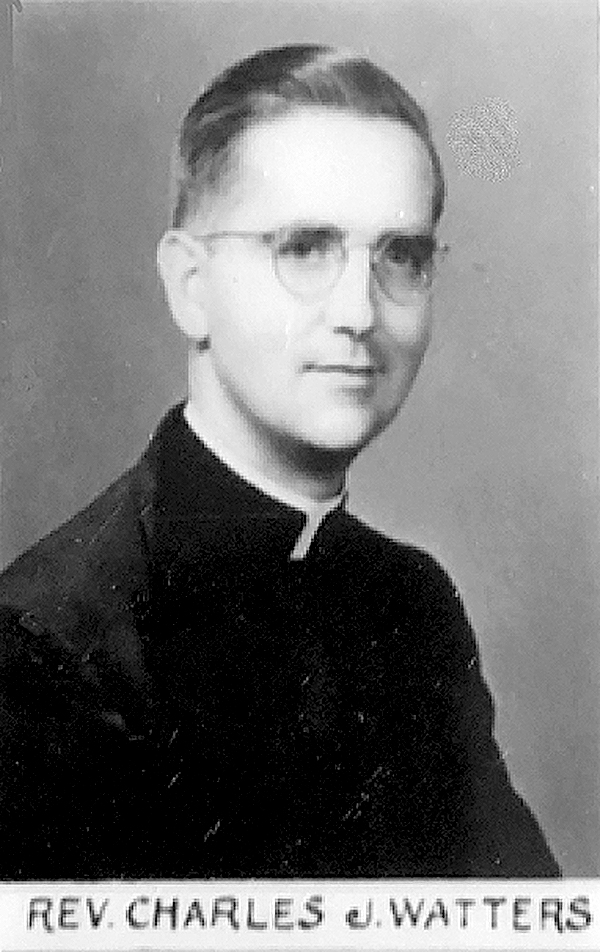

Graduation Portrait, Immaculate Conception Seminary, Darlington, NJ.

Meet Army Paratrooper Major Charles J. Watters, Chaplain 173rd Airborne Brigade A Vietnam War legend and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes

By Don Sweeney & Lt. Col. Steve Glazer (Ret.), Cranford Historical Society

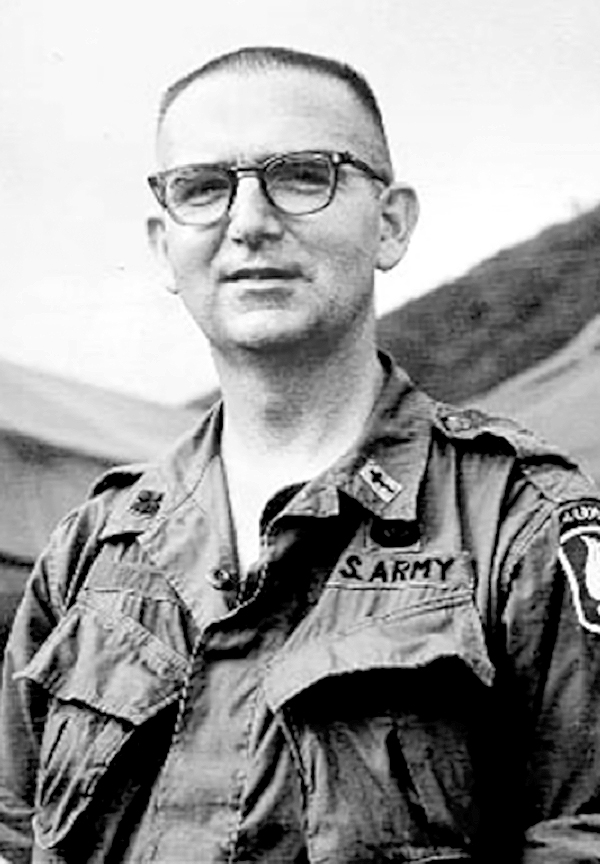

Fr. Charles J. Watters battlefield portrait.

