Meet Torpedoman’s Mate 3rd Class Emil F. Frank, One of Cranford’s 86

Written by Don Sweeney and Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault, Research by Don Sweeney, Barry Mazza and Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault. Military fact checking by Vic Bary

As the founder of the Cranford 86 project, I am often approached by residents who express their appreciation of the Hometown Hero banners that are displayed on lampposts throughout the streets of our town. Each serviceman’s banner bears his birth and death year and hence, the comment that I hear most frequently is, “Oh my God, they were just kids”. In the years preceding the inception of the Cranford 86 project, during the speeches given on each Memorial Day morning, it was this fact, among others, that would never fail to trigger my emotions, causing the hairs on my arm to stand at attention. It was a feeling so strong, that it drove me to take action to reintroduce these brave men to the new generations of Cranford residents, making sure that their faces and stories would never be forgotten. Of the forty-eight banners that have been presented so far, incredibly, twenty-five of these men were age twenty-one or younger when they died. They truly were just kids, as is the case with the hero whom I am about to introduce. Emil F. Frank was still a teenager when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II, and now it is his turn to have his story told.

A Young Man Who Could Light Up a Room

Possession of the servicemen’s military portrait is what gives our team the green light to begin the research and writing which will memorialize his life. The portrait is the most coveted element of the entire process. In Emil Frank’s case, a photo on file at the Cranford Historical Society was one of the best that we have discovered to date. Not only was it crisp and clear, but it was an image that seemed to show the genuine spirit of a nineteen year old that you would say “could light up a room”. My two children were in their late teens themselves when I started the Cranford 86 journey and seeing pictures like this only deepened my empathy for the Gold Star families who were emotionally crushed, from the loss of such shining spirits from their lives.

For many of the Cranford 86 profiles that we have completed so far, we have been blessed to have made personal connections to family members or acquaintances of our Hometown Heroes. These are people who have either approached us on their own to initiate their loved one’s story or others who we have located through our research. For the story of Emil Frank, we have made several attempts to contact Emil’s nephew, Emil Long, with no response. Born in 1948, Emil Long is the son of Emil Frank’s sister Florence, and we believe his last known address was in Florida. Being his uncle’s namesake, we had high expectations of what this connection would bring and continue to hope that it occurs in the future. In the meantime, the discovery of a folder at the Cranford Historical Society has given our story a personal touch. In the folder was a beautifully crafted three-page letter, from the 1940’s, handwritten in script. The letter seemed to be written by a family member and it detailed the life of Emil Frank. It is from these words that we learned about our brave young hero.

Just a Great Cranford Kid

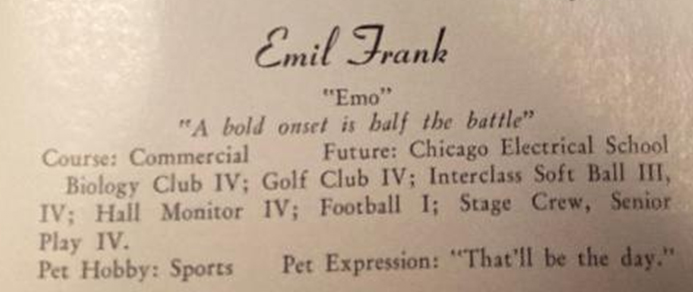

Emil was born on February 26th, 1923, to Emil and Louise Frank, a newlywed couple from neighboring Garwood. The young family moved to 426 Brookside Place in Cranford, when Emil Jr. was just months old. Our research has enlightened us to the fact that not every hero listed on the bronze plaques at Memorial Park was raised in Cranford. Nevertheless, each one is embraced and honored equally, but Emil Frank was a true hometown kid, living almost his whole life in Cranford and attending both grammar school and high school here. Early on, Emil Jr. was a baseball enthusiast involved in many after school activities. In Cranford High School he played freshman football, joined the Dramatic Society, Bowling Team, the Biology Club and the Golf Club. He was also a member of the band. After graduating with the class of 1940, Emil took employment in Bayonne as a machinist’s helper. His sights were set on becoming an electrician, with plans to attend the Chicago Electrical School. As with most high school graduates of the later Great Depression years, the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, changed many of the best laid plans. On January 31, 1942, just fifty-four days after the Day of Infamy, Emil enlisted in the U.S. Navy, leaving his job in Bayonne where he was now foreman. Emil attended basic training in Rhode Island and then advanced training for an additional sixteen weeks at Great Lakes Naval Station. He returned to Rhode Island for more advanced training at Torpedo School, in preparation to be a crew member on a destroyer. The attack on Pearl Harbor, triggered the U.S. Navy to rapidly rebuild their largely neglected collection of warships. Twenty-four new battleships, thirty-six new aircraft carriers and one hundred seventy-eight new destroyers as well as many other smaller vessels would be created rapidly, an amazing undertaking. The destroyers alone would need over 50,000 crew members. Not only were the ships filled, but they were overcrowded, an amazing American response to a call to action. An unofficial comparison that was had by a quick Wikipedia search noted that the Navy’s size from pre-December 7th, 1941 was at 337,349 sailors. At war’s end, it was an astonishing 3,793,429.

