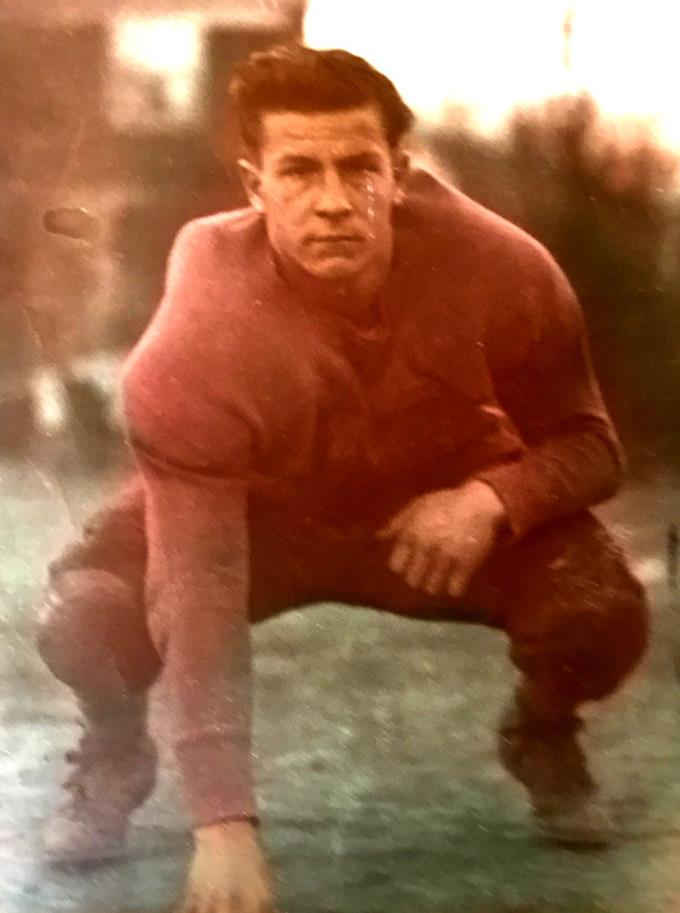

(above) Under his yearbook portrait Augie is called “Beer Barrel Augie”. It has been said that “barrel chested” was a physical characteristic of many of the D’Alessandris men. This picture of Augie posing in his new uniform beside their home at 10 Meeker Ave. may give a clue as to what exactly that means.

Meet Sergeant Augustine V. D’Alessandris, one of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, military proofreading by Vic Bary and editing by Janet Ashnault.

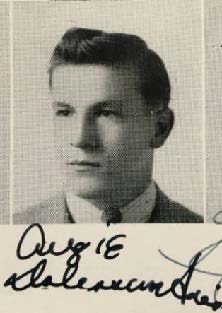

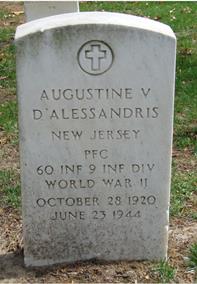

(above) In the senior section of the 1940 Cranford Yearbook, the Golden C, Augie signed his portrait for a friend. Here we found his nickname “Beer Barrel”, his aspiration for higher education and his senior quote which was very prophetic.

Recently our Cranford 86 team was wrapping up its third year of profiling our town’s Hometown Heroes. In the selection process that we do before each story, we review the research files of several candidates. As this was being done, from out of the blue, we received a phone call from Rosemarie D’Alessandris Boczon, the niece of Augustine “Augie” D’Alessandris. Rosemarie was made aware of our project by her son, who saw a Cranford 86 Facebook post last June, a D-Day tribute to their uncle. Although Augie’s story had been discussed several times since our project started, it was lack of detail and good photos that had prevented its completion. As always, we had hoped that someday, that all-important family connection would be found.

After a short conversation, I realized that Rosemarie was the link that we were missing in the Augie D’Alessandris story, a story long overdue to be told. Normally, our meetings with new-found family and friends of Cranford 86 members are held in person, over coffee. But being in the middle the Coronavirus pandemic and observing mandatory shelter-in-place and strict social distancing, we had to settle for a phone interview. Rosemarie had emailed us a stack of articles and pictures that she and her mother Minnie had gathered from years of research. With coffee cups in hand my co-writer /researcher Stu Rosenthal and I chatted with Rosemarie for over an hour about her dad’s legendary younger brother Augie, who died in WWII, three months after her birth. We could tell immediately from the emotion in her voice, that to their family, Augie was an iconic figure. We knew that what she was about to tell us was yet another heartfelt unveiling of a Cranford 86 Hometown Hero.

