Meet PVT Steven A. Mager,

WWII Infantryman, One of Cranford’s 86

Written by Don Sweeney, Co-written and Proofread by Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault, research by Stu Rosenthal with Military Expertise and

Proofreading by Vic Bary

As our Cranford 86 team moves into our fifth year, we are proud of what we have accomplished so far. We are steadily moving closer to our goal of introducing every soldier on our town’s honor roll to the residents of our wonderful community. The work that we are doing reminds us all that a place as special as Cranford was bestowed upon us by some very brave soldiers who sacrificed so much. We present yet another story about one of those men who gave up everything, so that other Americans could live a life of freedom.

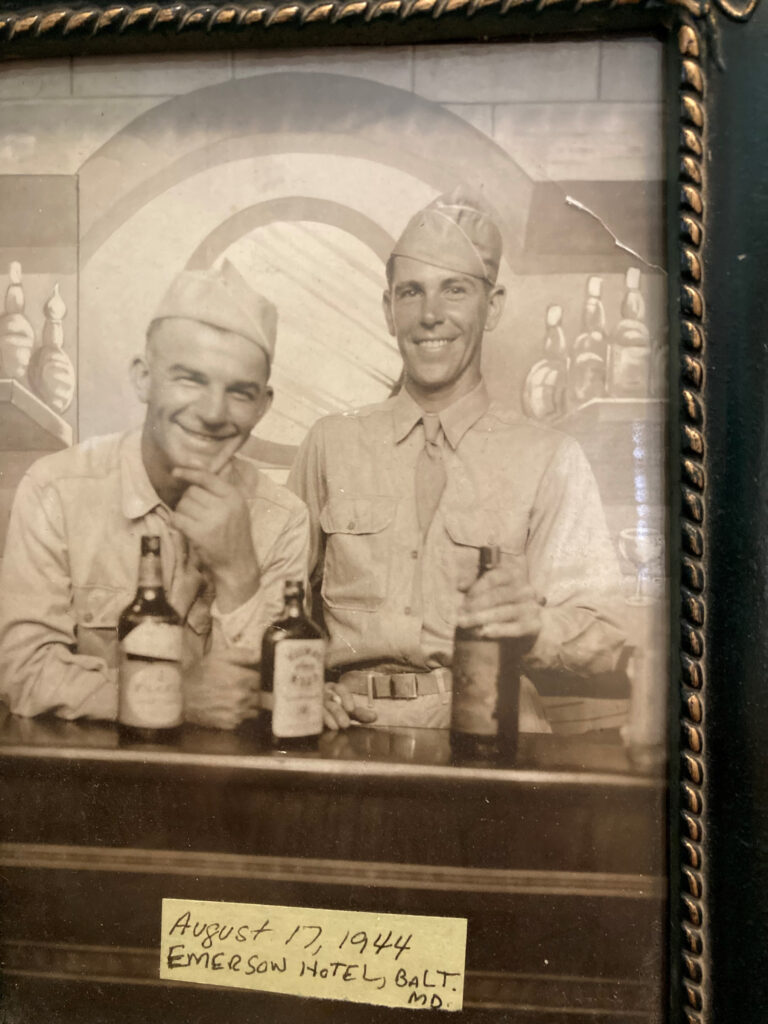

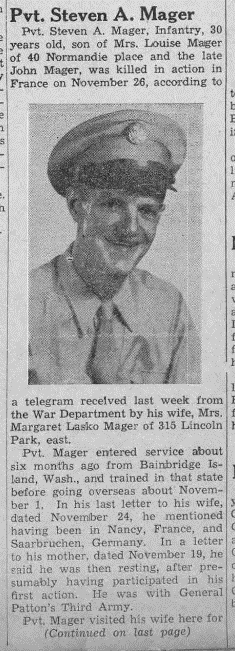

Shortly after Memorial Day 2021, we were contacted by Dawn Mager, granddaughter of PVT Steven A. Mager. Dawn’s grandfather died in France, while serving our country in World War II, and she wanted to know if we could help to tell her grandfather’s story and honor him with a street banner. We are always thankful when family members reach out to us and forming a relationship with them has become one of the most meaningful parts of what we do. Dawn told us that her father, Kenneth Mager, who was born two months after his father Steven was killed in action, still lived in Cranford. We explained that the first thing we would need was a suitable portrait to start the process. She told us that her dad had her grandparents’ wedding photo and that he could bring it to my home right away. My doorbell rang a short time later and I saw a familiar face through my storm door window. Dawn’s father, Kenneth Mager was someone from town with whom I had chatted briefly from time to time. I thought to myself, we advertise and request that if anyone knows a Cranford 86 member, they should come forward. Amazingly, for years, a son of one of our heroes and I knew each other, albeit a casual acquaintance, and we had not made this connection. Without much information to go on