(above) Juan Bargos leaning on a Ford Model T, between 1909 and 1918.

Meet Corporal Juan Bargos, one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of Armistice Day

By Don Sweeney, Stu Rosenthal Lt. Col. and Steven Glazer (ret.)

(above) As a member of Cranford Tennis Club as well as Elmora Country Club, Juan Bargos was a competitive Tennis player throughout his adult life.

The upcoming centennial of Armistice Day, which marked the end of fighting during World War One (WWI), turns our attention to the early citizens of Cranford who answered the country’s call to arms. The Cranford 86 timeline begins with 321 townspeople who were the first from Cranford to serve during wartime, fifteen of whom perished, including Juan Bargos. We previously profiled two of our WWI heroes — Newell Fiske and William Hale — inspired by records available at the Cranford Historic Society. But information about our other WWI fallen was scant, despite a trove of post-WWI materials assembled by the late historians Bob Fridlington and Lawrence Fuhro. We were originally intimidated by this lack of information and unsure we could properly profile Juan and his WWI brethren. But our researchers scoured untold sources to reveal Juan’s astonishing journey, despite personal tragedy and ill fate. We were newly encouraged about future Cranford 86 stories for all our WWI heroes.

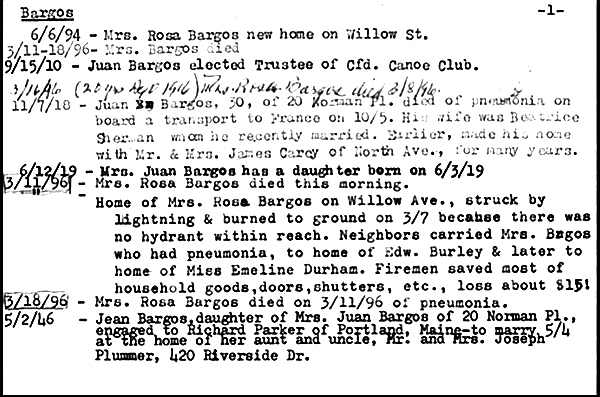

Juan Bargos was born on October 19th, 1888 in Mexico City, Mexico, and moved to the U.S. at a very early age with his widowed mother, Rosa Bargos. We picked up on Juan’s life in Cranford in 1894, when he and his mom moved into a new home on Willow Street. Tragedy soon befell the Bargos family when, on March 7, 1896, their house was struck by lightning and, owing to no nearby fire hydrant, it burned to the ground. Rosa Bargos had been suffering from pneumonia and was initially carried to the nearby home of Edward Burley, and then to the home of Emeline Dunham. Friends called on Ms. Bargos while infirmed at Emeline’s residence at 301 Orange Ave, but Rosa died four days later. Her funeral service was held at Emeline’s home, attended by the newly orphaned Juan.

Emeline Dunham, an active Presbyterian parishioner, was praised for caring for seven-year-old Juan and his mother during this traumatic period. Emeline was descended from the prominent Dunham family, which had settled a local farm and homestead in 1730. Following Rosa’s death, Juan took up residence with Emeline and her adopted daughter, Florence Peterson. Juan was informally adopted by Emeline, with whom he lived for many years into adulthood. Miss. Dunham appears to have fostered in Juan the stability and altruism that would safeguard his remaining childhood, and perhaps inspire him to later volunteer for military service.

At Cranford’s public schools, Juan was lauded for his singing and patriotic recitals. As an eighth grader at Grant School in Dec. 1902, he recited Longfellow’s Woods in Winter during the holiday concert, the words would prove to be prophetic of Juan’s life that would follow. Read them on Cranford86.org. For Decoration (Memorial) Day in May 1903, Juan sang for a Civil War veteran who had visited the school. During a school assembly in Feb. 1904, in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday, Juan recited the Gettysburg Address. Ironically, Juan would later train on the same battlefield in Gettysburg, PA near where President Lincoln spoke these famous words forty years prior.

Juan had a passion for athletics and excelled in sports as both a player and leader. He was a star pitcher at Cranford High School, but also an apt base runner unafraid to steal home plate. Juan was captain and goalie of the local hockey team and played halfback on the school football team. While just a freshman, Juan was voted president of the new Cranford High School Athletic Club. As a young adult, he was a star player at the Cranford Tennis Club and competed in canoe races on the Rahway River with the Cranford Canoe Club where he was elected Trustee. Juan also played broomball, a hockey-like game played with brooms on ice.