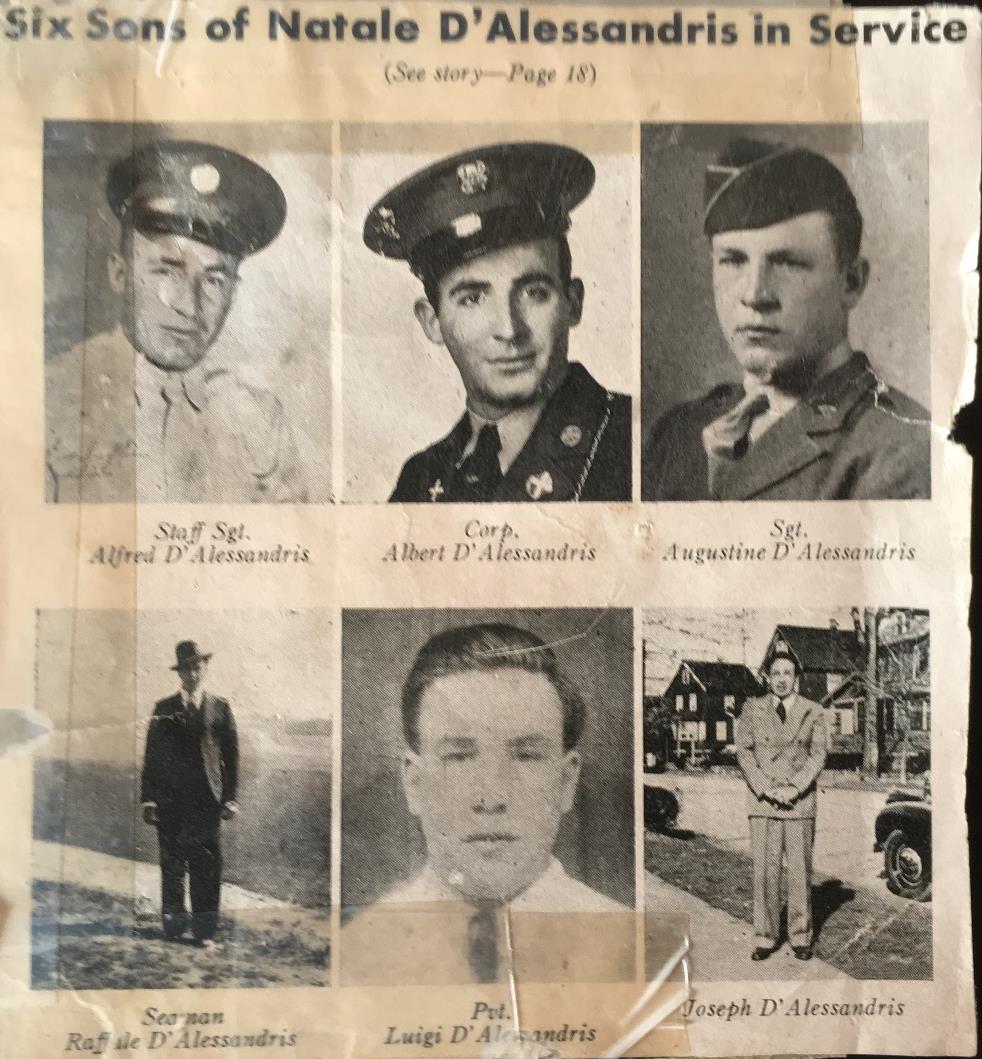

(above) The proudest parents in Cranford. In 1943, of their 10 children, Natale and Pietrina D’Alessandris had 5 of their sons serving in WW2, 3 of which were part of the D-Day invasion into Normandy, France.

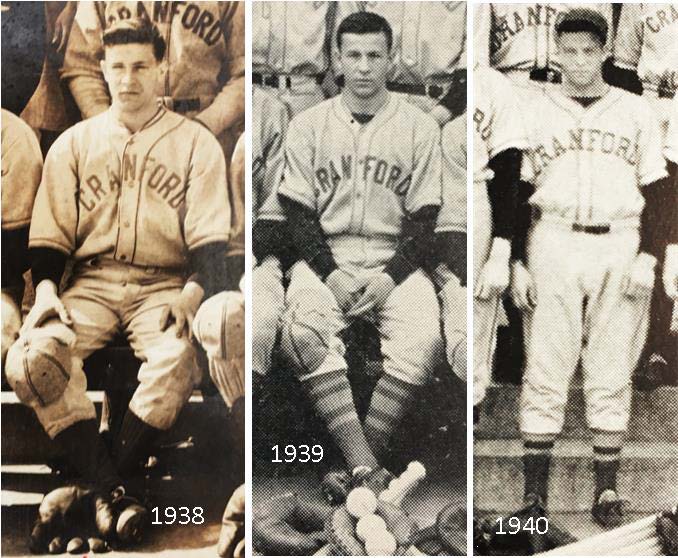

Augustine was born on October 28, 1920, the ninth of ten children of Natale and Pietrina D’Alessandris, of 10 Meeker Avenue. He attended Lincoln School before moving up to Cranford High School where he was found to be gifted academically as well as athletically. Although he played basketball for three years in high school, it was at varsity football as a center and at baseball that Augie D’Alessandris made his first mark as a hometown star. At 5’8”, 175 pounds, Augie’s most notable claim to fame was as the lead pitcher as well as the big bat in the lineup. On the baseball team’s page of his 1940 yearbook, it is insinuated that he was the jack-of-all-trades of the team. A humorous note there states: “Augie D’Alessandris also filled in as gardener while not pitching”. As the team captain, it was here that Augie first displayed his ability to lead, an attribute that would define him throughout the rest of his life.

