(above) 2nd Lieutenant Alan M. Okell posing with his flight wings proudly displayed.

Meet 1st Lieutenant Alan M. Okell World War 2 Flight instructor, One of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney with Stu Rosenthal, Steve Glazer and Jim D’Arcy

(above) Mr. and Mrs. Alan M. Okell on their wedding day.

In 1942, the newly married Alan M. Okell of Cranford was assigned to MacDill Air Field in Tampa, Florida as a young instructor pilot in the U.S. Army Air Corps, ready to teach novice pilots how to fly a new advanced aircraft, the Martin B-26 Marauder. It was faster than any bomber preceding it, with a small wingspan and advanced defensive guns on board. And while B-26 squadrons would eventually help score victories at Normandy and throughout Europe, the bomber earned the regrettable nickname “widow maker” among the instructor pilots and students. The nickname proved much too prophetic for him. The story to follow will help explain why and introduce our next Cranford 86 American and hometown hero.

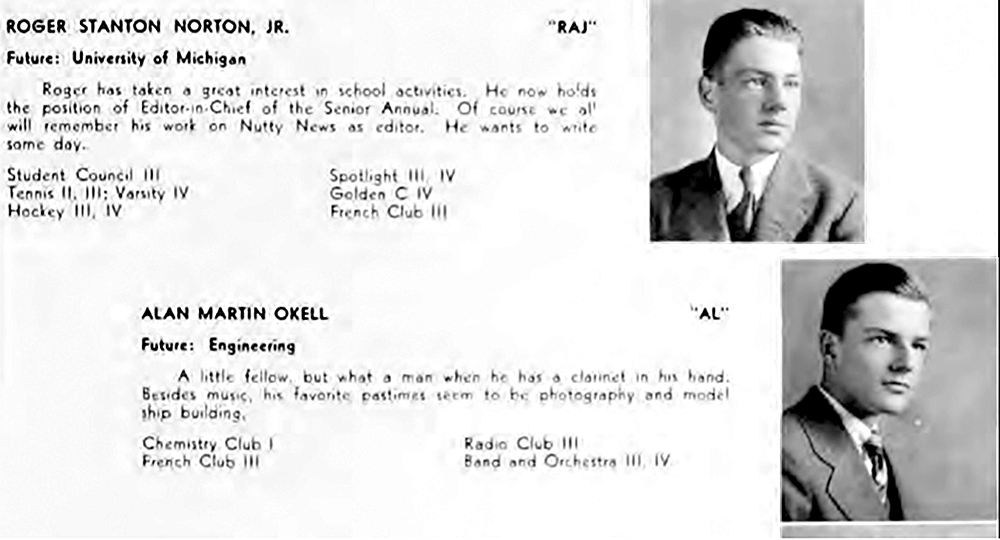

Alan Martin Okell was born on October 24, 1919 in Orange, NJ and moved to 6 Willow St. in Cranford at the age of seven. He attended Grant and Roosevelt Schools, skipping second grade and graduated from Cranford High School in 1936 while still only sixteen. Alan was a classmate of Roger Norton, another of Cranford’s 86. Following a year of additional studies, Alan entered the School of Engineering at Rutgers University and its ROTC program.

During his school years, Alan developed a keen interest in photography and music. He played clarinet in the high school band and orchestra, joined the ROTC band at Rutgers, and was a member of the choir and glee club. With a passion for sailing, Alan was a member of Breton Woods Yacht Club in Brick where he took first place at their sailboat event in 1940. During his third year at Rutgers, Alan left for unknown reasons and took a position at International Harvester Company. Alan then joined the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet on November 1, 1941, just a month before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II.

The next series of months, following the destruction of much of our air and naval capabilities at Pearl Harbor, was a rush to build up our ability to wage war. From a country with a small fleet of 1,700 aircraft in 1938, we grew to an amazing 324,750 warplanes by 1946. In addition, 110,000 aircraft mechanics and 193,000 pilots were quickly trained. While these numbers of mass production have been looked at by the world in awe for years, the haste in which such mass production took place caused the loss of many young brave lives. Sadly, the life of our Alan M. Okell may have been one of them.

One of the weaknesses of the nation’s air fleet at the start of the war was the lack of a high-speed dual-engine, medium-sized bomber with the capability of carrying a bomb load of 4000 lbs., the same load as Boeing’s four-engine B-17 “Flying Fortress” bomber. A challenge was put out to the aircraft industry, with many companies submitting proposals. The Glen L. Martin Aircraft Company responded with their bid for the B-26 Marauder. The Army made an unprecedented decision accepting the Martin proposal, ordering 201 bombers without a prototype ever being built.

(above) The front view of the B-26, note the bombardier under the cockpit with full view of the terrain below.

