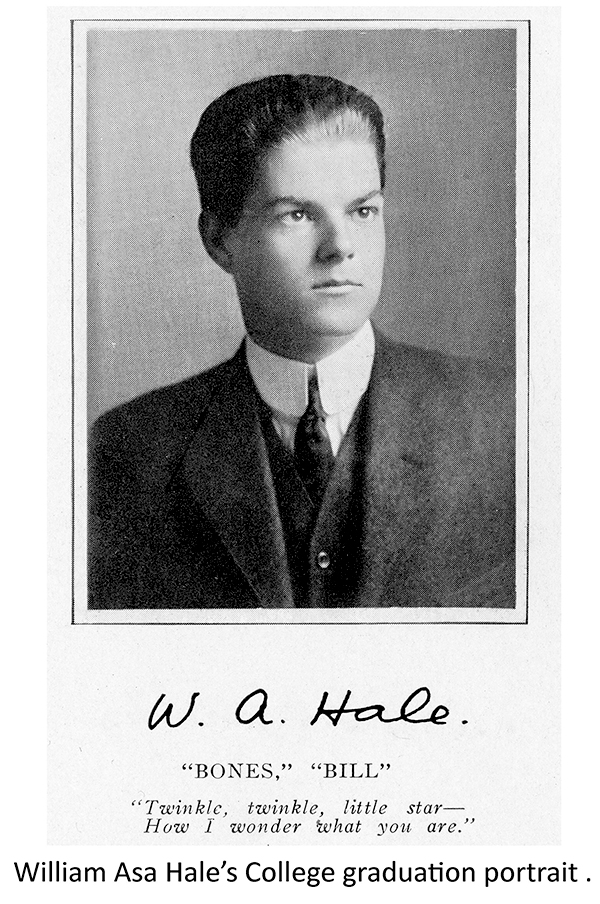

William Asa Hale’s College graduation portrait.

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of The U.S. entry to WW1: Meet William Asa Hale, Aviation Engineer for The U.S. Army, one of Cranford’s 86.

Written by Don Sweeney Research by Lt. Col. Steve Glazer (ret.), Cranford Historical Society

(above) A typical war plane from 1918, the period that W.A. Hale

was testing and flying aircraft at Curtiss Field in Buffalo, NY.