To better understand the life of Augie D’Alessandris, it is important to realize the economics and history of the period in which he was raised. When Augie was nine years old the stock market crash of 1929 sent the country into the Great Depression, which lasted 10 years, ending the year he graduated high school. Although the text under his yearbook portrait indicated his future plans to be Seton Hall University, apparently that dream would have to wait until funds could be earned. Even though his father had steady work with the B&O Railroad, there were few depression families, especially a family with 10 children, that were financially prepared to send their children to college.

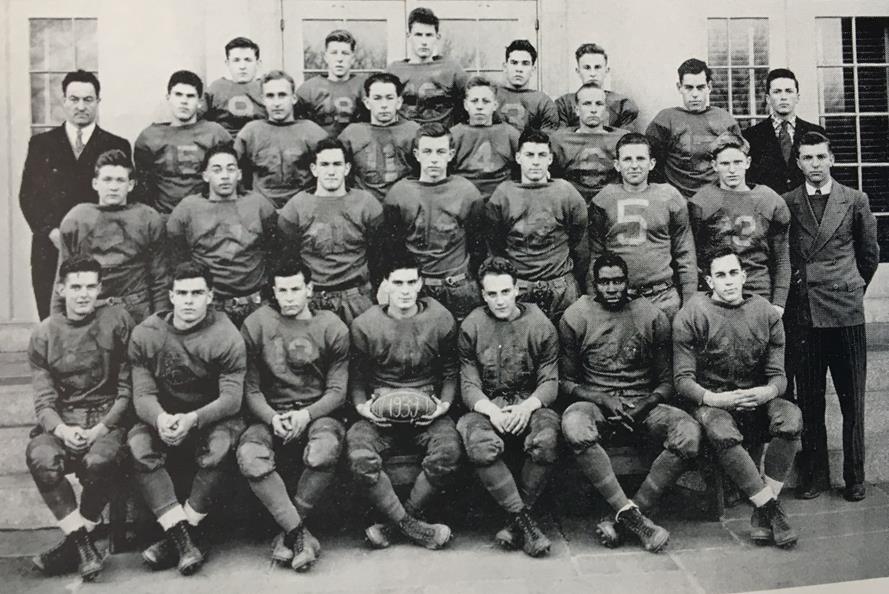

(above) As center on Cranford’s 1939-1940 varsity football team, at 5 foot 8, 175 pounds, Augie looks ready to take on his defensive opponents. Three years later he would find himself again on the frontline on the offense on another team, whose victory would change the world.

Following world history of the times, September 1939 was the beginning of WWII in Europe, when Hitler and the 3rd Reich started their Blitzkrieg attacks to seize Poland and then France. America, maintaining a strict isolationist stand, had us watching the events from the sidelines, only assisting Great Britain with some war supplies.

