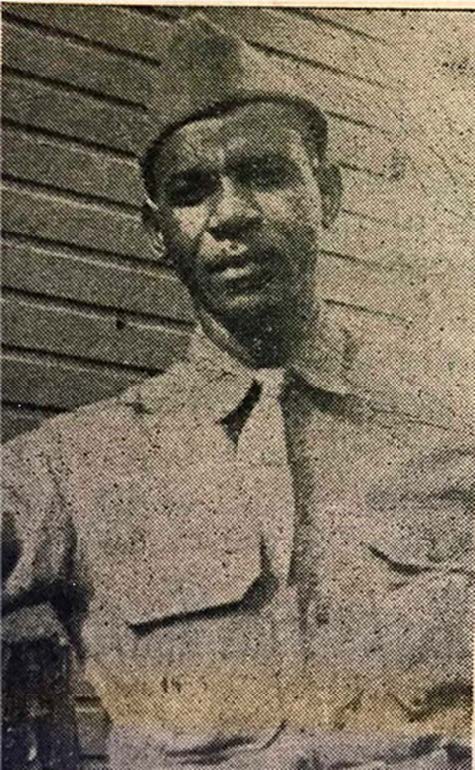

This is the only known photo of Sergeant William Henry Lee in uniform. It had been in the possession of the Cranford Historical Society and Cranford 86 was proud to share it with Sergeant Lee’s grandson.

In Honor of African American History Month

Meet Sergeant William Henry Lee, One of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, military proofreading by Vic Bary and editing by Janet Ashnault.

As the coordinator and lead writer of the Cranford 86 project, I regularly receive inquiries and requests for information in regard to many of the 86 servicemen on Cranford’s honor roll. Shortly after our project’s inception, I received a correspondence from Pastor William Lee III of Georgia, grandson and namesake of Sergeant William Lee, one of our Cranford 86 heroes. Sergeant Lee, an African American, died serving during World War II while in the Army Air Force (AAF). Pastor Lee was inquiring as to any information that Cranford 86 may have about his grandfather. Our team responded and we have been in contact with the pastor ever since. With Sergeant Lee’s story being so tightly linked to the African American struggles to achieve civil rights, we have been trying for the past two years to profile his story during February in honor of African American History Month. It was for lack of sufficient details that we missed the last two February deadlines. Finally, the work of our researcher Stu Rosenthal uncovered some new facts that were deemed relevant to notable historic and social events and with that, we decided that William Lee’s story was ready to be told.

At Hillside Cemetery in Scotch Plains, we found the limestone, government issued gravestone of Sergeant William H. Lee. The stone has weathered in the 75 years that have passed since his death. Much of the engraved lettering is worn off and the stone has sunk 10 inches into the ground. The date of birth on the stone is questionable. According to census records from April 1910, we feel that William’s actual birthdate is March 10, 1909.

William Henry Lee, the youngest of nine children, was born in Farmville, Virginia, likely on March 9th, 1909. His parents were York Lee, a laborer in a tobacco factory, and Cora Lee, a private cook. Both parents were born right after the conclusion of the American Civil War, and therefore were among the first freeborn African Americans in the former Confederacy. This would be the first connection to the civil rights timeline which would run through William’s life story. By 1915, William’s mom Cora and his grandmother Martha Booker, a freed slave, with at least 3 of William’s siblings, had moved to Cranford. They first set up home at 312 North Avenue E. and then later moved to 27 Burnside Avenue. The family became active members of the First Baptist Church at 100 High Street, where William’s brothers were part of the gospel choir. William’s oldest brother Benjamin, age 24, entered World War I in August of 1918 and served in the all Black 536th Engineer Service Battalion. Census records tell us that in 1920, William was still in Virginia with his dad. He attended Bridge Street High School there and it wasn’t until 1928 that nineteen-year-old William moved to Cranford. He became an electrician’s helper, living with his mom and his brother Joseph, a chauffeur, and his sister Virginia. At the time, Virginia was a seamstress, but later became a nurse. His other older siblings had by then moved to Patchogue, Long Island.

