and further into France. There had been numerous attacks and victories being matched with equal counterattacks and recapturing the same objectives repeatedly. The fighting at Arracourt continued until September 29th and in the end was considered a stalemate. The German Panzer forces had been so badly mauled by Patton’s army that they were incapable of any additional offensive action. It was said to be the largest armored contest between the German and Allied forces in the European Theater of Operations to that point in the war, but was dwarfed just 3 months later by the Battle of the Bulge, which General Patton and his Third Army were a large part of as well. The blow-by-blow accounts of this month-long non-stop battle of heavy metal was heart pounding and hard to even fathom. Links to the reports that we were able to find and a YouTube video of the Battle of Arracourt are on the Cranford86.org version of our story. The shortage of fuel again foiled Patton’s plan to move forward in pursuit of the enemy toward the Rhine River. After the battle Patton received orders from General Eisenhower to stay put and go on the defensive, not a position Patton was comfortable with.

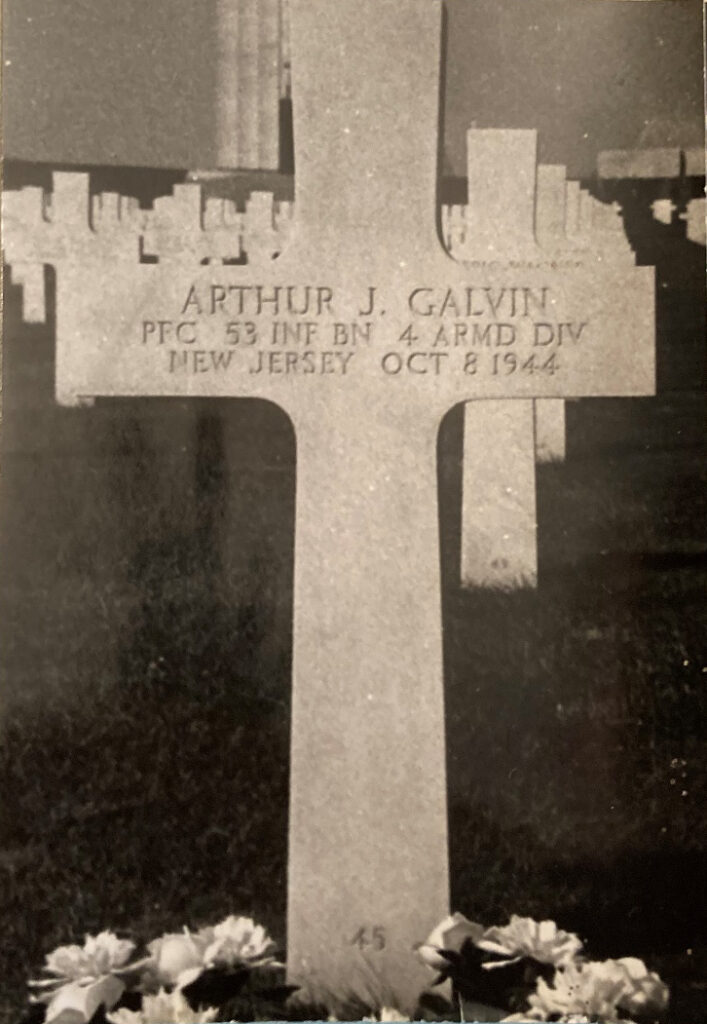

After surviving such a firefight for more than a month, we can imagine that Arthur Galvin was relieved to be alive. But sadly, just about one week later, he died. There are conflicting reports as to the manner in which his death occurred. His obituary simply said that he was killed in action near Metz, France. In his father’s retirement article, it stated that Arthur died in action at the Battle of the Bulge. Upon further research we discovered a handwritten letter filed at the Cranford Historical Society which indicates that Arthur died of a gunshot wound. His official military record from the Army archives stated that he died on October 8th, 1944, while in Juvrecourt, just 3 miles from Arracourt. Cause of death was an injury to the thorax, resulting from an exploding artillery shell. The record also stated that the wound was not battle related. In his last letter home, Arthur said they were sitting in slit trenches in a sea of mud. The 53rd Regiment Armored Infantry Battalion seemingly, was still in a defensive stand, waiting for fuel needed to attack Germany across the Rhine River, which they were eventually able to do. Now knowing what General Patton felt about slit trenches and being in a defensive stand, we know he was not happy about the state that the 3rd Army was in at this particular time. A letter to Arthur’s mother Minnie Wesighan Galvin was also found at the Cranford Historical Society. It was from Arthur’s best friend, CPL Lester Emmet Lott. The two soldiers were together through their training at Pine Camp in NY and throughout the many conflicts in which they were involved. He wrote that they had travelled deep into France and that Arthur was “the best soldier” and they were under the “heaviest shell fire.” He ended his note saying, “your son is a hero”.

The Cranford 86 team will continue to seek out the details on how this highly trained soldier lost his life while in the service of our country. He left the comforts of home in Cranford to answer the call of duty and deserves to have his complete story told. Arthur was survived by his wife Ruth and his mother and father. At the time of Arthur’s death his father had recently retired from the police department and was working at the Cranford Post Office. Arthur also left behind two sisters, Mrs. Anne Preuss of Cranford and Mrs. Edna Parsell of Westfield. While researching and writing this story we were lucky enough to be in contact with Edna’s son John Parsell and his wife Rose, now living in Brick, New Jersey. They were able to provide input from the military memorabilia that they have from Arthur’s life which includes a stack of letters sent home that were received throughout his years of service. Arthur was buried at Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France and remains there to this day. He would have been 30 years old on November 26, 1944. Arthur Galvin was the 26th of 54 Cranford men who lost their lives while serving in WWII.

Special thanks go out to Arthur Kennedy and Jennifer Goodwin who sponsored the banners of Arthur Galvin. Arthur Kennedy is a second-generation Cranford postal manager and Jennifer Goodwin has been the face of the Cranford Post Office service window that most every Cranford resident has visited. Thanks also to Sgt. Steve D’Ambola of the Cranford P.B.A. for also requesting the sponsorship of Arthur Galvin. After informing Steve that PFC Galvin was no longer available, the P.B.A. selected another hero, we are grateful for that.

PFC Arthur James Galvin’s banner will be dedicated at the Cranford Memorial Day ceremony that follows the annual Memorial Day Parade. The members of the Pruess and Parsell families hope to join us there and we invite all of our readers to attend as well. If anyone has any information regarding any of the Cranford 86 or their family members, we urge you to contact us at info@cranford86.org. The Cranford 86 project is happy to announce that we have now officially joined the Cranford Historical Society as part of a 501C3 non-profit organization. Our project will still maintain its current team of four as we continue forth with our mission. Checks for donations and banner sponsorships should now be made payable to the Cranford Historical Society and in some cases now can be tax deductible.

This is the fire power that travelled with Arthur Galvin’s 53rd Armored Battalion. Separated into 3 brigades, a total of 1000 soldiers were supported by 53 Sherman Medium Tanks, 17 Stuart Light Tanks, 18 self-propelled 105 mm Howitzers and 36 Hellcat Tank Destroyers.