Unknown Woman Murder of 1887

Submitted by Al Shipley, City Historian and Rahway Library Research Consultant

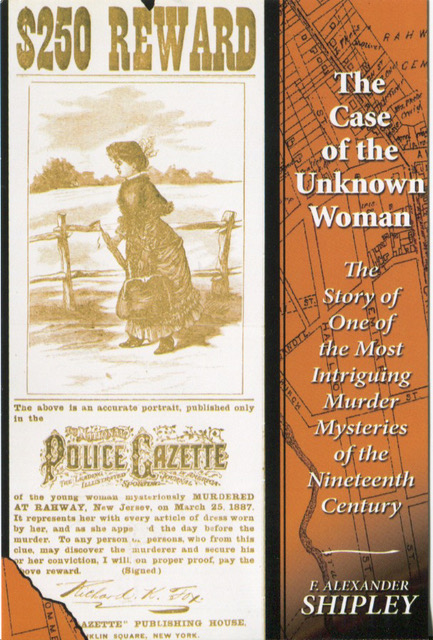

It’s hard to imagine that news of a strange crime which took place in Rahway 135 years ago could captivate attention and excite interest all across the United States and even reach countries on the other side of the Atlantic. But the brutal murder of a young woman and the ensuing layers of mystery that unfolded during the investigation, created one of the most intriguing murder mysteries of the nineteenth century.

On the morning of March 26, 1887, Alfred, Thomas, and Irving Worth set out along Jefferson Avenue for their two mile walk to work. As they reached Central Avenue, they spied something on the ground that appeared to be a discarded coat. The brothers approached the object for a closer examination and were horrified to discover a bloody corpse of a young woman.

Rahway Police Chief William Tooker was immediately summoned, but by the time he arrived at the scene, over 100 curious neighbors had beat him to the site. Many were hovering around the body and others were kicking through the scrub grass searching for clues. Tooker restored order as best he could and finally had the opportunity to examine the awful scene.

The ground around the body showed every sign of a terrific struggle. The woman had been brutally murdered. Her throat had been slashed from ear to ear and her face was discolored with bruises. She was blue eyed, brown haired, and appeared to be in her early to mid-twenties. She was dressed in a dark green dress, wore tan kid gloves and was clad in a pair of shoes which looked foreign made. Near her body lay a fur cape, a black straw hat, and a parasol. A small willow basket and nine eggs, all but three of which were broken, were strewn among the other effects.

While Tooker was making his survey, two men came up to him with objects they had uncovered. One handed him a small black bag which he said he found in the river by the Jefferson Avenue Bridge. The other man gave the chief an item of even greater interest. It was a bloody knife. These items; the clothes, the eggs and basket, the black bag and the bloody knife would make up the primary bits of evidence as the search would begin for the killer.

There was, however, an unusual and unsettling development. Of all those who viewed the corpse during the course of the morning, no one recognized the woman. It was this unusual twist that would take the crime out of the realm of a local story and make it one that would pique the interest of a nation–wide audience.

By noon on the morning of the murder, beat reporters from the Elizabeth, Newark, and New York City papers had arrived and by the next day reporters from as far off as Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. were in town to try to break the story. Professional and amateur detectives hurried to the community. Rewards were offered by the state of New Jersey, the local city council, wealthy citizens, and crime magazines. Photos of the woman would soon be circulated throughout the major cities on the east coast and as far west as San Francisco. Readers in Salt Lake City, Fort Worth, Chicago, and Atlanta followed the story in their local dailies.

Public viewings were held in Ryno’s Funeral Home on the three Sundays after the body was found with the hope someone would identify the victim. Although a total of over 10,000 visitors would come to Rahway on those Sundays and stand on long lines to get a glimpse of the woman, no one could offer a positive identification.

The Rahway religious community, upset by the lack of dignity and decorum during the public viewings, urged the authorities to give the woman a proper funeral service and burial. The powers-to-be did allow a funeral service to take place on April 11, but would not give permission to bury the body. There was still a chance someone would recognize the victim.

Early on, a jury had been selected with the assumption that an inquest would be scheduled and witnesses called. On Monday, April 18, the first of a series of six sessions began. Twenty–five citizens testified, but nothing conclusive ever came out of the inquest. As many as fifteen men were pursued as suspected killers. The ones apprehended were questioned and a few spent a night or two in jail. But in the end, no one was ever convicted.

On Tuesday, May 3rd, thirty–eight days after the body was found, the unknown woman was finally buried in a rear section of the Rahway Cemetery. Six New York reporters served as pall bearers. Of the three-dozen people who attended the burial, two women swore they knew the name of the victim. The only problem–each argued it was a different person.

In the months that followed more leads concerning the killer would come forward. One story surfaced which named the owner the basket, and in June, a man in Salem, Illinois confessed to the crime. Both stories, however, led to dead ends. Ownership of the basket was never proven, and when the confession of the Illinois man was checked out, it was surmised he was a “crank” looking for free passage back to the east coast.

Although the names of some 51 women, thought to be the victim, had been brought to the authorities since the beginning of the investigation, no positive identification was made. In the next fifteen years, identifications continued to come forth, but with the body interred and the passage of time, it was becoming next to impossible to give the woman a rightful name.

Who was the woman? Who killed her? What was the motive? No one to this day has been able to solve the uncanny mystery.