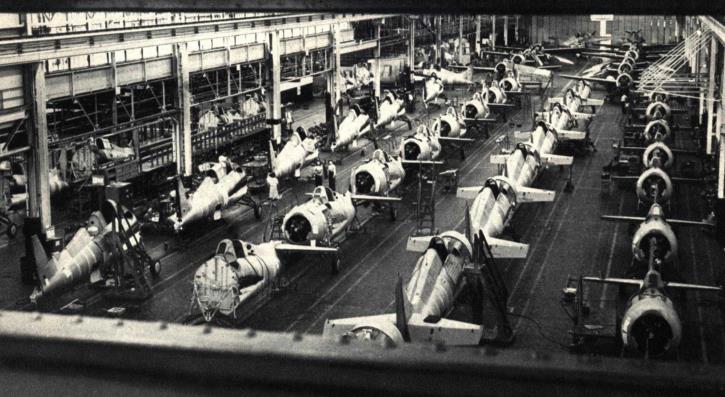

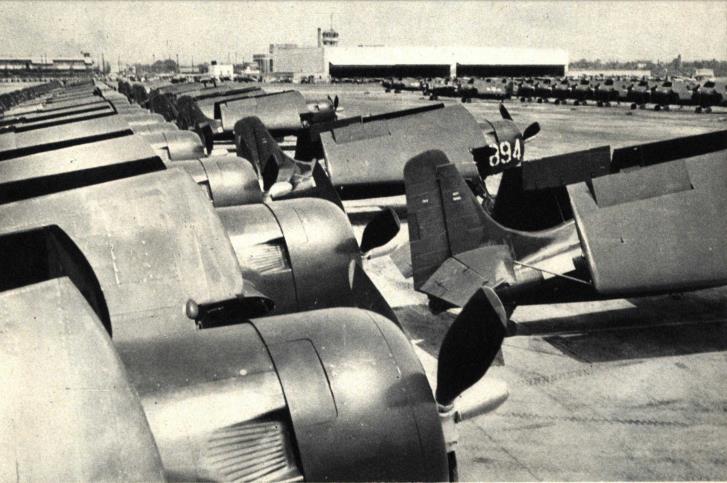

Rosemarie shared with us the strong work ethic that was taught by example in the D’Alessandris household. It was known in their family, that if you wanted something, you had to work for it. Rosemarie’s dad Rocco was Augie’s older brother. At age 31, Rocco was working at General Motors. Rocco vouched for his little brother and Augie was hired by GM in 1940 after high school graduation. This was good work for a depression kid. His physical condition and sharp intellect undoubtedly made him a valuable employee. Suddenly, Augie’s plans of working his way into college, like those of so many other young men, were put on hold when the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. Augie now found himself as part of the war effort as the General Motors plant in Linden was converted to become Eastern Aircraft. The plant began building the Grumman Wildcat, a carrier based, heavily armored, fighter bomber that would attempt to match the might of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero that was terrorizing our Navy over the South Pacific. Augie’s skills as an upholsterer of fine Buicks, Pontiacs and Oldsmobiles at General Motors’ most advanced assembly plant were now used to create cockpit interiors for hundreds of aeronautic fighting machines. He was now part of America’s infamous rapid manufacturing response which created the largest collection of war hardware in history. In 1941, the Linden plant was turning out one car per minute. By war’s end the joint efforts of Grumman and Eastern Aircraft would produce 35,000 planes from the assembly plants in Linden and Trenton, equaling more than a third of the 100,000 fighter planes created nationwide. Each evening the day’s productions were pushed by hand across a barricaded Route 1 to be test flown at a makeshift airstrip that would eventually become Linden Airport after war’s end.

Although he was already serving his country, Augustine V. D’Alessandris, like so many courageous Americans of his generation, recognized the existence of a greater need and took a valiant step. On June 13th, 1942, leaving the secure employment he had had since high school and the safety of his home in Cranford, Augie enlisted in the Army for the duration of the war plus 6 months. With he and his counterparts heading to the front lines, it was American women that then stepped up to fill the vacant positions in the factories. “Rosie the Riveter” became a common sight on the assembly lines at Eastern Aircraft.

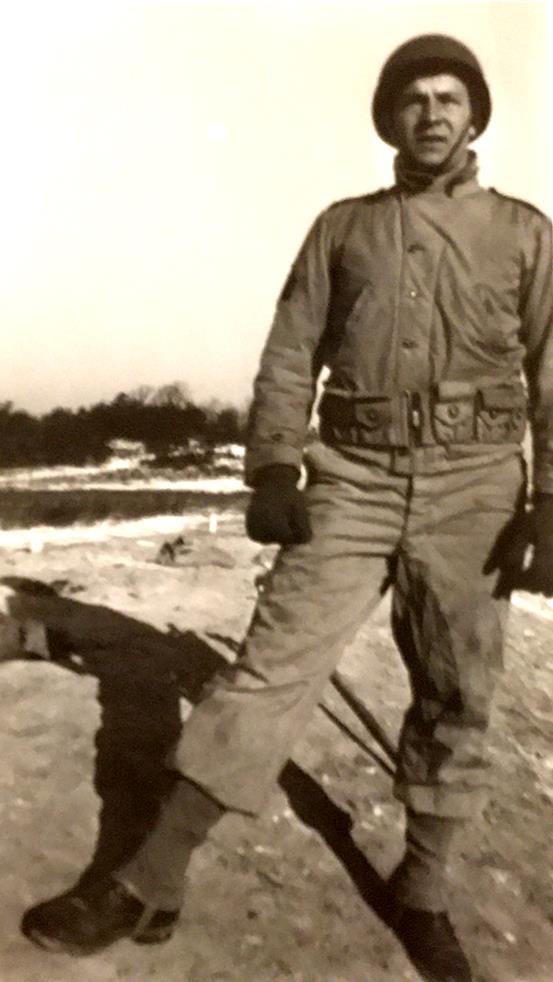

(above) Sergeant Augustine D’Alessandris, during what the family believes to be his pre-D-day training in England. A letter received by them during this time quotes him as saying,

“I love this stuff”.

After basic training at Camp Forrest in Tennessee, Augie travelled north to Fort Meade near Baltimore, for advanced training. As a training and staging facility, Fort Meade hosted 200 units and 3,500,000 soldiers throughout WWII. It was here, at Meade, that Augie’s leadership skills caught the attention of his superiors. In only three months from his enlistment date, he was promoted to sergeant, a somewhat unprecedented event. Augie continued training there until October 1943 and then shipped out to England joining the 9th Infantry Division, 60th Infantry Regiment. After successful tours in Sicily and Tunisia, the regiment was back for some rest and relaxation and to begin preparation for a secret mission. It was here, in London on February 25th, 1944 that Augie would meet up with his younger brother Louis. News of their meeting was published in the Cranford Citizen and Chronicle and provided great comfort to the family back home. Rosemarie shared with us that of all the five D’Alessandris brothers that were serving in the war at that time, it was Louis that everyone was concerned about, him being the youngest. Augie, the closest in age to Louis, communicated constantly with his youngest brother since entering the service. What no one had realized at the time was that four of the five D’Alessandris brothers were all in England that same day. And on D-Day, three of them would play a role in the invasion that would change the world.