from the start, we knew that this story might be a difficult one and it sat on our back burner, disappointing the family when we did not have anything for Memorial Day 2022. Dawn called us in early January of this year, wanting to know if she should book her flight to New Jersey for Memorial Day 2023. This quickly had us rewrite our hero line-up, and we assured her that we were a go for her grandfather’s story in 2023. Dawn got us in touch with her father’s older brother Richard, who lived in New Jersey. Richard, a retired teacher like his brother, arrived at my home with a stack of family papers. The information that he provided allowed us to further our research and tell Steven Mager’s sad and heroic story.

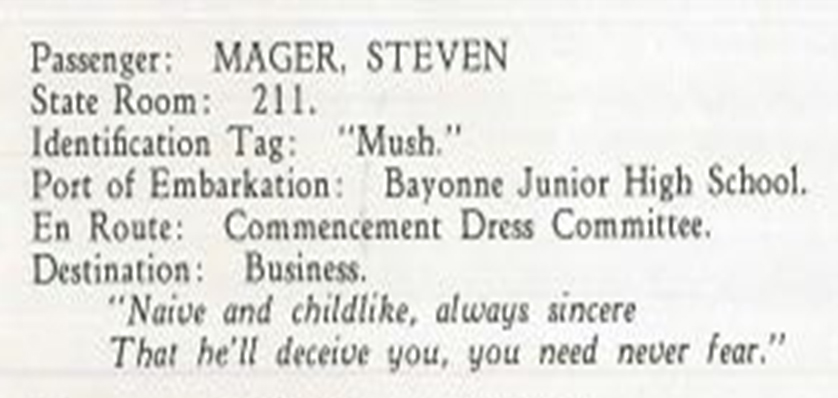

Steven Adolf Mager, the son of Louise and John Mager, was born in Bayonne. He attended school there and then studied for a year, nights, at NYU. Fond of all sports, he excelled at swimming, which he taught at the YMCA in Bayonne. He became employed as a district manager by the Texaco Touring Service at the age of 21, which amazingly allowed this young man to see and live in Florida, California, Colorado and Yellowstone National Park. Son Richard explained to us that Texaco Touring was a travel service for motorists who were planning excursions on America’s growing network of highways. We believe that Margaret Lasko, Steven’s girlfriend, also from Bayonne, travelled with him for some time. In 1941, they were married in Denver, Colorado. Steve and Maggie set up their home on picturesque Bainbridge Island, Washington, in the Puget Sound, just off the Seattle coast. The headlines of December 7th, in that same year shocked the world and this young couple certainly could not have imagined how the news was going to affect their dreams of a future together. Nevertheless, they proceeded on with their lives, welcoming their first son Richard on August 10th, 1942. The threesome enjoyed a year and a half together until Steve received his draft notification and was ordered to report for duty in May of 1944. Maggie was then two months pregnant with their second child.