In 1918, Juan Bargos was trained in the new tank technology at Camp Colt, PA, commanded by a young Dwight D. Eisenhower. The future U.S. President and his wife adored the Gettysburg area and retired there in 1961following his presidency.

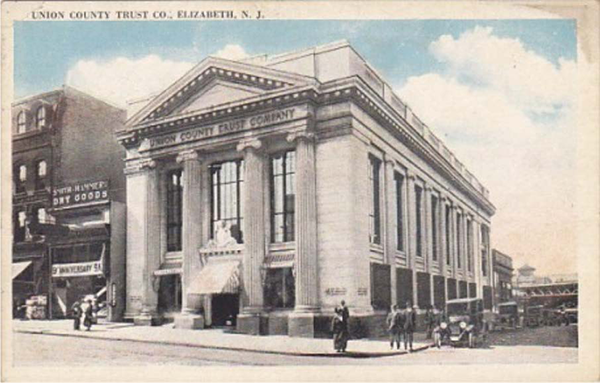

As a young man, Juan experienced a freak accident in July 1907 which presaged more heartbreak. He was a passenger on the Central Railroad of NJ, traveling from Cranford to Elizabeth, where he worked as a clerk at the Union County Trust Company. During the trip, Juan somehow pinched off three of his fingers from the door of the railroad car. Despite this injury, his tennis game did not appear diminished, nor would it disqualify him from military service.

In 1910, the adopted daughter of Emeline Dunham, Florence Peterson, with whom Juan had lived for many years, died at the age of 32 years following an extended illness. Florence’s death surely afflicted Emeline and unsettled the household balance now familiar to Juan for many years. Two years later, in December 1912, Emeline Dunham, the oldest native of Cranford, passed away at the age of 82. Cranford would later create Dunham Ave. in memory of Emeline, to recognize her volunteerism and outstanding citizenship.

Following Emeline’s death, Juan took a room at the home of Mr. and Mrs. James Carey of North Ave and continued at the Elizabeth bank. Following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914, Juan, along with several other Cranford men, volunteered for the Citizen Military Training Camp (CMTC), a summer military encampment designed to prepare for a war many believed would inevitably engross the United States. Juan was perhaps inspired by Newell Fiske, who had recently completed CMTC training, and was an early activist, inspiring young Cranford men to join. Juan attended the month-long training in Plattsburgh, N.Y., in the early summer of 1916.

(above) An avid canoer, Juan was elected Trustee of the Cranford Canoe Club in 1910

After CMTC training, Juan returned to Cranford, continued with his banking job and honed his tennis game. In July 1917, he was paired with Beatrice Sherman for a mixed doubles tennis tournament in nearby Elizabeth. By now, the U.S. had entered the war and several drafted men from Cranford were enjoying the remaining days of summer before they would depart for military training and the European battlefields. Juan had registered for the draft but was not selected. Yet, he must have felt the need to serve his adopted country since he volunteered for military service anyway.

Juan joined the U.S. Army and arrived at Fort Slocum, NY, near the city of New Rochelle, for recruit processing and examinations on Apr 25, 1918. One week later, Private Bargos transferred to Camp Colt, which was located on historic Pickett’s Charge battlefield in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Led by future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the camp had been transformed into the first U.S. training facility for tank warfare. In his first command assignment as a young officer, Eisenhower’s mandate was to assemble and lead a unit of volunteers to train on tanks, thereby ushering in the modern era of the U.S. armored forces.

(above) A family picture on Juan and Beatrice’s wedding day. Juan is at the top right and his bride is at the bottom right. Beatrice was the Vice President and manager at Real Strong Coal Co. in Cranford for 40 years.

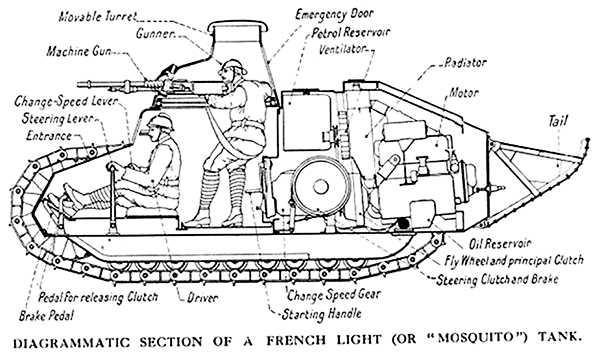

Camp Colt was ill-equipped and void of any tanks when Bargos reported for duty. Nevertheless, Juan was assigned to Company ‘C’ of the 327th light tank battalion and was trained in basic drill. The men improvised tank operations by attaching machine guns to flatbed trucks and assembled car chassis made to look like tanks. They played competitive sports, where Juan probably stood out among his peers.