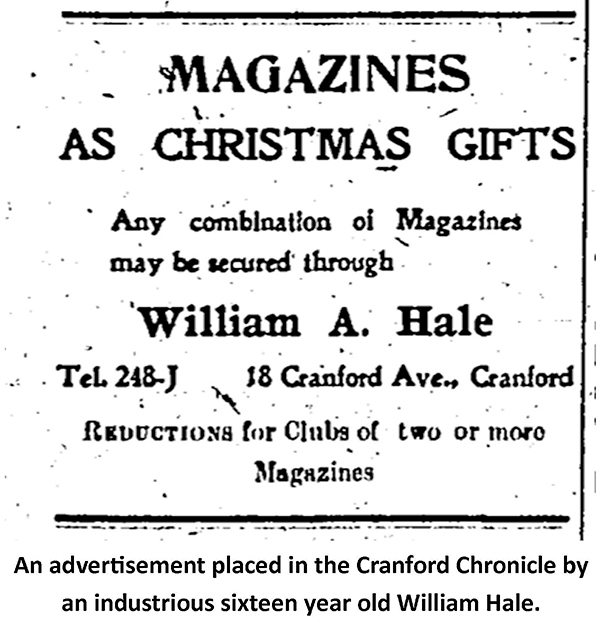

As I thumb through pages of new articles and other research we have accumulated in our search for stories of our Cranford 86, I struggle each month as to which direction to take. Which war, which hero? Such difficult decisions for me. As my wife and I walked the streets of Hoboken last Friday night, in route to visit our son at college, we passed a fence with posters advertising an event kicking off the two-year commemoration (2017-2018) of the 100th anniversary of our nation’s involvement in World War I. I thought that should be our direction for the rest of the year. I remembered one story about William Asa Hale, a young engineering graduate from Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken. His story personally touched me, particularly with my son Jimmy being a 4th year chemical engineering student at Stevens. I remember the empathy I felt for the parents of such a bright young man at the doorstep of a wonderful life. With my press deadline just one week ahead, I started my research process. My research partner Steve Glazer was my first call, followed by the Stevens library archive department, and finally use of my new Cranford Library website research skills. In just one day Steve delivered to my home over 25 amazing articles gathered from dozens of online sources. Stevens’s archives provided a crisp photo of the young graduate from their yearbook archives. I had all I needed to introduce William Asa Hale to the people of Cranford. I was excited to tell another amazing story of a fine young Cranford man. Born in Brooklyn in 1894 to Mr. and Mrs. Edward Hale, they moved to Cranford before William started school. As a popular member of the student body at Cleveland High School, Cranford’s public high school, now Cleveland Plaza, William played varsity baseball and graduated with the class of 1912. Early evidence of William’s industrious character was found in a Cranford Chronicle advertisement he placed for the sale of magazine subscriptions for Christmas gifts in 1910 as an ambitious sixteen year-old. He later entered Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ, and graduated in 1916 with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering. Interestingly, civil and mechanical engineering were the only two options at Stevens in 1912. While there, he was an accomplished member of their varsity track team. A historical search shows William’s lineage dates back to Asa Hale (1759-1843), a soldier in George Washington’s military forces who served under General Lafayette during the Revolutionary War in 1777 in the defense of Lake Champlain. This military ancestry also explains William’s middle name. Being just twelve years after the Wright brothers took flight at Kitty Hawk, William was fascinated by aviation. It is told that he was a born mechanic. He had a thorough familiarity with the construction of motors, explaining his direction in education after high school into mechanical engineering.

