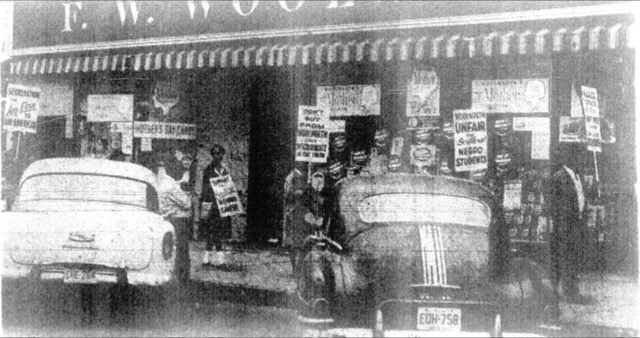

(above) Pickets walk in front of the F.W. Woolworth store at 1433 Main Street Rahway, NJ, in protest against the segregation policy practiced by chain store lunch counters in the south.

Rahway High Grad at the 1961 Civil Rights Sit-In

Submitted by Al Shipley, City Historian and Rahway Library Research Consultant

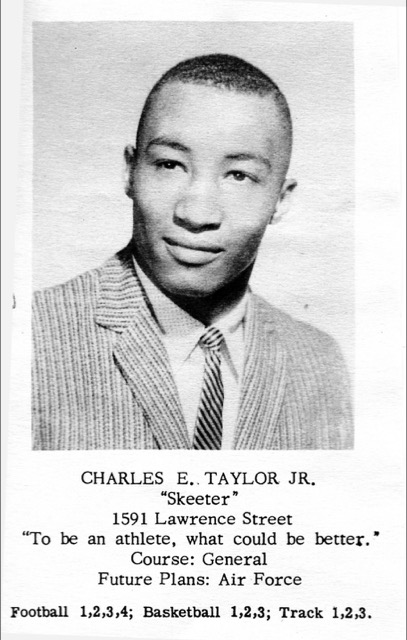

(above) Rahway High School year book photo (1958), Charles E. Taylor Jr. “Skeeter”

Sixty years ago, in February 1960, a pivotal event occurred that would become a catalyst in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, when four black students were denied service at a lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. The incident sparked protests throughout the south and within a few short months, northern cities, including Rahway, were staging protests of their own. The country-wide protests would continue and on January 31, 1961, Charles E. Taylor, a Rahway High School graduate, class of 1958, along with a group of fellow college students, would participate in a sit-in that would have a lasting impact on the strategy of civil rights activists.

The vile practice of segregation was the law of the land throughout the south and had been an accepted part of the culture for decades. Several sit-ins had taken place in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, but it was the one on February 1, 1960, that fueled a movement. At 4:30 on that February afternoon, four young black men, all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, took seats at a “whites only” lunch counter at the local Woolworth’s 5 & 10. After their order was refused, the four remained at the counter until the store closed. They returned each day for the next six days, each time bringing more protesters. By the sixth day, over 1,000 protesters from around the state packed themselves into the store. Soon, students from other parts of North Carolina staged their own sit-ins in any store that followed segregation practices.

The protests became national news as newspaper and television coverage began changing public opinion by shedding light on the cultural inequalities that were a way of life in the south. As a result, cities throughout the country began staging protests at nationally owned chain stores who allowed segregation in their southern businesses. In Rahway, marchers picketed in front of the Woolworth store on Main Street to put pressure on the Woolworth brand. The marchers carried placards that read, “Segregation in any form is Un-American.”, “Support the Southern Negro Cause.”, and “The NAACP Supports Southern Students against Jim Crow Lunch Counter.”

Changing culture, however, is not easy and takes time. Although the Woolworth Company actually did begin to abandon their segregation policies (nation-wide, their sales had dropped over one-third), many chain stores in the south held fast to their “whites only” rules. It was not until 1965 that federal laws were finally enacted to end segregation.

Of the protests that would take place after the Greensboro sit-ins, the one which occurred on January 31, 1961, involving Charles Taylor, the Rahway grad, gave activists a new weapon to use in the fight for equal rights. Taylor had been on his Christmas break from Friendship Junior College in Rock Hill, South Carolina and upon returning to the campus was asked to join a group of students who were headed downtown for a protest. Ten students entered a McCrory’s 5 & 10 and took seats at the counter. The store manager asked them to leave and when they refused, they were arrested and sentenced to thirty days in jail. All ten students refused to accept bail and were sent to a prison farm where they experienced the harsh brutalities of the southern penal system. Taylor, the only northerner in the group, spent five days on a chain gang encountering for the first time the unjust legal system of segregation and hatred. Fearing his scholarship would be forfeited, he received money from home, paid his bail and was released. The other nine remained in jail.

The event had historical significance in that the concept of “jail, no bail” relieved the civil rights groups from the financial burden of posting bail for the release of activists and reversed the burden to the white authorities who had to take on the expense for jail space and food. This ploy became a strategy that was used throughout the civil rights movement.

In 2007, a historic marker outlining the story of the ten students was placed in front of the establishment that housed the McCrory’s back in 1961. Inside the building, which was still a restaurant, the names of all ten students, including Charles Taylor, were inscribed on the backs of the counter chairs. Justice was further served in 2015 when a South Carolina judge (who happened to be the nephew of the judge who sentenced the ten in 1961) overturned the convictions stating, “We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history.”