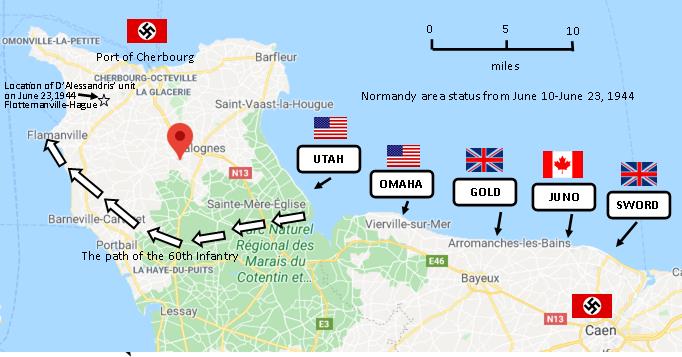

Augie and the 60th would join with the 4th, 9th and 79th Regiments for a force of over 6000. Their assignment would be to land on Utah Beach on D-Day +4, June 10, 1944 and traverse the heavily fortified Cotentin Peninsula in a grueling 15-18 mile trek through farms, countrysides and villages. The success of this mission would set the stage for the upcoming siege that would overtake the town of Cherbourg along with its deep-water port. Occupation of Cherbourg had been in the plans since the Invasion of Normandy (codename Operation Overlord) was conceived and was critical to the grand scheme of the Allied invasion of Western Europe. An amphibious landing onto the beaches of France had worked well for a surprise invasion of 156,000 men, accompanied by limited hardware. But to wage war to the degree that was to happen here, a commercial deep-water port was going to be needed. A few million men were to follow shortly along with all their needs for war. Ingenious artificial “Mulberry Harbors” had been temporarily created on Omaha and Arromanches beaches to allow large cargo ships to unload early supplies and armored vehicles, but a permanent port would be needed to supply what would become the world’s greatest invasion.

(above) A German concrete pillbox on the Cotentin Peninsula. Twenty of these forts guarded Cherbourg guarded Cherbourg from land attack. This embrasure, like many, was equipped an 88mm flat trajectory cannon, an “88”. The most effective anti-aircraft gun of its time, it came to be known as the anti-everything gun by the Allies. Its accuracy and speed of delivery made it the most feared offensive weapon of the war, excluding the atom bomb. Its addition to the pillboxes guarding Cherbourg is telling of the importance of the defense of the deep-port city. In the detailed report of the day of Augie’s death, it was reported that they were under attack from an 88.

Normandy was one of the three entry points that the Germans anticipated as potential portals for the expected upcoming Allied invasion. Hitler appointed Field Marshal Rommel to personally design and manage the defense construction of Cherbourg. Twenty enormous concrete forts known to the soldiers as “pillboxes” were strategically placed and constructed there. Each one was armed with an assortment of automatic weapons and large caliber cannons. Hitler had declared Cherbourg to be a “Festung” (fortress), a designation everyone knew to mean that its defenders were to fight to the last man. The Germans knew that they could not and would not, lose Cherbourg. Generals Eisenhower and Montgomery felt differently, they surmised that if the Allies could cut off the port city from supply and retreat, and with offshore as well as aerial bombardment, that Cherbourg could be taken. Augie’s unit, Company A, 1st Battalion, 60th Regiment, a group of about 175 soldiers, flanked by 350 soldiers from Company B and C, trekked across the countryside, working from farm to farm, encountering heavy resistance for 10 days. Their task was to eliminate the defensive pillboxes to allow for the placement of the massive attacking forces to follow. On June 19th a violent hundred-year storm poured enormous quantities of rain on the countryside causing flooding of epic proportions, making this task even more incredible. It was on that day, that the inclement weather gave Augie a pause to write home. In the letter he asked his mom not to worry about him, obviously knowing his life was in danger.

Detailed accounts from Sergeant D’Alessandris’ unit, from the army archives, were given to us by Augie’s family. They told of the tactics used to take out the 20 formidable pillboxes: “Each unit developed a slow but relatively safe method of dealing with these fortifications. Artillery and dive bombers would be used to force the Germans into their concrete defenses. A light bombardment would keep them pinned down while the infantry advanced to within 400 yards of the pillbox. The infantry would then take over, pouring heavy fire into the embrasures, while combat engineers (Augie’s described position) worked their way around to the rear, blew the doors open and then threw explosives or smoke grenades into the pillbox”. No names were mentioned of the individual participants taking on the tasks, but the D’Alessandris family knew that Augie, with his natural leadership and physical abilities, was right in the middle of the action. Multiple Medals of Honor were earned during this march, many lives were lost. Rosemarie shared a line from a letter that the family has saved from 1944, which gives us an idea as to the fortitude that her uncle possessed. In the letter Augie spoke about his pre-D-Day training, saying “I really like this stuff”.