After just five weeks of military training, Juan was promoted to Private First Class. He was granted leave and returned to Cranford where he married Beatrice Sherman, his former doubles tennis partner, on June 5th, at her home on Norman Place. The newlyweds enjoyed a brief honeymoon before he reported back to Camp Colt and encountered his first tank. The Renault FT-17 tank had just arrived in Gettysburg, and the curious residents turned out to see the peculiar vehicle as it chugged along the streets, kicked up dust and sputtered with exhaust. Additional tanks were soon delivered from France.

The Tank Corps volunteers at Camp Colt included alien residents who yearned for U.S. citizenship. This included Juan who had previously declared his intent for citizenship on his draft registration card. During the war, lawmakers simplified the naturalization process for aliens serving in the armed forces, often through special court sessions convened at military camps. We know of multiple such courts convened by the Adams County, PA clerks in mid-1918, when several hundred trainees were naturalized in a YMCA tent outside of Camp Colt. We believe Juan Bargos was among those soldiers granted U.S. citizenship in an early session but were unable to confirm his naturalization as of this writing.

Beginning in July 1918, thousands of Camp Colt soldiers, including Juan’s 327th battalion, were moved to Fort Tobyhanna in the Pocono Mountains, Northeastern Pennsylvania. The site provided a larger acreage for tank training. Its lack of treasured national war monuments, unlike the Civil War battlefields encompassing Camp Colt, also allowed for live fire training exercises. We believe Juan remained at Fort Tobyhanna through mid-September, culminating in his promotion to Corporal on September 11th. As a qualified tank driver, Juan was in transition again after nearly five months of training.

(above) A noble Juan Bargos as was depicted in a 1918 Elizabeth Daily Journal story about his death.

None of our research reveals Juan’s exact whereabouts in mid-September 1918, or right before his fateful journey across the Atlantic. However, we are fairly confident Juan shared precious, albeit fleeting moments with his new wife, Beatrice. She subsequently gave birth to their daughter, Jean Bargos, nine months later, on June 6th, 1919. It is unlikely Juan ever knew his wife was pregnant.

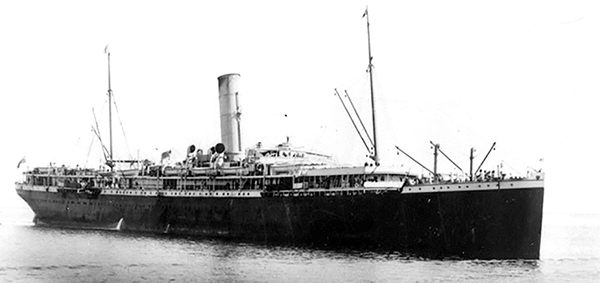

Juan’s battalion was among 1,836 troops crowded aboard the SS Orontes, beginning Sep 24th, awaiting departure from the 56th Street pier in New York Harbor. Juan’s vessel was part of a vast convoy, the HX-50, comprising 12 ships hosting at least 20,000 American soldiers bound for the west coast of England. They would travel the submarine-infested Atlantic waters, guarded by six destroyers, a battleship, a dirigible and several sea planes. But the military planners had miscalculated the real threat, which was microscopic compared to the formidable German U-boats.

Aboard the SS Orontes was a delegation of newspaper reporters invited to visit the Allied Western Front. One reporter, E. Lansing Ray, kept a daily journal of detailed notes. According to his early entries, the SS Orontes was dirty before it departed NY and 70 members from its prior crew had to be removed due to a contagion of Spanish Influenza, an H1N1 virus related to swine and avian flu. Yet, the ship departed NY on September 25th at 11:30 am, despite an official memo that same day from the Acting Surgeon General of the Army recommending that U.S. troop shipments overseas be temporarily halted for flu-infected organizations. The disregarded memo correctly surmised that overcrowded troop ships would endure thousands of influenza cases, and numerous deaths.