At this point in time the Selective Service System was drafting young men at an astonishing rate. One hundred and sixty thousand soldiers landed in Normandy in June of 1944. But to further liberate Europe, General Eisenhower needed more than ten times that amount to continue forth and release the grip that the Nazis had on our world. The pool of eligible candidates for the draft had to be enlarged considerably and its scope was now widened to include men like Steven, over the age of 30, with children at home. During the research of Steven Mager’s story I realized that it had a strong personal connection to my own family. My maternal grandfather, 33-year-old Herman Bachmann was inducted at this same time. He left a family in Jersey City, which included his 8-year-old daughter, my mother. Additionally, Steven and my grandfather both served in the 80th Infantry Division which, as we will learn, made its way through the most grueling battle conditions of Europe.

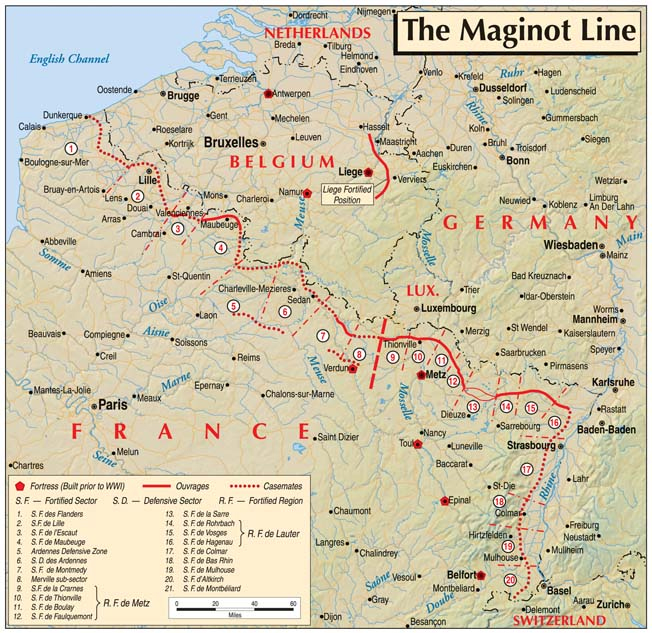

General Horace McBride, under the command of General George Patton, was ordered to organize three regiments of 1,500 soldiers each. The 317th, 318th and 319th Infantry Regiments of the prestigious 80th Infantry Division, a part of Patton’s 3rd Army, began their entry into France via Omaha Beach on August 2nd, 1944, 2 months after D-Day. Initially composed of draftees from the Mid-Atlantic states, the 80th was nicknamed the Blue Ridge Division. Well known since their incredible success in WWI, their motto was “Always Moves Forward”.

The Cranford 86 project has already told the story of three infantrymen from this same time period, Cecil Spittler, Arthur Galvin and William Hinkle (their stories at Cranford86.orggive additional background of the history surrounding this time period). All were in training around the same time, and all headed across France to different parts of the German border. We had little information about the training records on PVT Mager, except a one line entry in his obituary saying he trained in the state of Washington. Much to the dismay of anyone researching an Army veteran, a 1973 fire at the archives destroyed 80% of Army personnel files. If family members cannot provide us with specific information, it takes weeks to try and piece together a soldier’s tour of duty.