Tin Can Sailors

Our 2022 tribute book tells a detailed account of Friend Burton, a young sailor from Cranford, who served on a destroyer. It was said that an assignment to a battleship or aircraft carrier with crews of 2000 would be compared to living in a large city, whereas an assignment to a destroyer with a crew size of less than 300 would be like living in a small town. Because of their thin steel skin, destroyers were given the nickname “Tin Cans” and their crew members were called “Tin Can Sailors”. The relatively light weight of the thin-skinned, nimble warship made it sit high in the water. Its draft, or depth in the water, was shallow, making it a difficult target for attacking torpedoes, but by the same token, it was a very easy kill when struck. Mortality rates of the Tin Can Sailor were higher than in any other Naval assignment.

For nearly every Cranford 86 profile created up to now, our research has given us an idea of the physical stature of our Hometown Hero. Generally, military or school records provide us with a height and weight, but this was not the case for Emil Frank. The few photographs that were available to us, gave us the impression that as he was leaving high school, Emil was a relatively small young man. But from his military portrait, he had a larger persona, almost as if wearing his Navy uniform made him stand a little taller. One of his extracurricular activities at Cranford High School was membership in the Dramatic Society. It seemed to me that possibly the part he had chosen to play in the Navy was that of a torpedoman’s mate. He and his team were responsible for initiating the process whereby a 24 foot by 21 inch highly explosive metal projectile is hurled from a ship via compressed air, to the ocean’s surface. Then, with twin propellers providing thrust, it would travel under the waves at 25-40 knots up to 4,500 yards in hopes of sinking a German U-boat. It was a much larger role than any of his schoolmates might have imagined he’d be performing in the service of his country.