On June 21st their first objective had been accomplished. Two thousand troops had made it across the peninsula, Cherbourg had been cut off from supply and thousands of paratroopers and gliders full of troops now fortified the perimeter. The big guns of a naval task force sat off the coast ready for action, it was June 22nd. General Collins, the American commanding officer, now issued an ultimatum to German commander General Von Schlieben, to surrender or be crushed. Von Schlieben, under strict orders from Hitler to fight until the last soldier’s bullet had been fired, ignored the request. The onslaught began and continued through to the next day. On the 23rd, fighter planes from aircraft carriers approached the battlefield, flares to mark the troop’s placement were ignited to guide the bomb placement and protect the troops. With the high winds from the persistent storms, the smoke quickly blew away. Tragically, many friendly bombs were dropped prematurely on positions held by the 60th, causing many casualties. Rosemarie says some in her family feel that this may have been how Augie lost his life, as this is the recorded date of his death, although there was so much violent action that day, there is no way to know for sure. From this point, formerly classified minute to minute archive reports tell of a full day of continuous Allied offensives answered by German tank counter attacks. The accounts were filled with such detail, that they read like a movie script.

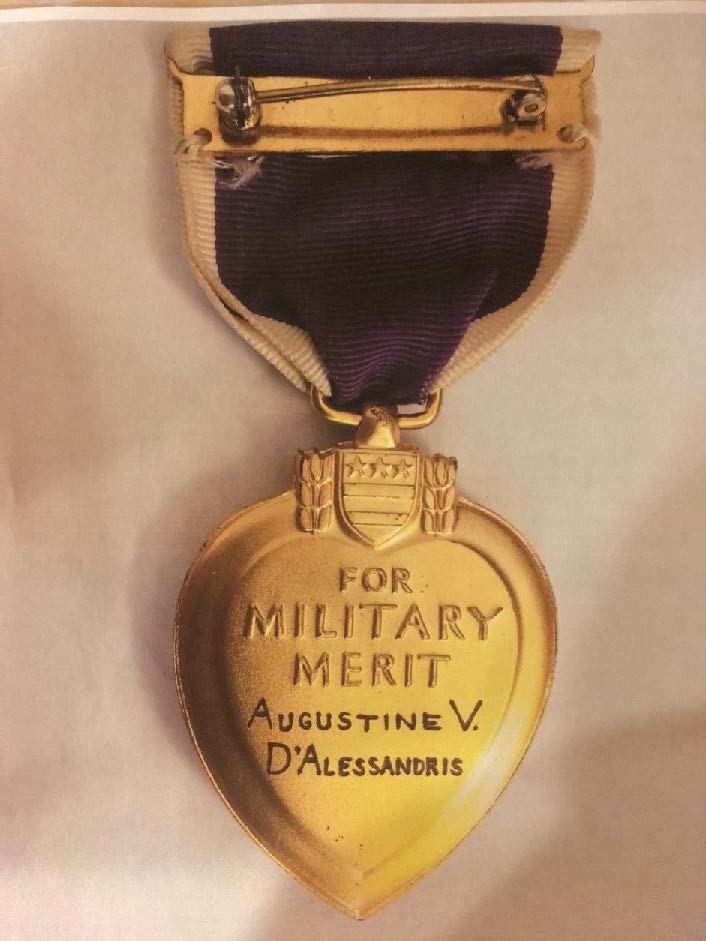

By June 24th the Germans’ main defenses had cracked. The fall of Cherbourg was now a foregone conclusion. General Von Schlieben directed all his demolition abilities toward the port. By the time he finally surrendered, he had inflicted so much damage that it would be September before the port of Cherbourg would receive the first ship full of supplies. When he received news of the surrender, an enraged Hitler chastised Von Schlieben as a coward. In total, 40,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner and 15,000 killed. Sergeant Augustine V. D’Alessandris was one of 2,800 Allied soldiers lost in what would be one of the greatest, yet bittersweet, victories of the war. In addition, 13,500 were wounded in the sixteen-day siege. It set the tone for the next year as the Allied forces would march across France and ultimately defeat fascism in Europe. Amazingly, a 45-mile underwater fuel pipeline across the English Channel to Cherbourg was operational by August, providing this most important supply to the war effort.

(above) A hand-lettered, customized Purple Heart presented to the D’Alessandris family after Augie’s death.