It was in 1930, that William would fall in love and marry Bertha Bouknight and have a child, Grace Evelyn. They would set up house at 10 Elise Street, Cranford and in 1932 have a second child, William Jr. William Sr. was now employed at Progress Cleaners on South Avenue as a clothing press operator and tailor. His family said that it was a perfect job for William because he would never be seen in anything but neatly pressed clothing. Sadly, in April 1940, census reports tell us that William Sr. and his wife had divorced, and he was now living with a friend at 31 Elise Street, just a block from Bertha and their children. We have been told that Elise Street was once lined with attached row homes which were destroyed by fire in the 1960s. Today, the corner of South Avenue and Elise Street, the site of the former row homes, still sits undeveloped and the house at #31 is currently empty and appears to be slated for demolition.

William Lee married Bertha Bouknight in 1932. They had two children, Grace Evelyn and William Jr.

As the country was trying to recover from the Great Depression, most did not realize that US participation in WWII was truly on the horizon. At the same time, within our US military itself, another conflict was brewing. The situation involving racial injustice in the armed services, combined with a higher percentage of Black Americans being recruited, was becoming volatile.

The Army War College Guidelines from WWI, a report written in 1917, referenced the problems of mixing African Americans with White soldiers. It stated that Black soldiers were liabilities, rather than assets to the war effort and that they had little capacity for initiative. The conclusion of the report was that the only place for a Black soldier in the Army was in a service or pioneer unit. Pioneer units were infantry laborers who did many tough jobs, one of which was collecting the bodies of fallen soldiers from battlefields and performing burial services. Another was “going ahead of advancing troops clearing the routes as necessary”. The report further stated, to maintain order, Black soldiers should be segregated from White soldiers.

Going into the 1930s, our military was guided heavily by the report, therefore, before 1938, the recruitment of African Americans was not encouraged. But, with a world war looming, the War Department formulated a new, grand plan to utilize the African American population to bolster our armed forces. Backed by the 1898 Supreme Court ruling of Plessy vs. Ferguson, which changed the interpretation of the 14th Amendment to make segregation legal again, the armed forces would now segregate the races of their entire populations. Using the premise of the ruling, that, if they provided “separate but equal” housing, messing and recreation, they were totally within the law to keep the races separated. It would seem that the Army worked harder on the “separate” and less on the “equal”. Most reports described the Black quarters and facilities as deplorable. The magnitude of what would be required to create separate spaces for the races could be better understood by examining the numbers. Between 1932 and 1939, the number of African Americans in the US military was a yearly average of about 2,000. From 1939 to 1944 that number would grow to over 500,000 at its height.

In 1942, the War Department, now having targeted part of their recruitment campaign towards Black Americans, specifically advertised a good wage to “negro soldiers”. Perhaps he was influenced by the recruitment initiative or possibly by his brother’s service in WWI, but ten months after the United States was plunged into WWII, William Henry Lee bravely stepped up to serve our country. On September 29th, 1942, 33-year-old, 5-foot 9-inch, 136 pound, William Lee walked into the US Armed Forces recruiting offices on Broad Street in Newark and enlisted into the Army for the duration of the war. That October he was shipped out for training to MacDill Airfield on Tampa Bay, in Florida. In this era, Black soldiers from the northern US that were sent to the Deep South would not be accustomed to the blatant racism and segregation that was present there. It was a difficult situation described in detail in a book found by Stu Rosenthal, Blacks in The Army Airforce during World War II, by Alan Osur. The author describes an indoctrination that our Cranford 86 hero may have experienced upon his arrival at his new Army home and it would set the stage for the change in culture he was about to encounter in the Jim Crow south.

Central Avenue in Tampa Florida, the only area in town where Black soldiers were allowed to socialize. It was the musical and cultural center of Tampa, much as Harlem was to African Americans in New York. Today it is a park and an engraved sign tells of the history of the African American business district that once thrived there.

See the YouTube video: Tampa Technique: Rise, Demise, and Remembrance of Central Avenue.

“A black enlisted man reported that when his unit arrived in Tampa for stationing at MacDill Field, their train was met by ‘this big rednecked sheriff’ who told them that there was only one place for them to socialize and that was along Central Avenue. He then introduced a local ‘good n*****r’, who instructed the black soldiers on the proper way to act while in Tampa.”

Despite this atmosphere, William’s leadership qualities must have been recognized immediately as he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant in just three months.