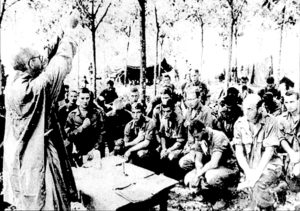

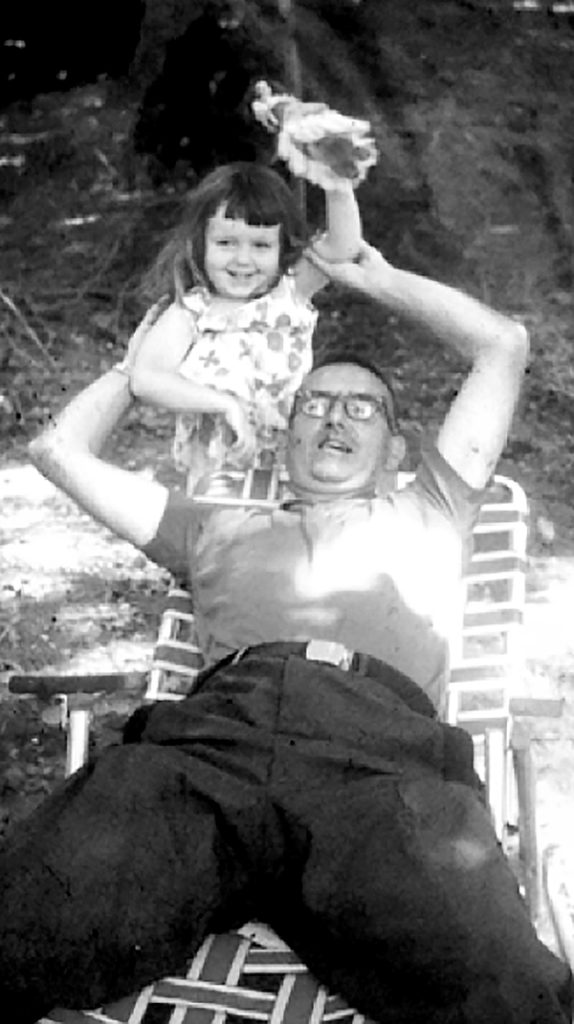

With the task at hand to reveal the next face and story of a Cranford 86 Hometown Hero, I leafed through our ever-expanding binder of research. A phone call from Ed Schmidt, a Korean War Veteran from Cranford VFW Post 335, called to our attention that November 19, 2017, was the 50th anniversary of the death of Father Charles J. Watters in Vietnam. To this point, we have been presenting lesser-known stories of our Hometown Heroes. Thanks to St. Michael’s Parish, which has erected a granite monument in front of the church, and to the Knights of Columbus, who operates a float in the Memorial Day Parade each year with members recreating the scene of his death, the story is not unknown to many in Cranford. Nevertheless, with such an anniversary, we decided to make Fr. Watters this month’s Hometown Hero. As in the past, there is always more to the story than we initially thought. This month was certainly no exception. I called my partner, Steve Glazer, as I do each month and told him our selection. He had preliminarily researched Father Watters and already had a stack of powerful documents, including some great pictures. He would resume his digging. By week’s end, my computer inbox was filled with detailed accounts of Fr. Watters’ life and military career. A poignant picture of a battlefield Mass being performed by Fr. Watters on November 19, 1967, the morning of his death, especially stood out. Steve also made contact with Donna Dey, Charles Watters’ niece. She was only 3 when her uncle had died. She would be a source of some insight to Charlie around his family. She told me that her father, Kenneth, the older brother of Fr. Watters, told her during one of the ceremonies to honor her uncle’s life that he would have hated such commemorations. He said his brother always said that he was no hero; he was just doing his job. She shared that the three brothers were a very quiet bunch, Uncle Charlie the quietest. A trip to St. Michael’s office provided a lead to retired Bishop Dominic Marconi, 90, a Seton Hall University and seminary classmate of Father Watters. I interviewed him at his home in Chatham. “Fr. Charlie,” as the bishop called him, attended 2 years of Seton Hall undergraduate studies before they both went to Immaculate Conception Seminary in Darlington, NJ, for 6 additional years of clergy training. The 1953 graduating class of 30 yielded three military chaplains and a bishop. They would gather for an annual reunion, where they would catch up on each other’s activities and have a few laughs. Bishop Marconi described Fr. Charlie as someone who listened more than he spoke. An affable man with a big heart, he recalls the last reunion Father Watters attended in 1967 between his two tours of wartime duty, when he volunteered for his second trip back to Vietnam. He still remembers Fr. Charlie telling him that he was needed there. That was the last time they saw each other. The bishop picked up a framed picture and handed it to me to keep. It was a fading color photo of the battlefield Mass offered by Father Watters on November 19, 1967, hours before he perished in service to God and man, all he ever wished to do in life. I will hang the picture at the VFW Post 335 mini-museum in Cranford. With a plethora of information and photographs in hand, I was feeling a little overwhelmed.