Assignment to the USS Maddox

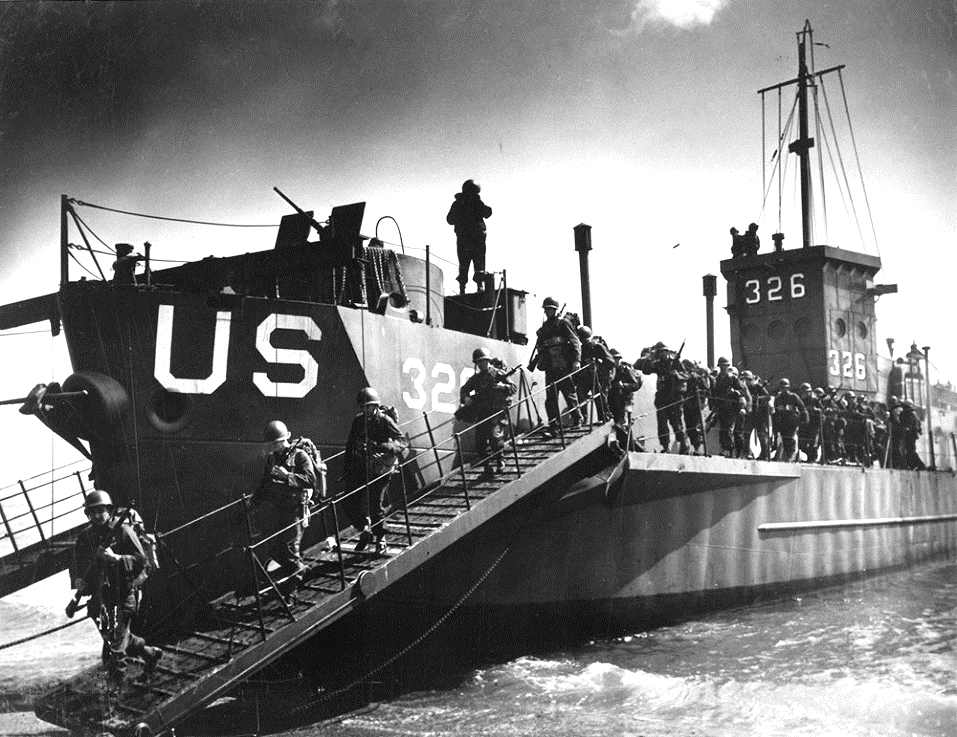

Torpedoman’s Mate Third Class Frank was assigned to the USS Maddox DD-622. The Maddox was a Gleaves-class destroyer, newly laid down from the Federal Ship Building’s docks in Kearny, N.J. on September 15, 1942. The ship’s first mission was in early April 1943, escorting fuel supply shipments from the Allied forces’ fuel depots in Aruba and Texas. Missions to North Africa and then to Ireland followed and it was reported that the USS Maddox received its first battle stars from enemy actions on one of those assignments. No battle details were available to us, except to say that Emil Frank was injured in an encounter in foreign waters and was returned to a hospital in Brooklyn, N.Y. He was able to spend some precious time in Cranford as part of his recuperation, before rejoining his shipmates on the Maddox on May 24th, again headed to North Africa. Now, the Maddox was preparing to play an important role in the upcoming Battle of Sicily at Gela. At this time, Sicily was occupied by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany and this battle would be the opening engagement of the American portion of the Allied Invasion of Sicily. Code named Operation Husky, the invasion would be the largest amphibious assault in world history up to that point, with an armada of 3,200 attacking ships, and over 500,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen. It would be the first amphibious attack ever to use huge LCT tank transport ships.

The Seventh Army, under command of Lieutenant General George Patton was to lead the ground attack on Sicily after his success over Nazi General Rommel, the “Desert Fox”, in North Africa. Patton had taken over command in North Africa after the Allies were nearly beaten there. Eisenhower and Patton wanted to follow their successes in Africa with an attack across the English Channel but were overruled by British General Montgomery and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who were not yet convinced of the abilities of the newly arrived Americans. It would be by the success in Sicily that Eisenhower and the American Armed Forces would get the nod, giving them the lead role in the Normandy invasion.

Operation Husky, The Battle of Sicily

As has become a custom of the Cranford 86 team, we like to explain the historic and strategic plans that surround the event in which our serviceman loses his life. This somewhat detailed explanation of Operation Husky explains the importance of the battle in which Emil Frank participated.

On July 5th, 1943, convoys protected by numerous U.S. and British destroyers left from Oran, Algeria on the northern coast of Africa. On July 9th a collection of Allied war ships named Task Force 81 sat in the Mediterranean Sea, some sixteen nautical miles off the Gela River, Sicily. Among them were thirteen military transport ships full of soldiers, two light cruisers, eight destroyers, including the USS Maddox. Several submarines, numerous LCI, LCT and LCS landing crafts as well as some salvage crafts. Task Force 81 was an impressive array of ships in itself, but it represented just a fragment of the staggering force of Operation Husky, which was staging for attack. There would be no pre-bombardment as would many times be the tactic in an operation such as this. The hope of a surprise attack was the intent. Not until 18:40 on July 9th was the convoy spotted by the Nazis. The Luftwaffe and Italian Air Forces released an all-out assault on the convoy, launching over 500 sorties to hamper any success by the soon-to-be attacking forces. The U.S. Army Air Force’s 12th Air Support Command planned on providing air cover over Gela during daylight hours, but about 30 minutes before sunrise, at 04:21, the first Axis bombs were dropped. The USS Maddox was on torpedo watch on the outer perimeter of the task force’s position. Thirty-seven minutes into the battle, a German Junkers Ju-88 dive bomber, on an attack dive aimed at the Maddox, dropped its 4 bombs. The first bomb hit the water behind the destroyer. The second two bombs struck the fantail-shaped back platform, causing an enormous fireball, the fourth missed and landed in the water next to the ship. It is believed that the racks of depth charges on the fantail aft deck were struck by the second bombs, hence the huge fireball, causing catastrophic damage. USS Maddox DD-622 with a crew of 284, including our twenty-year-old Emil Frank, sunk in ninety seconds. A minesweeper, the USS Sentinel PC-621, was also sunk during the same attack. A huge tank landing craft LST-313 which was struck by bombs during the attack, was damaged badly, but made it to shore to unload its cargo of tanks before burning on the beach. The light cruiser USS Savannah shot down a Ju-88 at 05:14, not believed to be the same dive bomber that attacked the Maddox.

Where was Emil at this Fateful Moment?