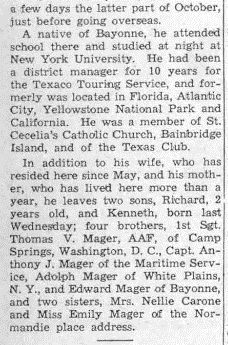

A large amount of background for me was had by watching dozens of online video interviews with other soldiers that were inducted into the 317th, 318th and 319th Infantry Regiments in the fall of 1944. They described a rapid advanced training process at the California-Arizona Maneuver Area in the Mojave Desert and several other places. We found that their stories aligned with the timeline that we were building for Steven Mager, starting when he reported for duty and until his departure for Europe. Compare the accelerated training that Steven’s unit received, a total of only four months as opposed to the two years training given to Arthur Galvin and William Hinkle. Before departing from the New York ports on their way to Europe, the troops of the 80th Infantry Division were staged at either Fort Dix or Camp Kilmer, both in New Jersey. Steven’s wife, now seven months pregnant, had moved in with her sister at 315 Lincoln Park East in Cranford, today’s Kahlcrest Condominiums. This aligns with the obituary in the Cranford Chronicle which documents that Steven had a three day visit with family in Cranford at the end of October. Thankfully his travel schedule allowed for some precious time spent with Maggie and young son Richard before going overseas. The details of Steven’s movement to France were not available to us from family records. So again, the video interviews of many members of the 319th and their sister regiments gave us a vision of the travels of the nearly 5,000 men, as they moved into the theater of battle in France. Trains moved the men to Hoboken. Then, ferries transported the regiments across the Hudson, to the slips on the west side of Manhattan where they boarded converted ocean liners, including the Queen Mary. The men reported that onboard, they were packed in like sardines. At sea, they were escorted by war ships which surrounded them, and armed fighter planes above. The ships delivered the 80th Infantry Division to Glasgow, Scotland, where night trains carried them 430 miles to Southampton, England. Then, aboard Landing Crafts Infantry (LCI’s), crossed the English Channel, joining a process which had started in August. Steven’s 319th Infantry Regiment, Second Battalion, Company A, with approximately 175 men, landed on Utah Beach in France on November 1st. To help compensate for the destroyed Army personnel files, Cranford 86 purchased a logbook that contained the Army Morning Reports of the 319th Infantry Regiment. We also located an online publication called “Forward 80: The Story of the 80th Infantry Division”. These served as guides as we tried to follow Steven Mager’s 400 mile path through the French countryside. After being defeated in Normandy, the Germans quickly retreated and reorganized behind the decaying Maginot Line. The Maginot Line consisted of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapons installations built by France, after World War I, to deter any future invasions by Germany. Using it to their own advantage, the Nazis quickly refortified the overgrown pill boxes, mini fortresses, and dragon teeth barriers. Meanwhile the Allies gathered their forces and supplies, preparing to chase after the former French occupiers. Surrendering German soldiers had revealed Hitler’s strict orders to German soldiers that retreat was not to be considered. They were to fight to the death and die at their posts. It was said that the men of the 80th infantry were doing everything in their power to ensure that that was indeed the fate of each and every Nazi.

The Blue Ridge Division became a part of XII Corps. A Corps is a combination of complimentary battle units, in this case, infantry, engineering, armored (a tank unit) and an air support unit. XII Corps’ commander was General Manton Eddy, who led his men across France with several missions. They were to “mop up” the remaining German resistance, which still were holed up in many French towns and villages. XII Corps would also support the engineers as they repaired infrastructure. In a strategic move to stop German fortification of Normandy, many roads and bridges had been destroyed by our own bombs prior to D-Day. More damage was done by the retreating Germans, after their defeat there. Working infrastructure was essential to get supplies to attacking forces attempting to invade Germany, and also to bring additional fighting forces to the front lines. Commanded by General Patton, Cranford’s Arthur Galvin in the 4th Armored Division with 10,000 soldiers, had chased the enemy through the French countryside in September of 1944, reaching the Metz region in one week. With this in mind, we can see how Steven Mager’s unit was able to move so quickly inland, so soon after their arrival, right into hostile territory. A letter to his mom indicated that he was involved in fighting within the first weeks of November. The American troops of XII Corps were under constant attack from artillery and machine gun fire as they quickly moved towards the front line. Many Germans were still dug in, creating pockets of resistance. Some gave up easily, but in many towns, violent battles were still to be fought. Encounters with lethal Panzer units, artillery fire from German armored divisions, as well as sniper fire, mines and booby traps, made some days very difficult and deadly. While other days, the Allies were met with massive surrenders, sometimes leaving thousands of prisoners of war to be dealt with. Morale was high, as our forces were encouraged by the feeling that the war might soon be over. The French citizens for the most part, were welcoming, but some, called “enemy civilians”, were still siding with their former occupiers. Many times, the deserting German soldiers were dressed in the French civilians’ clothing, trying to blend in with the townspeople.

