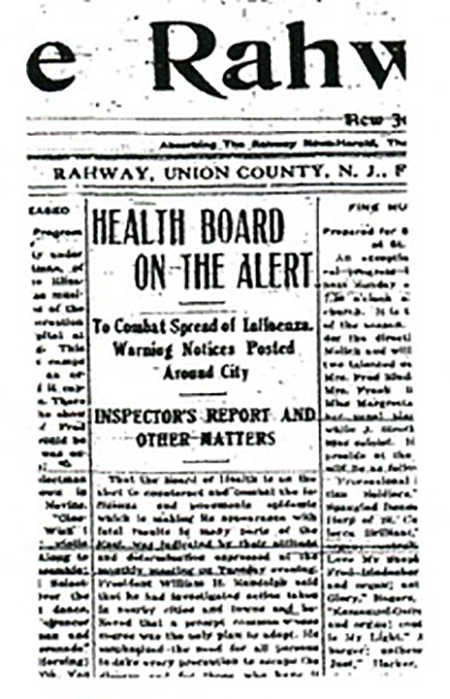

(above) Headline from the Rahway Record, October 4, 1918.

Rahway History Article – 1918 Epidemic

Submitted by Al Shipley, City Historian and Rahway Library Research Consultant

One-hundred and two years ago, the world was plagued by an influenza epidemic that would affect one-fifth of the world’s population and one-fourth of the population of the United States. By the time it had subsided, the virus, known as the Spanish flu, claimed the lives of an estimated fifty million people. In cities like Rahway, situated on the densely populated east coast, the epidemic had a deadly effect and afflicted thousands of residents. Surprisingly, the measures taken by the local authorities and the ways in which the citizens responded to combat the silent killer were very similar to the actions taken and displayed during the current crisis.

The first phase of the epidemic surfaced in the late spring and proved to be relatively mild. Called “the three day fever,” victims recovered after only a few days of illness and the death count was relatively low. When the disease struck again in the fall, however, the results were far more devastating. In late September the effects of the epidemic were being felt throughout Union County and by October 1st, Rahway’s Board of Health announced regulations to halt the spread. Broadsides were posted in neighborhoods around the city with the following notice: “To prevent the spread of Spanish influenza, sneeze, cough, or expectorate (if you must) in your handkerchief. You are in no danger if everyone heeds this warning.”

In a lengthy front page newspaper article the board outlined ten guidelines to help one escape the disease and prevent its spread:

- Don’t jam entrances to railways, theaters, and places of assembly.

- Don’t put unclean things into your mouth or eat in dirty places.

- Don’t expose yourself to cold or wet.

- Don’t go out if feeling unwell.

- Don’t forget to use handkerchief covering mouth when coughing or sneezing.

- Don’t eat without first washing hands.

- Keep the home as well as the office and workroom well ventilated.

- Avoid overeating.

- Exercise in the open air.

- Stay at home.

Even with these guidelines in place, by the end of the first week, 2,000 cases and eleven deaths were reported.

Fortunately, from the onset, there was complete cooperation between local physicians, hospital, health, and city officials. A ban was quickly placed on all kinds of public gatherings. Schools, churches, theaters, dance halls, pool rooms, lodge rooms, and other places where numbers of people might congregate were closed. School dances, football games, Columbus Day celebrations, parades, and social events of churches and fraternal organizations were all cancelled. Public funerals for all who died from the flu were forbidden. Pharmacies, saloons and ice cream stores were allowed to remain open, but in the case of the latter two, only to sell products in packages to be taken out. The general rule in those venues was “Buy it and beat it!” The police were ordered to break up any gatherings and move people along. By the next morning streets were practically deserted.

Those who contracted flu symptoms were directed to go promptly to bed, in a separate room if possible. Family members and visitors were instructed to stay out of the room and not use any dishes, glasses, or utensils used by the sick person. In all cases it was required that a physician be notified to determine if the patient required hospital care.

Rahway’s small, twelve-bed hospital, adequate during normal times, was quickly overrun with cases. To fill the void, arrangements were made with St. Mary’s Church to use their hall as a make-shift hospital annex. Koenig’s Hall, a large space on Main Street, was also converted to handle the increasing numbers. Fifty beds were brought in from the army hospital in Colonia to be used in the two halls. Members of the Elks lodge on Milton Avenue and the owner of the Empire Theater on Irving Street also made their halls available, although they were never used.

Average citizens rose to the occasion to respond and assist in any variety of ways. A call went out to all women with any type of nursing experience to help doctors and trained nurses with the countless duties needed in the annexes. Chemists from Merck who had pharmaceutical experience assisted in preparing prescriptions and dispensing drugs at local drug stores filling in for store employees who were sick with the virus. Young teens took on harvesting jobs at an east Rahway seed farm so the regular workers could help at the St. Mary’s annex. The Women’s Auxiliary of the Rahway Hospital organized food drives to supply the hospital and annexes. Citizens responded in a generous manner donating canned milk, bread, potatoes, cereals, fresh fruits and vegetables, and homemade delicacies.

By mid-October, the crest of the epidemic had passed and the number of new cases was decreasing daily. On Thursday, October 24, officials deemed it was safe enough to reopen businesses. Schools would be reopened on Monday, November 4. Most churches waited until Sunday, November 3rd before holding services. Although the ban had been lifted, the daily routine of life was not fully normalized. A portion of the public was cautious about resuming their usual daily activities, and remained wary of large gatherings. The number of cases continued to decline, but the specter of the virus lingered. As the weeks went on, practically every patient who developed pneumonia did not survive which added to the fatality rate.

An editorial in the Rahway Record praised the health authorities and noted that it was their early and dramatic measures and the cooperation of the citizens that saved the city from reaching the dire numbers that had been predicted when the epidemic hit. Still, the numbers were terribly high. It was estimated that almost 4,000 residents in a city of 12,000 were affected and that close to 100 persons died, making the epidemic the deadliest in the history of the city.

(above) Rahway’s original hospital, located on the corner of Jaques and W. Hazelwood Avenues, as it looked at the time of the epidemic. The building served as a hospital until 1929 when the present hospital was built on Jefferson Avenue. The old building was converted into a multi-unit dwelling and still stands.