With its innovative design consisting of a bullet-shaped fuselage, rounded glass nose with dual machine guns and a dorsal turret, the Marauder was just about the hottest thing flying at the time. However, with its short wingspan, 2 huge 2000-horsepower engines and a faster takeoff/landing speed of about 140 miles per hour, accidents were happening at alarming rates in the hands of traditional pilots unaccustomed to the sheer power and progressive speed of the formidable B-26. Seventy-five percent of all training was taking place at MacDill Air Field, now MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. During one 30-day period, 15 training crashes happened above Tampa Bay with an average of five men on board. “One a day in Tampa Bay,” legendary among the airmen, was the perceived accident rate for B-26 bombardment units training at MacDill during this period, earning the plane the nickname “Widowmaker.”

Alan received his commission and officer’s wings on the Fourth of July, 1942. After graduating from advanced aviation training at Brooks Field in San Antonio, Texas, Lt. Okell was assigned to the 314th Bomb Squadron of the 21st Bomb Group, 3rd Air Force, at MacDill Air Field, to train young aviators on the new Martin B-26 Marauder. On March 13, th 1943, during a training flight he was piloting, Alan’s B-26 went out of control and crashed into two feet of water in Tampa Bay. All five crewmen died. It was just three weeks after Alan had received his promotion to first lieutenant. Ironically, nearly a half century later, our new researcher, Stu Rosenthal, was an Air Force cadet that frequented MacDill Air Force Base in the early 1990’s, when F-16 fighter pilots were being trained over the same waters in which Alan and his aircrew perished.

As the B-26 crashes mounted in Tampa Bay, a congressional hearing was called. The head of Glen L. Martin Company, Glen Martin himself, was called to testify. He faced Senator (later President) Harry S. Truman. Truman demanded to know why the wings couldn’t be redesigned to make the plane more stable and easier to fly. Martin claimed that there was nothing wrong with the aircraft if operated by experienced pilots. He made a statement that they already had the contract so they didn’t have to make any changes. Senator Truman, in classic form, leaned forward and said the contract could be cancelled just as well. Martin went back to his plant in Baltimore and made the necessary improvements.

(above) The Martin B-26 Marauder in flight. Note the Glass nose for the enhanced view of the bombardier and the dorsal location of the machine gun turret for rear protection.

In all, 5228 B-26 Marauders were manufactured throughout the war. B-26 Marauders were among the first wave of Allied aircraft to attack the beachheads of Normandy on D-Day, attacking German coastal gun batteries. B-26 aircrews saw action throughout Europe including Caen, St Lo, Falaise Gap, Brest and the Bulge. In the end, it was perceived as a successful warplane. Its smaller profile and advanced speed made it very hard to be taken down by anti-aircraft guns, and it could operate on airfields with shorter runways. By the end of the war, it had the lowest combat-loss ratio of any plane in Europe. Only eight remain today. One, “Flak-Bait,” currently hangs intact in the collection of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. It flew 207 operational missions in Europe, more than any other American aircraft.

On July 19, 1942, 15 days after receiving his commission as a second lieutenant, Alan had married Peggy Haagenson of 7 Orange Ave. in Cranford. Their son, Alan Robert Okell, never met his father. At the time of her husband’s death, Peggy was 3-months pregnant. We spoke to Alan from his Florida home. He just lost his mother last January. Alan said that although he never met his dad, many said he was a great guy. Alan was thrilled that we were honoring him. He hopes to visit with us in Cranford next Memorial Day to see his father’s banner dedicated at Memorial Park.

After the crash in Florida, Lieutenant Okell’s remains were returned to Cranford for funeral services. The promising pilot was buried at Fairview Cemetery. I visited Fairview and was unable to locate his final resting place. After much searching with the help of staff members at the cemetery, we finally found his partially hidden gravesite next to his parents, Stanley and Beatrice Okell. The bronze memorial plaque provided by a grateful nation was overgrown and there was no American flag placed over it, as was the case for other veterans. Before I left the hero’s grave, I cleaned the plaque and raised a new American flag over it. It was the least I could do at the time.

First Lieutenant Alan Martin Okell was a great American and one of our Cranford 86.

We are now in our second year as we move towards our goal of telling the stories and unveiling the faces of the 86 men behind the bronze plaques at Memorial Park. If you want to receive the 36-page full-color commemorative booklet containing the stories told so far, or if you are interested in sponsoring one of the upcoming hero’s banners, please contact me at djsween@aol.com or 908-908-447-6511.