Coincidentally, William Lee was not the only Cranford kid at MacDill Airfield in 1942. 1st LT Alan Okell, whose story was featured in 2019, was transferred to MacDill in the summer of 1942. Tragic training accidents with the B-26 bombers were plaguing the commanders of the base as they were losing “One a day into Tampa Bay”. What we now realize was that crashing planes with the loss of several full flight crews was not the only problem happening at MacDill. This base would become the epicenter of a movement that would alter US military forces forever. We could be certain that our two Cranford heroes never met each other in Tampa. Although serving at the same base, it can be said that they were living in two entirely different worlds.

By the 1940’s, many Congressional mandates, prompted by public sentiment, were implemented requiring the Army to accept and utilize “Negro soldiers” into all sections of the Army in the same percentage of their numbers as compared to Whites, 10%. Some branches of the armed forces heeded the new regulations and accepted and properly assigned Black recruits. But many all but ignored the orders and still placed Black soldiers into laborious janitorial, transportation, food preparation and other unpopular service positions, just as had always been done. Citing objections and individual reasons the units were in many cases allowed to maintain their status quo. The AAF units were the last branch to accept the African American, insinuating lack of intelligence represented by low mathematics test scores. The African American cadets stationed at MacDill were placed in all Black units that would repair holes in runways, mow lawns and clean toilets. It was clear to these soldiers that the Black men were doing the undesirable jobs, while the White men were flying the planes. Frustrations were soon transformed into anger, resulting in bad morale and clashes between the races. The pretext of using segregation to keep order within the military was proving to be a failure.

An advertisement from The Cranford Chronicle for William’s employer at the time of his enlistment in 1942.

In 1942, at about the time of William Lee’s arrival at MacDill, a movement was taking root called the Double V Campaign. It was started by thePittsburgh Courier, the nation’s most widely read Black newspaper. The first V represented victory against fascism abroad and the second V for victory against racism at home. The movement shed light on the contradictions between our efforts to fight for a democratic ideology worldwide and the racial inequities prevalent in our own country. The Double V Campaign applied pressure through social protests and stimulated Congressional awareness of the problems that racial discrimination within our armed forces was causing. President and Eleanor Roosevelt were staunch supporters of the movement.

Around the country the Congressional mandates were being met with different levels of acceptance depending on the commanding officers of the respective bases. Every officer commanding a Black unit was, without exception, a Southern White. It was felt that the Southern officers knew how to handle the Black soldier and knew the potential within them. Later in the 1940s, Black soldiers received commissions as officers of lieutenant and above. Unbelievably, a White soldier would not have to salute or be expected to follow a command from a Black ranking officer. The highest ranking African American soldier at MacDill in 1942, we believe was a Sergeant (T-4), William Lee’s rank.

Racial unrest in the communities surrounding the bases was another source of conflict for the soldiers of color. The inability to travel on public transportation or use public restrooms, restaurants or even water fountains that were designated “white only”, caused violent encounters with the law which were often never covered by local news outlets. Many conflicts resulted in beatings and even killings, with the perpetrators rarely pursued by law enforcement. Use of disparaging terms when referring to the Black soldiers was common.

Racial tensions came to a head in the summer of 1943. Race riots broke out in cities around the country, precursors of the riots of the 1960s. Major uprisings occurred at AAF bases in retaliation for the mistreatment of African American cadets. In May, the riots were at Bamber Bridge in England and in June and August at MacDill Airfield in Tampa Florida, Sergeant Lee’s base. We cannot document that William Lee was involved, but some evidence may point to that probability. First, as a Sergeant, he was among the highest ranking Black soldiers on base; second, he was a Northern soldier, said to be the most outraged at the lack of proper treatment; and third, at age 34, he was older than most, having enlisted late in life. So, he most likely had the respect of his younger enlisted comrades and would have felt the responsibility to support the movement.

31 Elise Street, William Lee’s last address in Cranford. He and his family lived in 3 different homes on Elise Street. Currently it is the last house standing on the street and seems slated for demolition.