Mr. Ray’s log indicates that many soldiers aboard the Orontes were sickened by the second day of the voyage. The ship was at double its normal capacity and packed with civilian passengers housed four to a room. Soldiers teemed throughout its decks. By the third day, the sun yielded to stormy weather and the U-boat threat had receded. But the waves began breaking over the lower deck onto sleeping soldiers. The civilian passengers remained in their smoke-laden staterooms while the soldiers marched outside when they weren’t lying around on the drenched deck. By Sep 29th, the weather had turned much colder, thick fog brimmed and the seas surged with heavy swells. The Orontes and its convoy had steered directly into an Atlantic hurricane. Many aboard became critically ill with incessant coughing. Mr. Ray recorded the first death on Oct 1st, triggering a daily ritual of deaths and burials at sunrise. By October 6th, wind gusts of 80 mph generated mountainous waves that broke windows, flooded staterooms and injured passengers tossed from chairs. It was hardly a peaceful setting for burials at sea. The violent weather caused navigation problems, and the convoy flagship, HMS Otranto, crashed off the Irish coast, killing an estimated 470 men. Before the Orontes reached Liverpool on Oct 7th, at least 1000 were sickened and 25-30 men were lost to disease. Sadly, Juan died on Oct 5th, just two days before he would have reached England.

(above) A family snapshot of the newly widowed Beatrice Sherman Bargos and daughter Jean in front of their home at 20 Norman Place in the fall of 1919. Jean was born on June 6th, 1919. Eight months after Juan’s death.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919 affected one-third of the world population, and was considered the world’s deadliest natural disaster, killing an estimated 50-100 million people including 675,000 Americans. It sickened 20-40% of U.S. Army and Navy personnel and was responsible for more wartime deaths (57,460) than direct battle (50,280). Juan Bargos was among at least four Cranford service men believed lost to disease during WW1, including Fred Heins, Sidney Craig and George Haskins.

Captain Eisenhower (‘Ike’), to his chagrin, was never assigned to a combat position during WW1. The first tank brigade to see action in France was commanded by another young West Point graduate, a few years senior to Ike, Captain George S. Patton. While not as battlefield effective as planned, the Renault FT-17 tanks added an awe effect against the German enemy. There were reports of immediate retreat by enemy forces at just the sight of the rolling armored artillery. As in many of the new creations of engineering and manufacturing that initially appeared on the WW1 battlefields, there would be advancements and perfections that would appear some 20 years later, in the same battle theaters, that would change the outcome of a war that would save the world from fascism.

Beatrice Bargos never remarried and spent a career at Reel-Strong Coal Co. in Cranford, which remains in business today. She retired after 40 years as a Vice President. Their daughter, Jean, would marry and have two sons, Mat and Chris Parker, whom we located in Vermont and Pennsylvania, respectively. They supplied us with some of the photos displayed here, and the letter to Juan’s widow from his Commanding Officer. He described Juan as “a man of character, self-sacrificing and cheerful to the end, the life of his company, and dearly beloved by all, God saw fit to choose him, he was buried at sea with full military honors befitting the servant of his country which he was.”

The young Mexican boy who immigrated to America with his mother for a better life, lived a storybook existence, and overcame every other obstacle thrown his way. He made his mark on the country that claimed him as a genuine citizen in the end. Juan Bargos was an American hero and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes.

With gratitude to Sue Buontempo, a resident of Bargos Place in Cranford, for sponsoring the banner of this month’s hero. Please visit us at Cranford86.org for additional stories and contact us at info@Cranford86.org or (908) 272-0876 if you would like to donate to our project or purchase volume one of the bound stories from year one.

(above) Juan travelled among 1836 U.S. soldiers aboard The SS Orontes bound for Europe. It was a horrific trip, travelling through a category 2 hurricane and an outbreak of The Spanish Flu. Juan succumbed to the virus and died on board on October 5th, 1918 and was buried at sea with full military honors.

(above) A 1918 training exercise at Camp Colt in Gettysburg PA. The tank held two men and the platoon followed behind.

(above) This line drawing of the Renault FT-17 gives you a feeling of what the battlefield experience for a tanker might be like.

(above) A typical Burditt file card that is found at Cranford Public library. It catalogues every mention of anyone in The Cranford Chronicle or Citizen since the late 1800s. It is among our first sources when researching a Cranford 86 Hometown Hero.

(above) The Union County Trust Company in Elizabeth, NJ as it looked in 1915 when Juan was a clerk there.

(above) Bargos place was named in memory of Juan Bargos. It replaced 1st Avenue and may explain why many wrongly believed Juan was the first Cranford fatality. Alphabetically however Bargos lists first on the Cranford 86 roster.