Army Cadet Homer V. Sharp

His first job out of college was with the Standard Aircraft Company at their Elizabeth plant. After just two months he was promoted to the position of consulting engineer in the production of aviation propellers. He was soon regarded as one of the nation’s foremost propeller experts. One of William’s employers is quoted as saying that “he has the brain of a 40-year-old engineer.” An article from The Statesman Journal of Salem, Oregon, also spoke of William’s visit to a textile plant there. The town was thrilled that “W. A. Hale” was considering their company to manufacture flax material to be used in the construction of wings on bi-planes. With America’s entry into World War I in April of 1917, the idea of aircrafts being added to the nation’s arsenal became a production priority. William’s talents were quickly focused by his new employer on the design and testing of planes destined for the battlefield in France. From Elizabeth, he was transferred to the government’s flying field in Dayton, Ohio. There, William, as a civilian engineer in the aviation section of the signal corps, was employed in support of the war effort on aircraft for the U. S. Army Air Corps. In short order, he was sent to Curtiss Field in Buffalo, New York. This was the nation’s hot spot of military aircraft testing. During a seven-week period of testing at this time, six test pilots were killed in flight. During a test flight of the largest flying machine of its day, on July 15, 1918, William was aboard as an inspector observing a new propeller design. The plane was being piloted by Homer Sharp, an Army aviation cadet from Fort Worth, Texas. Before the flight, William was told by his commanding officer that he didn’t have to make this flight, that another inspector could do it. William was reported to have replied, “It’s my duty.” He said the he wouldn’t feel that the test was sufficient or complete unless he went himself. William was also noted for this comment: “A fact that is often lost sight of is that when our planes are delivered over there, they must be right. It’s my job to make sure they are right.” During the flight it is believed that the aircraft’s engine failed at a very low altitude, after which the plane went into a tailspin and crashed. The motor crushed both young men aboard. William was killed almost instantly and Homer Sharp, the pilot, was critically injured, dying later that day. It was reported that virtually every bone in both their bodies, including their heads, were broken. A bloodstained, chilling letter found in William’s pocket told of a premonition of his death that day. In a letter later published in the Cranford Chronicle as a “tribute from a chum,” it was written about William: “While engaged in his work he developed and standardized a great deal of data on propellers. His ability and energy resulted in his assignment to propeller testing with a roving commission which took him to large industrial plants and flying fields all over the country. His advancement was rapid and he was recently rated as consulting engineer on propellers. War has stolen a fine engineer from our country and a dear friend from us all.  Although not a flier, his testing and observation work necessitated frequent flights with a pilot, and it was in one of these that he met his ultimate death. His life was given to the service of his country, the same as a soldier in the front.” A poignant letter submitted to the Cranford Chronicle by William himself, the week after he, a civilian, was listed in the paper along with all uniformed service members on the town’s Roll of Honor, read as follows. “Words mean nothing and only actions count, but I must demand that in fairness of those who have a right to such recognition, you remove my name from the town honor roll, which you published May 17, 1917. Let no one confuse my work, which is and will be like that in any other business office, with the danger and hardships endured by those actively engaged in flying service. That I am engaged in designing airplanes for the use of the U.S. government is fortunate and interesting but it entitles me to no more honor than does the occupation of any other man who, sacrificing nothing, pursues the usual routine of his business.” These self-deprecating words were written 14 months before William indeed sacrificed all. The township of Cranford disagreed with the degree of dedication William Asa Hale gave to his country. His name was not only enshrined on our town’s World War I tablet at Memorial Park, but also became one of the street names commemorating our World War I heroes, with “Hale St.” being emblazoned on the distinctive cement-and-ceramic tile street signs that were erected after the war and still stand today. William’s funeral was held at 18 Cranford Avenue where he was raised and molded into the selfless man he became. He was buried at Fairview Cemetery in Westfield with military honors, a rare event for a “civilian.” It is unbelievable to me that this story that I share with you today was about a man who died when only 23 years old. William Asa Hale was a great American and one of our Cranford 86. If you have any information about one of our Cranford 86 please reach out to me. I am anxiously seeking additional information about this special group of men. Email me at djsween@aol.com or call (908) 272-0876.

Although not a flier, his testing and observation work necessitated frequent flights with a pilot, and it was in one of these that he met his ultimate death. His life was given to the service of his country, the same as a soldier in the front.” A poignant letter submitted to the Cranford Chronicle by William himself, the week after he, a civilian, was listed in the paper along with all uniformed service members on the town’s Roll of Honor, read as follows. “Words mean nothing and only actions count, but I must demand that in fairness of those who have a right to such recognition, you remove my name from the town honor roll, which you published May 17, 1917. Let no one confuse my work, which is and will be like that in any other business office, with the danger and hardships endured by those actively engaged in flying service. That I am engaged in designing airplanes for the use of the U.S. government is fortunate and interesting but it entitles me to no more honor than does the occupation of any other man who, sacrificing nothing, pursues the usual routine of his business.” These self-deprecating words were written 14 months before William indeed sacrificed all. The township of Cranford disagreed with the degree of dedication William Asa Hale gave to his country. His name was not only enshrined on our town’s World War I tablet at Memorial Park, but also became one of the street names commemorating our World War I heroes, with “Hale St.” being emblazoned on the distinctive cement-and-ceramic tile street signs that were erected after the war and still stand today. William’s funeral was held at 18 Cranford Avenue where he was raised and molded into the selfless man he became. He was buried at Fairview Cemetery in Westfield with military honors, a rare event for a “civilian.” It is unbelievable to me that this story that I share with you today was about a man who died when only 23 years old. William Asa Hale was a great American and one of our Cranford 86. If you have any information about one of our Cranford 86 please reach out to me. I am anxiously seeking additional information about this special group of men. Email me at djsween@aol.com or call (908) 272-0876.