A later uprising and riot at Freeman Field in Indiana was larger and more organized. Undoubtedly inspired by the MacDill riots, it brought national attention to the general failure of the AAF segregation quota policies of Black flying units and revealed the lack of commitment of some AAF leaders to implement War Department directives on racial matters. The military’s eventual response to these uprisings, paved the way for the aspiring African American aviators who were to follow. At the same time that civil rights protests were occurring on airbases home and abroad, the government had taken notice and began an experiment to aggressively train Black pilots at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, an all-Black college founded by Booker T. Washington. By war’s end, 992 pilots had graduated, half of whom flew over Europe and were responsible for 260 enemy kills. The Tuskegee Airmen, as they were called, would never lose a bomber to enemy fighters. The success of this program had a tremendous influence towards the desegregation of the armed forces in 1948.

By November 1943, Sergeant Lee was deployed. He was assigned to an AAF Radio Center in Britain, at a time when less than 1% of the Black enlisted force was attached to the Signal Corps. We theorize that Lee was placed in a select, skill-based position, undoubtedly due to the knowledge that he had acquired from his civilian trade as an electrician’s helper. Radiomen were responsible for transmitting and receiving radio signals and processing all forms of telecommunications through various transmission media on the battlefields. It was hard physical work that involved many outdoor tasks in bad weather. The living quarters were cold, damp and inferior compared to the White soldiers’ accommodations. Racial relations off-base in Britain were said to be a better situation with the general public being more accepting of the Black man. While he was still in a segregated army and Jim Crow rules had followed him to England, for the most part things were going well for Sergeant William Lee.

Sometime in the first half of 1944, Sergeant Lee was involved in a “camp accident”, injuring him badly. No details of the accident were available to us due to a fire in an Army archives facility in 1973. He was sent back to the United States to a string of Army hospitals for treatment and to recuperate, first at Halloran Hospital (later to become Willowbrook State School) in Staten Island and then to the 15th General Hospital at Fort Dix in NJ. On June 16th, 1944 he was honorably discharged, 21 months after his enlistment. Four months later, on October 7th, 1944, he died of pneumonia at the Castle Point Veterans Hospital in Wappingers Falls, NY. Sergeant Lee was buried with full military honors at Hillside Cemetery in Scotch Plains, NJ.

William Lee and his family were active members of The First Baptist Church on 100 High Street.

The WWI guidelines pertaining to African American soldiers, stated they should be used primarily as infantry laborers in the pioneer units. Sergeant William Henry Lee certainly did serve as a pioneer, but not in the role that the military had planned. This grandson of David Lee, a slave from Farmville, Virginia, became a pioneer for racial justice who helped to pave the way for millions of Black men and women to follow in his footsteps in the military and throughout life as US citizens. The description of a pioneer soldier’s job of “Going ahead of advancing troops, clearing the routes as necessary” had evolved into a prophecy for the civil rights movement of which William Lee was an integral part. He was an American patriot, one of our Cranford 86, and has earned our respect and gratitude.

A touching letter to Cranford 86 from grandson William H. Lee III gave us a perspective of the love and respect that the family has for their hero. In the letter, Pastor Lee told of the moment his grandmother Bertha showed him the image of his grandfather in uniform. He told us that he had never seen a Black man in an Army uniform before and it was the most amazing moment of his life. Pastor Lee has fond memories of his 10 years in Cranford. Happily, he never felt that his race had caused anyone to treat him differently from any other kid. As a boy he remembers decorating his bicycle on Memorial Day with red, white and blue crepe paper. He would ride through the streets of Cranford with American flags flying from his handlebars, never realizing that this was a day to honor his grandfather. The photo that had so impressed Pastor Lee as a child, unfortunately was destroyed in the fire on Elise Street. Since then, he has been searching in vain for a photo of his grandfather in uniform. Cranford 86 was so pleased to share with him an image of Sergeant William Henry Lee, from a photo which had been in the possession of the Cranford Historical Society. We are trying to encourage Pastor William Lee III to travel from his home in Georgia to join us on Memorial Day morning for the dedication of his grandfather’s street banner. We have invited him to deliver the closing blessing on that day. He is going to do his best to be there. Read the letter about his grandfather at Cranford86.org.

We would like to thank the firefighters from Cranford FMBA Local 37 for sponsoring Sergeant William Lee’s banner. To learn more about sponsoring a Cranford 86 hero or to donate to our cause, please visit our website, Cranford86.org, where you can read all of the profiles that have been written to date. We hope you will join us as well on Memorial Day morning, post-parade at 10:00 am, as we honor all of our 86 at Memorial Park.