Several online articles painted vivid accounts of the daily perils of XII Corps, from early November 1944. An incredible amount of rainfall went on for weeks throughout this crucial time period, causing flooded and impassable muddy roads which plagued the rain-soaked GI’s. Some rivers were running 10 feet over their banks creating horrendous living conditions for the soldiers. The logbooks mentioned several times that no rain gear or galoshes were issued, leading to rampant cases of trench foot. That region of France was laced with rivers of all sizes, and with the high water levels, they were all raging. Traversing those rivers with small inflatable rafts was treacherous, there were many losses due to drowning. Our military logbook, which lacks any colorful speech, filled in the gaps to our story by telling us the exact company and battalion of each action. Using both the journalist’s colorful depictions and the stark facts of the Army Morning Reports was like working a military jigsaw puzzle, with the picture becoming clearer as each piece was inserted. The 319th Infantry Regiment, in early November, was charged with the mammoth task of setting up a bridgehead across the swollen Sielle River in the Metz/Nancy region. The river was France’s longest and was situated beyond the towns of Letricourt and Abaucourt along the Delma Ridge. Control of the ridge was one of General Patton’s most important objectives. The bridge that formerly spanned the Sielle had been destroyed. So a newly engineered pontoon bridge that would carry trucks, armored vehicles and tanks across the river was to be constructed. Letricourt and Abaucourt were occupied by a considerable military presence from the 48th German Division. In addition to enemy troops, the roads, small bridges, and vineyards were full of mines and booby traps with foxholes lining the streets. All three companies of the 319th Infantry Regiment were in place, as were the 702nd Tank Battalion, the 305th Engineer Combat Battalion and others. The result of this battle illustrated how the different units of the XII Corps worked in conjunction to accomplish their mission. The attack commenced in the early morning under the cover of a dense fog. Artillery, mortar fire and air strikes softened the resistance then heavy bazooka and grenade warfare took place in the streets; the towns were U.S.-controlled by early evening. Many munitions were seized, 162 prisoners of war were taken and 148 enemy KIAs were reported. Interviews with the prisoners afterwards confirmed that they were taken completely by surprise. With the raging state of the river, the Germans felt that it was unpassable and that no attempt at crossing would ever take place. Amazingly the 305th engineers had a pontoon bridge in place in short order.

As they traversed a dozen or more rivers, similar reports were logged by the three sister regiments. The XII Corps continued its march toward the 450-mile-long Maginot Line, with its 43 forts and 128 heavy guns, some mounted in revolving turrets. The Maginot Line was built by the French to defend itself from the Germans, so more of the guns and fort placements were facing Germany, not France. The Germans’ small pockets of resistance, even though well-armed with their fierce Panzer tanks, were no match for the immense might of the travelling force of the XII Corps. General Patton’s 3rd Army had 250,000 troops in the region, the Germans 86,000. The Americans also had a huge advantage in artillery and air support. Up until now the Americans had been running short on ammunition and fuel, but fuel just arrived on November 1st, so ammunition was the only element that concerned General Eisenhower. Thankfully, in many face-offs the massive U.S. strength displayed, often caused a rapid German surrender. Every interviewed POW confirmed the earlier reports of the Fuhrer’s orders of “no retreat, no surrender”. On November 17th the three regiments of the 80th Infantry Division converged on St. Avoid and Longeville. This was the coal center for the Nazi machine. Its taking was heralded by the New York Daily News as the greatest loss for General von Rundstedt, the campaign’s commander in chief.