Back in Cranford a Western Union man arrived at the D’Alessandris home, bringing the tragic news from Normandy. It was the second such delivery to bring sad news to 10 Meeker Avenue. Only two months earlier, another telegram arrived stating that the B-17 bomber carrying their son, Technical Sergeant Alfred D’Alessandris, was missing over Germany. It was believed that he was being held as a prisoner of war

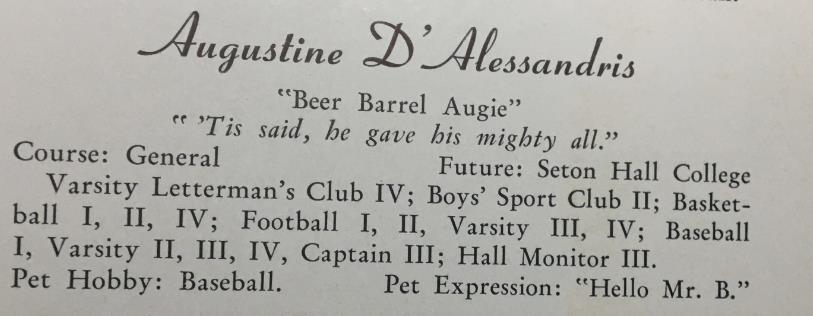

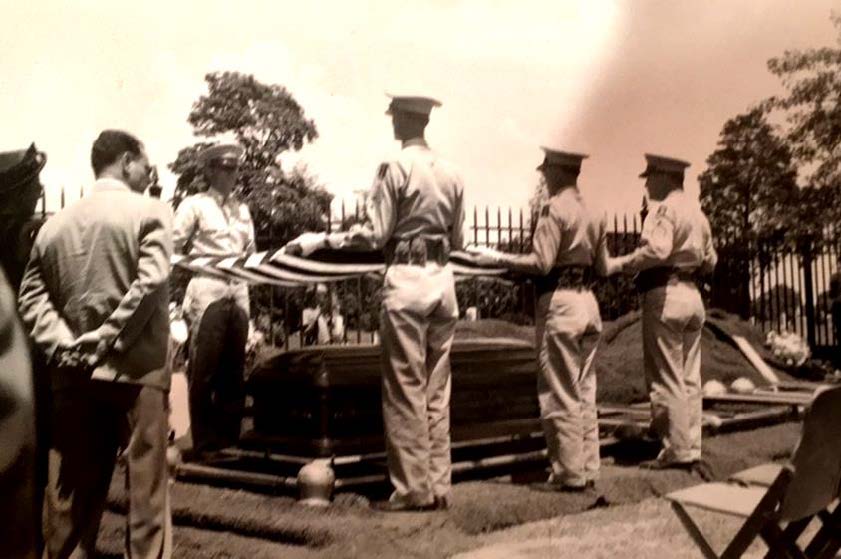

Augie was at first buried in France at Sainte Mere Englise Cemetery #2. In total, 14,000 American comrades were buried in three temporary American cemeteries there. In a massive repatriation program, two thirds of the servicemen were relocated to cemeteries chosen by their families back home in America. Five thousand families chose to have the remains of their loved ones remain in Normandy. They were moved to the Normandy American Cemetery on the elevated shore of Utah Beach at Colleville-Sur-Mer. On July 8, 1948 Augie was buried with full military honors at his final resting place at Beverly National Cemetery in Beverly, New Jersey. Rosemarie, although too young to attend, remembers her family’s stories of the event. A large turnout of Cranford townspeople attended the funeral in recognition of Augie’s life and his courage in the service to our country, as well as to support the family in the loss of their 23-year-old son and brother. Every member of the immediate D’Alessandris family was in attendance. Natale (72), Pietrina (60), Susanna “Suzzie” (40), Rocco “Rockie” (39), Raffaele “Ralph”(35), Amerigo “Matty” (34), Giuseppe “Joseph”(32), Alfredo “Alfred” (30), Alberto “Albert” (29), and Luigi “Louis” (25). Another child had died previously in 1911 at 3 months of age from whooping cough. His name was Agostino, yes “Augie”, named after Pietrina’s father.

Augie’s brother Alfred was liberated by the Americans after the historic “Long March” from the notorious German prisoner of war Stalag XVII-B in May of 1945, he had served as a top turret gunner /engineer on a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber with the 8th Army Air Force. Albert was a Corporal with the 82nd Airborne as a gliderman. With the 80th AA/AT, he was one of the first boots on the ground at Normandy on D-Day, as well as four other invasions including the famed Operation Market Garden. Ralph served with the Merchant Marines and lost an arm in an incident in the Pacific. Louie served for more than 2 years with the 29th Infantry, he landed onto Omaha Beach on D-Day and also served with a decorated unit at the Battle of St. Lo. Joseph joined the army but was released after 2 months with a bad leg.