Without question, the most difficult part of what we do is to describe the events in which our Cranford hero loses his life. While relating the last moments of the USS Maddox, I asked myself, where was Emil in all of this? Based on previous Cranford 86 stories involving naval battles, we understand that every crew member has a daily job and also a battle station position. With his ship under fire, I envision Emil, in place, at the torpedo launchers, which were located on the deck at midship. With the crew size of a destroyer being relatively small, I imagined that no matter where he was, he was surrounded by friends and crewmates, men that he knew. Perhaps this thought provided a small amount of comfort to his family members when they heard of the tragic episodes of that fateful day.

Reading this battle story, I wanted to make sure that I knew the specifics about what distinguishes a dive bomber from other attacking bombers. Side research revealed that dive bomber sights its target as it descends to attack, like a suicide pilot. But unlike the Japanese kamikaze, in the Pacific battle theater, which crashes into its target using its plane as the bomb, a dive bomber releases its bombs and then pulls out of its descent, letting the bomb load continue the course of the plane and strike the target. My naivety of many military terms is often commented on by readers in two ways. Some with advanced military knowledge will tell me that I over explain simple situations. Others, like me, who are still learning, thank me. A large part of our readership, we have found, are new followers of America’s war history. They have indicated that terms mentioned casually in other battle stories, without definition, have left them wondering. We try to please all of our readers and always welcome your comments.

The Fine Tuning of an Amphibious Landing

The challenges experienced by Operation Husky on July 10th, 1943, began with gale force winds of thirty-five knots that created twelve foot seas, causing widespread seasickness and many navigational errors. The plan of a highly complex, full-fledged air attack was largely compromised due to weather. Only 200 of the 3,400 paratroopers reached their targets behind enemy lines, and gliders planned to place fighting units in strategic locations were not able to accurately land in the predetermined locations. One third to one half were believed to have landed in the Mediterranean. These conditions were similar and even worse than those experienced by attacking Allied troops at Normandy beaches, on the difficult morning of D-Day, which still lay eleven months ahead. What was learned from Operation Husky is believed to be responsible for the successes of D-Day, June 6, 1944. The course of World War II and world history was redirected from that day forward. The accomplishments of Generals Eisenhower and Patton in the 38-day Allied Invasion of Sicily proved the Americans to be worthy of the lead in the upcoming battles in the Mediterranean and ultimately the English Channel at Normandy. See the online story at Cranford86.org for links to more details of the battle of Sicily.

Operation Husky, a Success?

Many historians say, even though smaller in scale, Operation Husky was more complex in its strategies than Operation Overlord on D-Day and was a success for the Allied forces. However, some critics state that the Allies lack of coordination of attacking air forces allowed the retreating Nazis to move 100,000 troops and 10,000 pieces of equipment out the Sicilian back door across the Strait of Messina to the mainland of Italy, a major strategic failure. The Nazi forces were in a vulnerable state and could have been completely eliminated there. Instead, the Allies would face them again in Anzio, at another amphibious landing attack that would happen in January 1944. Some even say that the Nazi strategists deserve credit for realizing that they were outmanned and destined to experience a great loss in Sicily. By retreating to fight another day they could have been considered the victor. Regardless of the conflicting opinions of history pundits on the topic of success or failure, all agree that Operation Husky served us well to prepare the Allies for the most pivotal event of WWII, which was yet to come at Normandy. Some WWII historians still consider Operation Husky to be the turning point in the war, with Sicily being the first piece of Nazi-occupied European land to fall to the Allied forces.

She Went Down in Ninety Seconds

Immediately after the demise of the USS Maddox, a landing craft that witnessed the sinking in the darkness before dawn, reported that there were no survivors. However, seventy-four crew members were miraculously found afloat by a tugboat that witnessed the fireball from a distance. The incident reports claim they were afloat for 17 hours.. After persevering through the perils of the attack and sinking of the Maddox, survivors then endured numerous strafing attacks from Italian Air Force and other Axis planes, as well the threat of the attacking predators in shark-infested waters. The USS Maddox, DD-622, received the unfortunate distinction of having been the fastest sinking U. S. warship to be lost in World War II. The ship’s commander, Lt. Commander Sarsfield, went down with the USS Maddox. He received the Navy Cross posthumously for his documented actions which saved the lives of many crew members during the ninety-second abandon ship operation. Second only to the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross is presented to marines or sailors for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force.