It was time to consolidate it all into a condensed story that would pay adequate homage to this brave, dedicated man. Charles Joseph Watters was born in Jersey City, NJ, on January 17, 1927. He graduated from Seton Hall Prep — then in South Orange — before being accepted to Seton Hall University. After his ordination as a Catholic priest in 1953, he served parishes in Jersey City, Rutherford, Paramus and finally, Cranford. An avid private pilot, his love of flying brought him in 1962 to the NJ Air National Guard, where he soon became their chaplain. With the nation’s escalation in Vietnam, Fr. Waters left St. Michael’s Church and volunteered in 1965 for active duty as a chaplain with the U.S. Army. At age 38, he successfully completed rigorous jump training, challenging to even much younger men, with the 101st Airborne in Kentucky, and was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the “Sky Soldiers.” By July 1966, then Captain Watters was in Vietnam, beginning his first tour of duty as a combat chaplain, during which he would earn the Air Medal and the Bronze Star Medal for Valor.

The late Rev. Charles says Mass for the 173rd Airborne Brigade in Vietnam just before he was killed.

Armed only with his camera, Fr. Watters didn’t hesitate to jump into a violent battlefield with the “Herd,” as the 173rd was sometimes called. When his unit was rotated to the rear for rest, he would stay in the field with the troops still facing imminent danger. Fr. Watters truly believed his duty was to remain alongside the soldiers doing the fighting. He would tend to both their physical and emotional needs by saying Mass, joking with them, providing spiritual comfort and tending to grievous wounds. The word quickly spread about the dedicated priest in the 173rd who routinely risked his life for his men. He sealed his legendary status on February 22, 1967, when he joined 845 fellow paratroopers in their jump during Operation Junction City, the largest such airborne assault of the war to that date, and the only major combat jump of the entire war. The intense three-month battle successfully rooted out a principal Viet Cong command center. In an interview in May 1967 after his safe return from battle, Fr. Watters was asked about his vulnerability under fire with no weapon. He answered with a smile. “I’m a peaceful kind. All I shoot is my camera. If they start shooting at me, I’d just yell “Tourist!” Seriously, a weapon weighs too much, and, after all, a priest’s job is taking care of the boys. But if we get overrun, I guess there will be plenty of weapons lying around to be picked up.” With his initial 12-month tour about to expire, Fr. Watters volunteered for another tour of duty, simply stating, “His boys needed him.” In November 1967, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) poured 7,000 plus troops into Dak To, determined to rid the Central Highlands of American Special Forces. An entire Green Beret unit was found dead in the area after being missing for 4 days. The U.S. presence there created a roadblock on the Ho Chi Minh trail, the North’s main supply route through Vietnam. The Americans reacted by launching Operation MacArthur. The 173rd, with 3,200 paratroopers, including Fr. Watters, would be making the assault into Dak To, known as the wildest terrain in all of Southeast Asia. Vietnam Magazine described it as a merciless land of steep limestone ridges, some as high as 4000 feet, with a tight web of jungle canopies that blocks daylight from penetrating on the brightest sunny day. It is laced with vines and thorns, and in it live diverse snakes, a million leeches and about half the mosquitoes in the world. Airborne assault was the only avenue of entry due to the hostile terrain. The enormity of the challenge would dwarf the previous Junction City operation.