See many YouTube links to related videos on Cranford86.org.

Video: The Tuskegee Experiment – Oral Histories from the Collection of The National WWII Museum

Video: Tampa Technique: Rise, Demise, and Remembrance of Central Avenue

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHZyTGGl3QA

Video: PBS special about Central Ave. Tampa

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-1vsj32zu8

Video: African Americans in Britain during WWII

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bbR8qDLAAk8

Video: Documentary that follows the plight of African American soldiers through WWII

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3rnCPeKBwg

Letter to William Henry Lee

My name is Pastor William Henry Lee III, I am the namesake of William Henry Lee Sr. This is my black history moment of my grandfather William Henry Lee Sr. William Henry Lee Sr. the son of York and Cora Lee and the grandson of David Lee (a slave) was born on June 6, 1910 in Prince Edward County, Farmville, Virginia. He lived his youth in a prevalent Jim Crow south. At a young age of 10 years old his mother Cora; Grandmother Martha Booker and his six siblings migrated to the small-town Cranford, NJ. They resided at 27 Burnside Ave, Cranford, NJ, Union County. William was left behind to stay with his father York Lee in Farmville. His father died and in 1928 William migrated to be with his family in Cranford, NJ. His family were members of First Baptist Church on 100 High Street in Cranford. There he and his brothers were part of a gospel singing group.

He was employed in 1929 as an electrician helper. His older brother Benjamin served in WWI, his brother Joseph was a chauffeur and his sister Virginia a seamstress later to become a nurse. Four of his siblings left NJ to live in Patchogue, Long Island. William married Bertha Franklin and on July 29, 1930 they gave birth to Grace Evelyn Lee. On October 1, 1940 William H. Lee Jr. was born. In April 1940, William divorced his wife Bertha. In 1941 he was employed at Progress Cleaners as a presser and tailor and moved to 27 Cranford Avenue. My first meeting with my grandfather was by way of a picture, my grandmother Bertha showed me at 8 years old. I never seen a black man in an Army uniform before, this was the most amazing moment in my life. When I saw that picture, I pictured a hero and a servant, of someone who loved his country and wanted to fight for his country.

My grandfather grew up in prevalent Jim Crow south and left to live up in a less prevalent Jim Crow town Cranford. The change in life must have made him feel like America was his country and encouraged him to join the armed forces. He enlisted September 29, 1942 as a Private in the US Army in Newark, NJ. William was one of the 1.2 million blacks that enlisted in the Army in World War II. He did his basic training at MacDill Field, Tampa Florida. There at the MacDill Field, William and so many other black soldiers were degraded and treated like lower class citizens. Black soldiers lived in segregated quarters and were referred as “boy” “spooks,” “gorillas,” and “monkeys” by their fellow cadets. Once again, he and others had to experience the ugliness of racism. The living quarters were inferior to white soldiers. Black soldiers had faced two dilemmas fighting Jim Crow Army laws and fighting against Hitler and his forces. They fought for America, but it didn’t save them from Jim Crow.

William was promoted from Private to T-4 Sargent and later assigned in England at the Radio Center, Army Air Force base. Radiomen were responsible for transmitting and receiving radio signals and processing all forms of telecommunications through various transmission media on the battlefields. A great deal of his work was maintaining the radios. It was hard, physical work, and the difficulty was not only the weather, but the Jim Crow laws. The living quarters were inferior, cold and damp. Black soldiers had to fight democracy abroad and at home. There were riots at a lot of the Army bases due to racism. My grandfather became very ill and came down with a severe case of pneumonia. He was shipped back to the states and confined to several Army hospitals. He was detained at Halloran Hospital in Staten Island NY, Fort Dix in NJ and Castle Point Hospital, NY.

On June 16, 1944 he was honorably discharged as T-4 Sargent after 21 months of enlisting. Sgt. William Henry Lee Sr. was my hero, I am grateful and honored of him because of his wholehearted co-operation and untiring efforts which demonstrated in every respect that he appreciated the privilege of wearing an US Army uniform and serving a great country. On October 7, 1944, Sgt. William H. Lee, went home to be with the Lord, at the Castle Point Hospital, Duchess County, NY. He was buried with honors at Hillside Cemetery, Scotch Plains, NJ.

Thank you, grandpa you make me, proud!