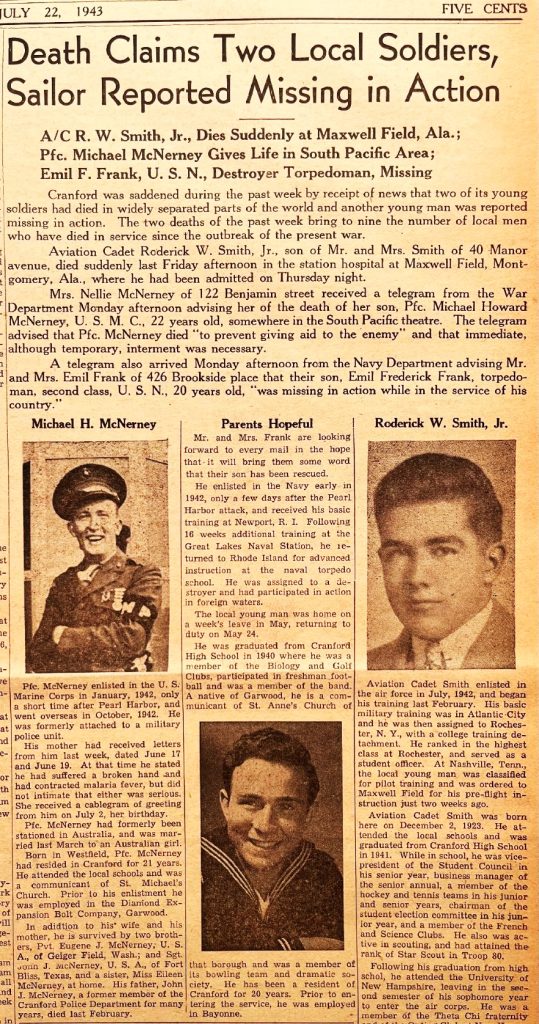

Torpedoman’s Mate 3c Emil Frederick Frank Jr. was reported missing in action on July 10th, 1943. News of Emil’s status was reported on the front page of the July 22nd issue of the Citizen and Chronicle. The article read, “Parents Hopeful” stating that “Mr. and Mrs. Frank are looking forward to every mail delivery in the hope that it will bring them some word that their son has been rescued”. Emil’s family waited a full year in what must have been unimaginable anguish. Finally, Emil was reclassified as killed in action and lost at sea, and one wonders how this family could even begin to heal. Emil Frank’s name is engraved at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy, on the Tablets of the Missing. His naval career was just a short eighteen months. In addition to the Purple Heart, he was honored with the American Defense Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the American Theater Campaign Medal, and the Expeditionary Medal (Navy). If Emil were alive today he would be one hundred years old.

The USS Maddox DD-622, now with two battle stars, was struck from the Navy’s list on August 19, 1943, just 11 months after its launch, still with its first coat of gray paint. In October that year, the third USS Maddox was laid down, with new bow number DD-731. It went on to historic tours of duty in the remaining two years of WWII, and in the Korean and the Vietnam Wars.

Emil was survived by his father Emil F. Sr. and his mom Louise Frank, nee Hartman and two sisters Louise Frank Bohman and Florence Frank Long, all of Cranford.

Emil Frank was just a kid when he volunteered for a task, the enormity of which most of us cannot even grasp. As captured in the treasured image of his smiling face, he will remain forever young, but he became a grown man in every sense of the word. The Cranford 86 team will continue to search for a family member of Emil Frank. But, in the interim, he has a family here in Cranford. Everyone who takes the time to read about Emil’s sacrifice, or who gathers with us on Memorial Day morning, or who glances up at his banner in town and whispers his name, is Emil Frank’s family. If you carry gratitude in your heart for what Emil did for us, you can be his family too.

The banner of Torpedoman’s Mate 3rd Class Emil F. Frank was sponsored by Rosemarie D’Alessandris Boczon. Rosemarie is the niece of Augustine D’Alessandris, one of Cranford’s 86, also lost in WWII. After working closely with her in the telling of her uncle Augie’s story, Rosemarie was anxious to help us to continue our work and volunteered to sponsor a banner of an upcoming story. The cheerful military portrait of Emil caught her attention and made her hero selection an easy choice. Emil’s banner will be dedicated at Cranford’s Memorial Park on Riverside Drive and Springfield Avenue on Memorial Day morning, May 27th, 2024, following the parade.

The mission to introduce every man whose name is engraved on our town’s memorial park’s honor roll will continue until we put a face and a story to every one of the Cranford 86. Currently there are many files that have no picture or personal information, to complete our work, we count on Cranford townspeople that have knowledge of the heroes that up to now, are unknown to us, to come forward. Go to Cranford86.org and see the spreadsheet of heroes. For more information about the Cranford 86 project, email us at info@Cranford86.org.