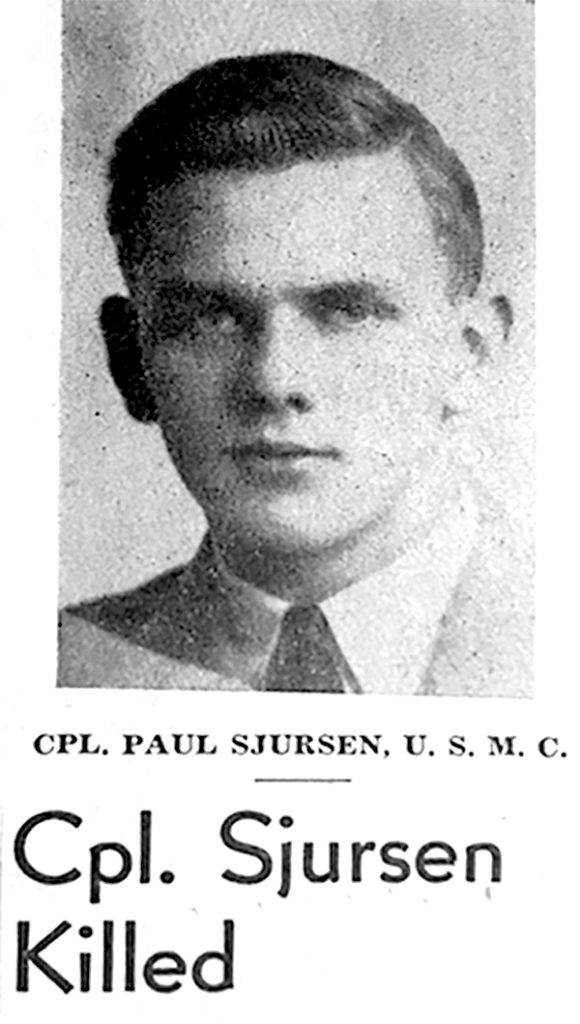

(above) Front page of the Cranford Chronicle in March 1944.

Meet U.S. Marine Corporal Paul W. Sjursen, one of Cranford’s 86 Hometown Heroes

By Don Sweeney with Lt. Col. Steven Glazer (Ret.), and Stu Rosenthal

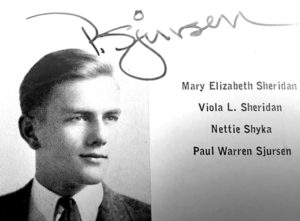

(above) Cranford High School’s 1940 yearbook, in 1940 asking someone to sign your yearbook was taken literally.

As we continue to research our elite group of 86 Cranford residents who heroically gave their lives in service to our country, we are reminded that some were involved in battles having less than memorable names or were simply identified by a hill number appearing on a map. And while these battles may not be recalled often or forever associated with a Pulitzer-winning photograph, the gallant men died for geography deemed essential by our nation for achieving overall victory. When a young man or woman joins the ranks of the military, they rarely have any say as to where they serve.