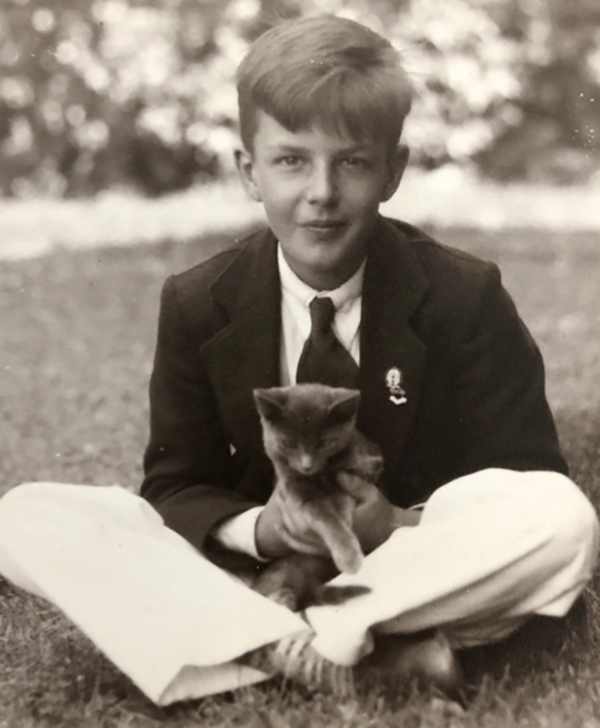

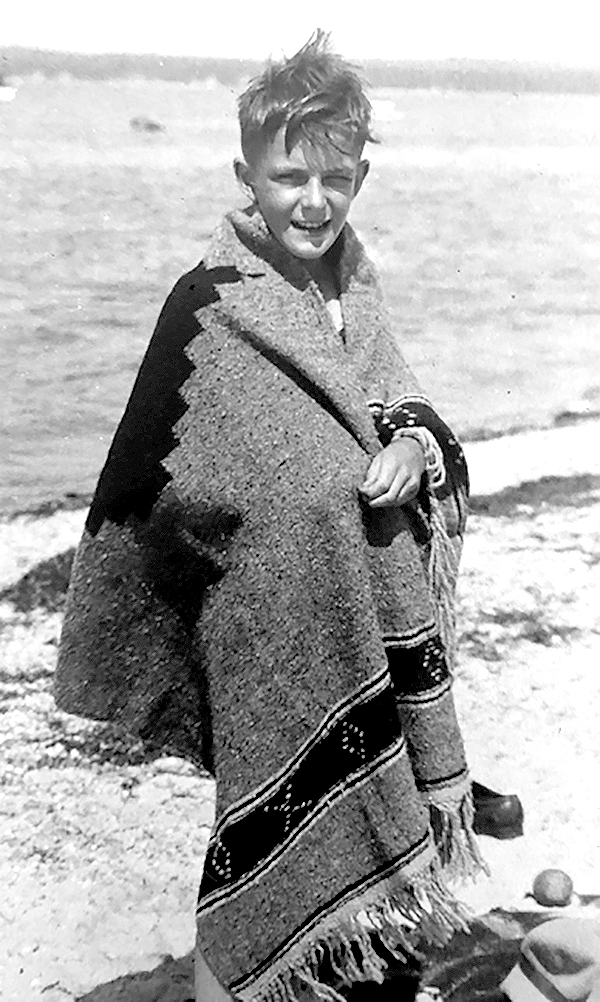

(above) Young Alan Okell

(above) Young Alan Okell at The Jersey shore.

(above) The Okell Family at home in Cranford, his mom Beatrice, Father Stanley, his sisters Jean and Kathleen His grandmother and Alan’s wife Peggy who just passed away this January 3rd, at the age of 96.

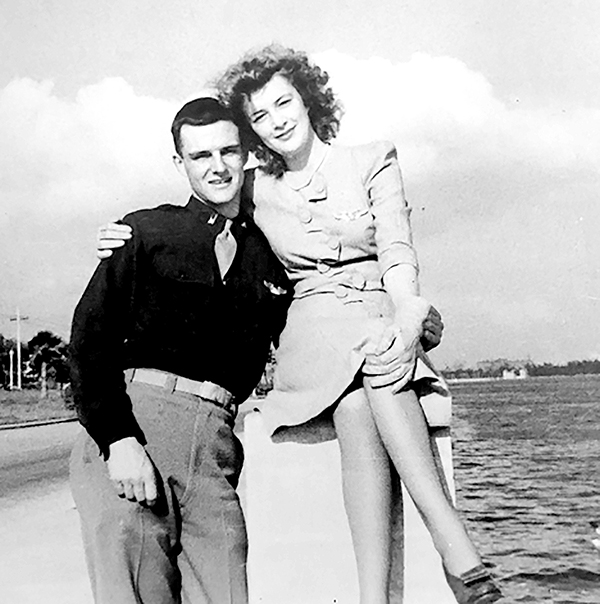

(above) Alan and Peggy by Tampa Bay. Sadly it was in Tampa Bay that his B-26 bomber would crash and take his life, shortly after this picture was taken. Note Peggy wearing his wings

Alan Okell as a member of the 314th Bomber squadron would have worn this arm patch, interestingly designed by Walt Disney himself.

(above) Alan Okell and then fiancé Peggy Haagenson of 7 Orange Ave. in happy times.

Alan Okell Place dedicated to the memory of an American and hometown hero.

(above) The 1936 Cranford yearbook Roger Norton and Alan Okell were classmates and both became casualties of World War 2. Sadly in a four year period, 57 Cranford men lost their lives in service to their country.