The Memorial Day Parade float remembering Fr. Watters

The Battle of Dak To — November 3-23, 1967 — would be known as one of the fiercest fights of the Vietnam conflict. And the battle to take Hill 875 on November 19th was the most intense of the entire encounter. Securing Hill 875 would give the U.S. Army control of the region. We uncovered an official seven-page military report giving a powerful and detailed rendering of the fight, including Fr. Watters’ last moments of service. Sometimes overwhelming, it introduced the players of this “intense sustained fighting” one at a time and all of their parts in the battle, as well as the circumstances of their deaths. It must be read several times to grasp it. It gave me an eerie feeling similar to the one I received watching the recent PBS movie “Vietnam” by Ken Burns. Father Watters was with the 503rd Infantry, 2nd Battalion, Charlie Company, as they started the ascent to take Hill 875. He was given the option to stay behind, as many chaplains would do. He chose to stay with his boys, as he usually did when combat was likely. They would follow one of the steep ridges the area was known for. Delta Company to the left, Charlie on the right, Alpha Company would bring up the rear. Delta and Charlie companies quickly came under intense fire from what seemed to be invisible soldiers attacking from expertly camouflaged bunkers. By 3:00 p.m., Charlie Company was completely surrounded by 200-300 NVA regulars, with mortar rounds, automatic weapons fire and B-40 rockets continuously raining down on them. Throughout the day, Watters repeatedly risked his life to retrieve injured soldiers, even though it always meant leaving the relative safety of his own company’s perimeter. In one documented incident, a wounded paratrooper suffering from shock was standing in front of assaulting forces. Chaplain Watters ran forward without hesitation, ignoring numerous attempts to restrain him, picked up the man on his shoulders and carried him to safety. Futile attempts to resupply the company in this inaccessible area saw six helicopters shot down. Desperate calls for airstrikes were made as the sun set. One 500 lb. bomb dropped by a U.S. Marine fighter-bomber just arriving on station struck only 50 meters from Charlie Company, killing 25 NVA troops preparing for a night attack. Tragically, however, another 500 lb. bomb from the same aircraft struck the company’s command post and aid station. Some 42 Americans, many of them wounded already, were killed and 45 more were wounded in the war’s worst “friendly fire” incident. According to a survivor’s account, Fr. Watters was on his knees giving last rites to a dying paratrooper when the errant bomb hit, killing him instantly. The many men he saved that day never forgot Father Watters and neither did the Army. For his actions on Hill 875 he would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor, one of only seven such awards given to a chaplain in American history. This is the highest possible decoration awarded to United States military combatants. The official citation is available online and worth your efforts to obtain it. http://arlingtoncemetery.net/cwatters.htm Two days later, the remaining members of the 173rd Airborne Brigade would take and secure Hill 875. For their bravery and sacrifice they would receive the Presidential Unit Citation. During the 4-day engagement for the hill, 115 Americans were killed and 253 wounded. According to after-action reports, the Battle of Dak To yielded severe losses to American forces, with 376 dead and 1441 wounded. 40 helicopters and crews were also lost. NVA losses were estimated over 1450. So heavy were the NVA losses that their three participating regiments were not able to join the January 1968 Tet offensive, the Communists’ largest attack on U.S. and South Vietnamese forces.

The Meddal of Honor, America’s Highest Military Award.

The Communists ultimately failed in the offensive. For more history google Battle of Dak To. Major Charles Joseph Watters, Chaplain, age 40, was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, section 2-E. The Army Chaplain School in Fort Jackson, South Carolina, is named in his honor. An elementary school in his hometown, Jersey City, is named in his honor as well as a bridge on Route 3 in Rutherford. Major Charles Joseph Watters — “Father Charlie” — was a great American and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes. The goal of our group is to introduce the brave men who sacrificed all, so that we can live here in Freedom. This Memorial Day, at our town’s ceremony that follows our parade, we are planning to dedicate banners that will line the streets of Cranford. Each will bear the photographs and information of the Heroes whose stories have been told this year. To date we have introduced and told stories of 10 of our 86 Heroes, by Memorial Day we should have 15 or more. If you missed any you can find them all on Facebook at cranford86 or on Rennamedia.com in the archives section. If you have any comments or information about our project, I welcome your correspondences, Don Sweeney djsween@aol.com (908) 272-0876.

Exhausted soldiers of the 173rd Airborne after campaigning in the Central Highlands.

Uncle Charlie and Donna Dey.

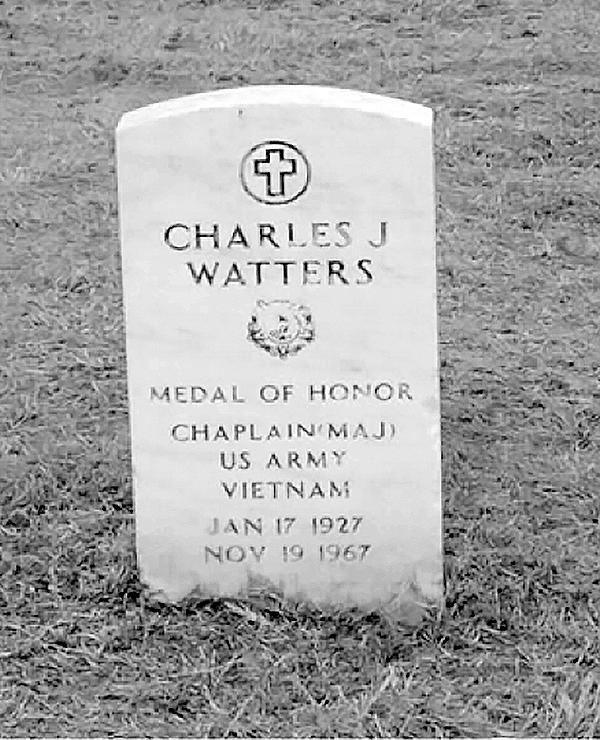

Arlington National Cemetery Grave marker at section 2-E

The granite monument at St. Michael’s