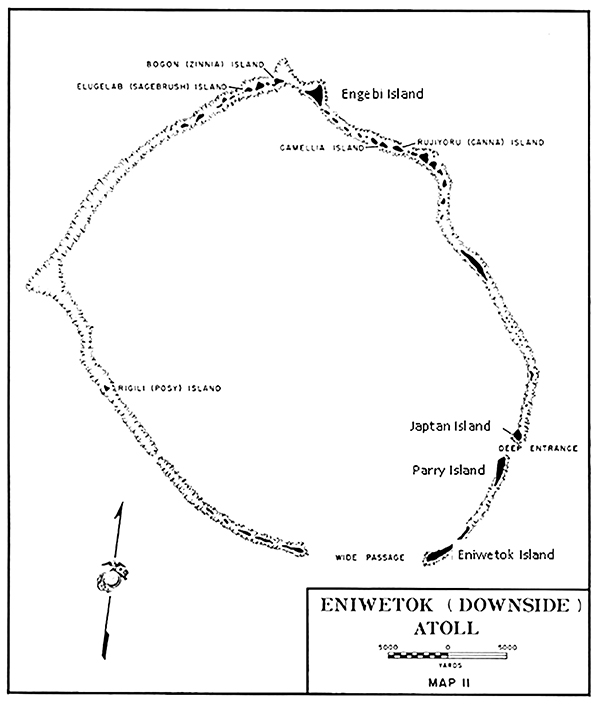

Generals and admirals, often far removed from the bloodstained trenches and roiled waves of battle, make grand decisions that will change the course of war – as well as the lives of the ranks who carry out their strategic plans. This month’s Hometown Hero, Corporal Paul Warren Sjursen (pronounced ‘Shoor-sen’), lost his life during one such battle in the Southwest Pacific during World War II. The Battle of Eniwetok (‘en-uh-wee-tok’) was part of an ‘island-hopping’ strategy adopted by President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill for the establishment of bases from which to launch Allied bombers in preparation for a final assault on Japan. Eniwetok Atoll, located in the northwestern part of the Marshall Islands, was a ring-shaped reef comprising some 30 small islands of coral and sand surrounding a lagoon. After capturing Eniwetok Atoll during World War I, the Japanese built airfields on its largest islands — Eniwetok, Engebi and Parry. Allied commanders deemed the capture of Eniwetok Atoll as a forward operating base with established airfields a major objective in 1944. As I started research on Corporal Sjursen’s story, I had never seen the word ‘Eniwetok’ and I had no idea what an atoll was. For 3500 American Marines and soldiers thrown into combat, Eniwetok Atoll would be a name most would never forget. For about 350, however, it would be the name on a final casualty list. Paul Sjursen was the third son of a Norwegian immigrant family. Born on the Fourth of July 1922 in Cranford, he lived first at 109 Severin Court, then briefly at 2 Clay Avenue before moving to 1 Oak Lane. And while Norwegian customs were taught to the four boys, Paul’s father Halvadan emphasized that only English was to be spoken in the home. Paul attended Lincoln School, where he was active in planning events like the Valentine’s Day Dance, a rather advanced job for a sixth grader we thought.

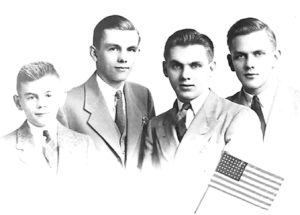

(above) The Sjursen brothers: Ralph 13, Herbert 24, Clifford 23 and Paul 19,

taken before the beginning of the US involvement in WW2.

At the Methodist Church, he was said to be prominent in youth activities. After graduation from Cranford High School in 1940, Paul found employment, as many did, at Western Electric in Kearny. It was the largest telecommunications manufacturing facility in the country employing 24,000. With the war raging in Asia and Europe, Paul chose to join the Marine Corps on January 24, 1942. He was the second in his family to serve; brother Clifford was already flying C-47 transport aircraft with the Army Air Corps. After three months of basic training and three more of infantry school in San Diego, Paul was ordered to American Samoa on July 19, 1942, for jungle training. One year later, in July 1943, Paul shipped out with his unit, the 22nd Marine Regiment, to Kahului on Maui in Hawaii, where he began training in amphibious landings and honing skills for an upcoming mission. In January 1944, he would depart Hawaii with his unit on the USS Heywood. The Battle of Eniwetok began with Engebi Island, at the northern tip of the atoll, measuring two miles long and one-quarter of a mile wide. It started on February 17, 1944, with a naval bombardment throughout the day and night to soften the objective. Patrick Castaldo, another member of our Cranford 86, was on board heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis providing fire support for his fellow Cranford High graduate. The following morning, Corporal Sjursen’s 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marine Regiment, began its amphibious assault on Engebi. Resistance was light and the forces moved rapidly inland. The objective was secured by late afternoon. Nevertheless, US losses included 85 dead and missing, plus 166 wounded. On February 19th, with intelligence reports of little resistance expected, a very light bombardment preceded the attack on Eniwetok Island — a larger, triangular island with each side measuring one mile. Here, the Japanese held strong “spider hole” positions within shallow camouflaged holes, some intricately connected underground to protect them from the naval bombardment. The Japanese defenders were thus ready for the landing of the Army’s 106th Infantry Regiment and the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 22nd Marine Regiment. Two days of fierce around-the-clock fighting finally brought victory.

(above) Marines of the 22nd Regiment approach the sandy shores of the Eniwetok Island, July 19th, 1944.