Augie’s brother Alfred was liberated by the Americans after the historic “Long March” from the notorious German prisoner of war Stalag XVII-B in May of 1945, he had served as a top turret gunner /engineer on a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber with the 8th Army Air Force. Albert was a Corporal with the 82nd Airborne as a gliderman. With the 80th AA/AT, he was one of the first boots on the ground at Normandy on D-Day, as well as four other invasions including the famed Operation Market Garden. Ralph served with the Merchant Marines and lost an arm in an incident in the Pacific. Louie served for more than 2 years with the 29th Infantry, he landed onto Omaha Beach on D-Day and also served with a decorated unit at the Battle of St. Lo. Joseph joined the army but was released after 2 months with a bad leg.

The story of Natale D’Alessandris leaving the beautiful town of Patrica, Italy with his brother in 1901 is a tale of determination to achieve the American dream. Speaking no English, he immediately enrolled in night school and embraced his new language. He then attended railroad engineering classes and became skilled at laying railroad track. His natural intellect and ability to lead, allowed him to become a foreman incredibly quickly, traits that seemed to be passed on to his children. In 1907 at age 29 he returned to his hometown in Italy to marry his childhood love, Pietrina, 12 years his junior. Working then for the B&O/Staten Island Railroad he purchased a home at Cranford Junction, the railroad yard which sits at the corner of South and Lincoln Avenues near the Roselle border. He and his wife Pietrina loved America, and they instilled that love in every one of their 10 children. Throughout the war, a banner with five blue stars was prominently displayed in the living room window of their home, representing their five sons currently serving their chosen country. Their humble Italian American immigrant home was the proudest household in Cranford. Natale retired from the railroad after 47 years of service in 1947.

Sergeant Augustine Vincent D’Alessandris, a member of America’s Greatest Generation, answered the call to service when our country needed him most. He gave his life along with 56 other Cranford young citizens within a short four-year span. Although their names remain clearly etched in bronze at Memorial Park, as time has passed, their stories and faces have become blurred and have faded from view. It is the ongoing honor of our team, to one by one, reintroduce to you, each of these American heroes. In a timelessly prophetic way, Augie’s senior quote, from under his yearbook portrait, left me without words, “Tis said, he gave his mighty all”. Such can be said for all of Cranford’s 86.

To see all the stories and faces revealed to date, please visit our website at Cranford86.org or our Facebook page at Cranford86. The complete 110-page full color book of the 27 profiles done so far is now available for a donation that covers its printing cost of $35.00. For those that already have Volume 1 and 2, Volume 3 is also available now for $20.00. Contact us at info@cranford86.org. More photos as well as several YouTube video clips of historic newsreels of the period are also at Cranford86.org.

Special thanks go out to the Cranford Woman’s Club for sponsoring the banner of Augie D’Alessandris.

(above) On July 8th, 1948 Augie’s remains were returned to Beverly National cemetary in New Jersey. He was buried there with full military honors.

(above) A local newspaper article of the day highlighting the contributions of the D’Alessandris family during World War 2.

(above) As the premier pitcher and strongest bat in the line-up, Augie D’Alessandris was the jack-of-all-trades on the Cranford Va rsity baseball team for three years. Elected team captain in his Junior year, his leadership skills served him well in the Army, making Sergeant in only 3 months.

(above) The 60th Infantry Regiment of the 9th Infantry, D’Alessandris’ unit, travelled across the Cotentin Peninsula to cut off German supply lines and stop any possible retreat. The arrows, although not exactly accurate, show the unit’s path taken from Utah beach.

(above) Assembly lines at Linden’s Eastern Aircraft, formerly General Motors, formerly General Motors. 35,000 Wildcats and Avengers were assembled in Linden and Trenton by 1945.

(above) Newly assembled Wildcat FM-1 aircraft sit on the tarmac at the airfield that would become Linden Airport. In the background is the newly erected hangar with control tower which sat on Route 1 across the highway from General Motors. Augie worked at GM during its conversion from cars to airplanes.

(above) The 1940 Cranford HS yearbook football team photo.

(above) The D’Alessandris home on at 10 Meeker Avenue as it looks today. In 1944, on the side of the house was a regulation bocce court. Interestingly, one side of the court was inside the garage, allowing play to commence even in inclement weather. The backyard was a relatively large family farm that was on property not actually owned by the family. Today the backyard is the Cranford Senior Housing on Lincoln Ave. A large variety of produce was grown there which included rows of grapevines on trellises. Much of the produce was canned for year-round consumption. The grapes were harvested and converted into homemade wine that was known to be stronger than the average store-bought vintages.

YouTube Video: Nat Geo ”D Day Sacrifice” 2014 Battle of

Explains the need to overtake Cherbourg and lead up to its siege.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-roIU8I7T-M

YouTube Video: The Mulberry Harbor

The strategic importance of Cherbourg and the Mulberry Ports.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWO5wpZGG14

YouTube Video: Factory-Made Invasion Harbor (1944)

More about the Mulberry Ports.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Utlg3Zjyyuc

YouTube Video: The Road To Cherbourg (1944)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJPmwjUjfGk

YouTube Video: Squeezing Nazis Out of Normandy (1944)

Shows the type fighting in French farmhouses and villages.