The ability of the enemy to defend their island was largely underestimated by US intelligence. American casualties were high. The final assault was for Parry Island, the smallest among the battle. Corporal Sjursen’s 2nd Battalion, with 5 days rest since the victory at Engebi, would lead the attack at the northern end of the island. The commanders were not going to make the same mistake made at Eniwetok. The big guns of the USS Tennessee and USS Pennsylvania, along with other ships, delivered an unprecedented 950 tons of explosives on the tiny island before the landing forces stepped foot on it. Additional firepower from artillery units with howitzer cannons on nearby Japtan Island added to the bombardment. It was the morning of February 22nd, a full day of intense fighting lie ahead against Japanese forces driven by a “fight to the death” dedication to their Emperor Hirohito. Our research team uncovered a blow-by-blow account of the day. (See the link at Cranford86.org) Our forces surged slowly forward on the narrow, 2-mile-long, tear-shaped island. Finally, in a nighttime, violent conclusion to the 6-day battle, the 22nd Marine Regiment had the remaining Japanese forces isolated on the southern end of the island called Slumber Point. In wartime Japanese style, the cornered defenders fought to the death. But the threat from any organized resistance was over. Eniwetok Atoll was effectively under US control. That evening, the Marine commander on Parry radioed a message to the fleet offshore, “We present you with Parry Island as a Washington’s Birthday present.” In response, the fleet’s flagship issued its own message, saying that our country’s flag was now moved 800 miles closer to Tokyo. Sadly, in the early morning of February 23, while “mopping up” enemy holdouts on the north side of Parry Island, our Hometown Hero Corporal Paul W. Sjursen, as the leader of a machine gun squad, was killed in action, making him one of the last Americans to die in the battle. He was only 22 years old. US casualties on Parry included 73 dead and missing, plus 261 wounded. Of the 3500 Marines and infantry involved in the entire operation, about 1 in 10 perished. The fanatical Japanese forces lost 3380. Only 105 surrendered. The Navy Seabees, a construction force, quickly turned battle-torn Eniwetok Atoll into an island headquarters.

(above) Parents Leonora (Arneson) and Halvdan Sjursen.– The brothers, from left to right are Herbert, Paul and Clifford.

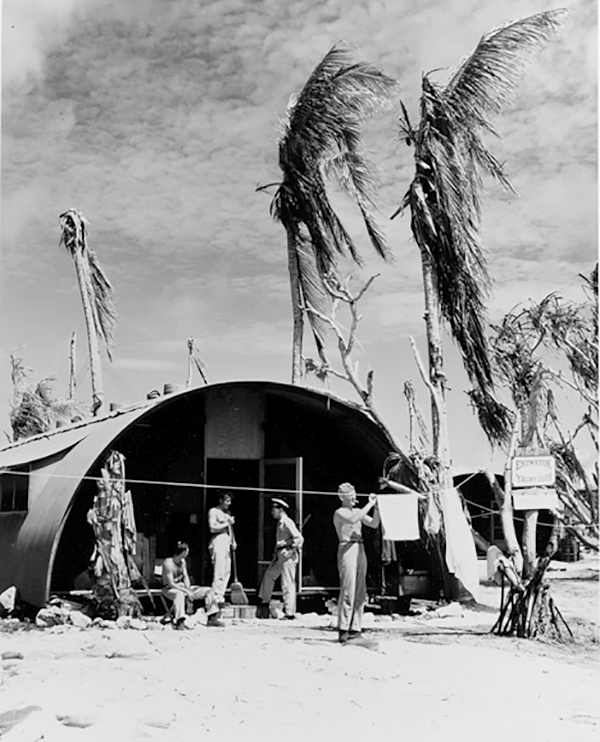

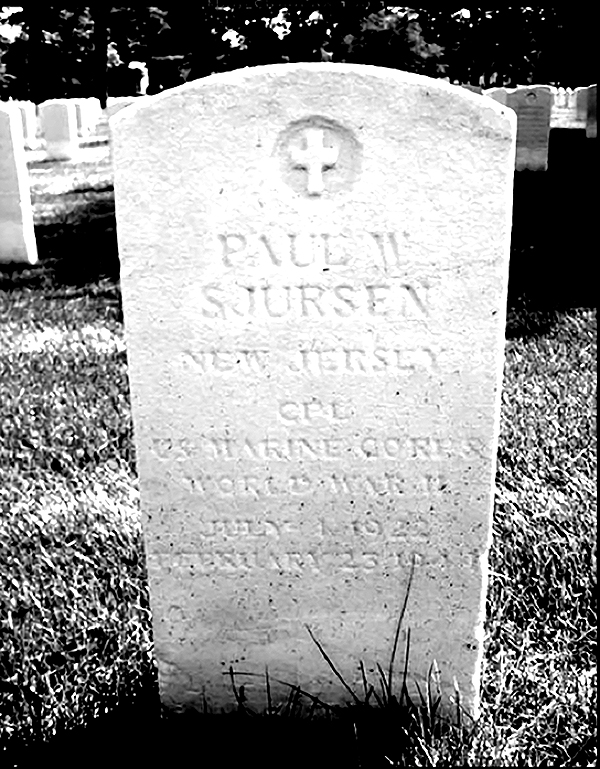

Construction started on Engebi Island within hours of the victory at Parry Island. With the latest military architecture making its debut in the early 1940’s, Quonset huts became hospitals, command centers and soldier housing. A 6,800 by 400 foot runway with dual taxiways was completed by March 11th. It was capable of handling the large B-29 Superfortress bombers that could not use aircraft carriers. The most advance aircraft repair and maintenance facility in the region was also created. The sacrifices made to take this coral ring proved vital to the war effort. The US now had dominance in the area with this forward base. Paul’s body was initially interred on Japtan Island in a temporary military cemetery provided for those who perished during the seizure of the atoll. Some accounts claim Paul died on Japtan. However, it was unoccupied by the Japanese at the time of the battle and was taken without a shot. Corporal Sjursen’s wartime memorial was held at the Cranford Methodist Church. Brother Clifford travelled across the country to be with his family for the service. Later, Paul’s remains were placed in a mausoleum in Hawaii near Schofield Barracks, and in 1947 the remains were moved to Beverly National Cemetery in Beverly, New Jersey (Burlington County). Paul had left behind at 1 Oak Lane his mom and dad, Leonora and Halvadan, and his three brothers: Herbert, who is now 101 years old and living in New Mexico; Ralph, who became a Methodist minister; and Clifford, who recently died at the age of 99. Clifford attained the rank of lieutenant colonel before retiring from the US Air Force Reserve. Our Cranford 86 committee attended his memorial service this July in Fanwood, in the hope of learning more about our honoree’s life. We had a chance to meet some of his family and experience Norwegian hospitality and customs that are still practiced today. Corporal Paul Warren Sjursen was a great American and one of our Cranford 86. For more links and pictures and maps go to Cranford86.org If you know anyone on our list of 86 and can help us find pictures and accounts of their lives, please contact me. We want to talk to you. If you’d like to have volume 1 of our first 12 Hometown Heroes, please call me, Don Sweeney (908) 272-0876. Visit Cranford86.org for all of the 15 stories we have told so far.

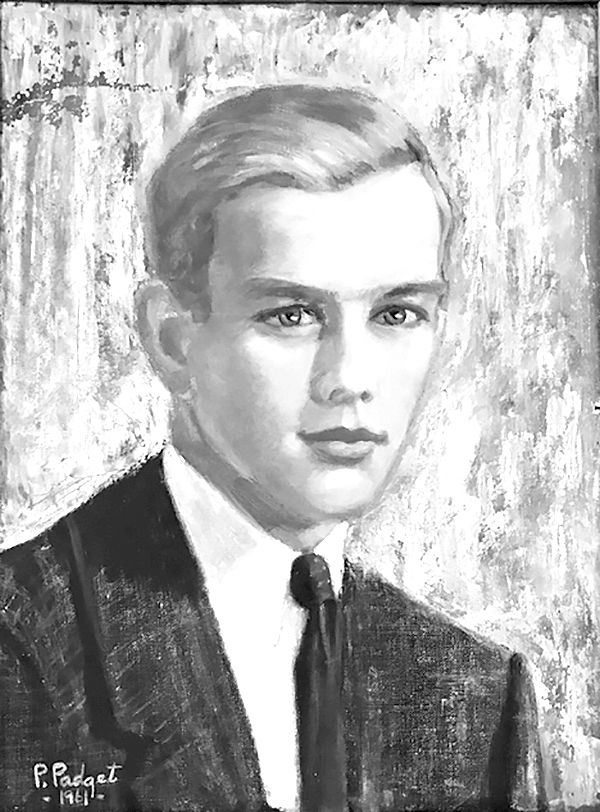

(above) A portrait painted in 1961 by an unknown artist gives us our first look at his Norwegian blonde hair and blue eyes, a handsome young man.

(above) A young Paul Sjursen, probably at their home on Severin Court.

(above) Quonset hut on Eniwetok Island, note sign “Eniwetok Yacht club”.

(aboove) The morning of February 23rd on Parry Island, when machine gun squad leader Corporal Paul Sjursen was killed in action. Note the machine gun and fixed bayonets as Marines “mop up” the area finding any hiding Japanese soldiers in the miles of trenches and tunnels. For all we know, this could have been Cpl. Sjursen’s unit.

(above) LVT Amphibious tanks (new US battle hardware) come ashore on Eniwetok.

(above) Paul W. Sjursen’s Gravestone at Beverly National Cemetery in NJ, near Philadelphia.