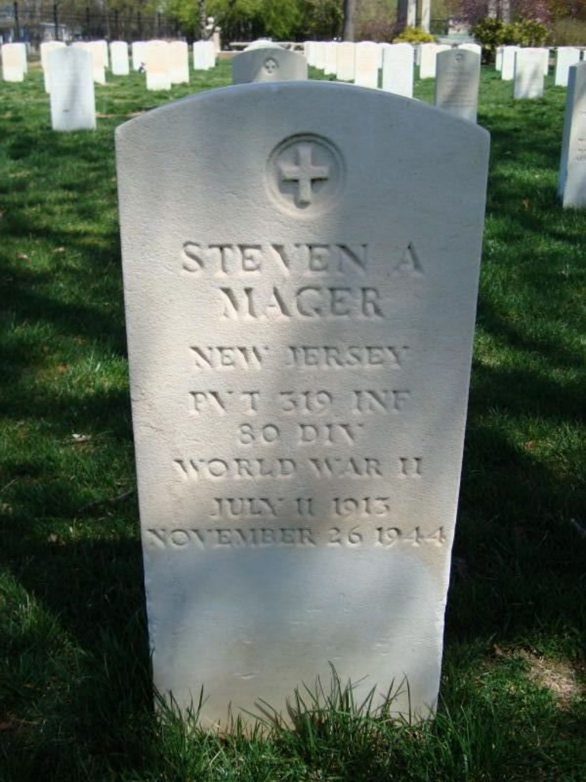

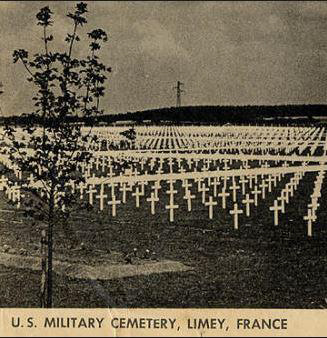

According to his obituary in the Cranford Chronicle, Steven wrote a letter to his wife Margaret on the 25th of November. Many times, as in the book We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, before a major, dangerous encounter, a commanding officer recommends that the soldiers under his command write home. I felt that may have been the case here, for the 26th of November was a big day as the charging forces of XII Corps would cross the Nied Allemande River to conquer the mining town of Faulquemont. To the rear of the town lay their first view of the Maginot Line. The armed fort at Faulquemont was taken in record time by the 319th Regiment. Then, in a well-orchestrated attack, the entire collection of Patton’s troops went on to take seven other forts and 13 pillboxes that lay between them, in what was described in the logbook as a crashing powerhouse drive. It must have been a sight to observe. A captured German commander whose battalion was crushed in the attack, described the assault as remarkable. He was amazed by the skillful utilization of tactical advantages, and the cooperation of infantry and armored units along with the supporting heavy weapons. The very sad news of the day was that despite the victories, there were many casualties and Killed in Action. It is here that we believe our Hometown Hero, PVT Steven A. Mager, was part of the losses. In his letter home, Steven stated that he was in the area around Nancy, France and Saarbrucken, Germany. This aligns with our research, as Faulquemont is just a few miles from the city of Nancy. The German city of Saarbrucken is six miles behind the Maginot Line at Fort Faulquemont. It had only been 26 days since he arrived in France.

A passage from an article used for our research paints a vivid picture of the conditions caused by the weather during these incredible battles.

“Eddy’s XII Corps troops fought weather conditions just as determined to defeat them as the Germans. After a partial clearing on the first day of the offensive, the temperature in southern Lorraine dropped precipitously on the second day of the assault. For the next week, precipitation alternated between snow and rain. As a result, U.S. troops, still clad in summer uniforms, found themselves soaked to the bone as they trudged forward along muddy roads past farm fields where manure heaps burned their nostrils with an acrid smell. In some places, troops marching overland found themselves slogging through mud up to their knees. As a result of the conditions, hundreds of cases of trench foot were reported each day. XII Corps reported 3,000 cases of trench foot during the November offensive.”

Of the total number of soldiers serving with the 80th Infantry Division during its time in Europe, there were reports of 3,500 killed, 12,484 wounded, 488 missing and 1077 POWs. Just days after the striking victories at the Maginot Line into the commercial Saar River Valley, the 80th Infantry Division was called to Luxembourg, Belgium approximately 100 miles west, where they travelled through the night on military transport trucks. Here they aided in the defense of the last offensive strike of the Nazi forces in the Battle of the Bulge. General Patton was credited with the strategy that thwarted Germany’s last ditch effort to stop the Allies from advancing into Germany. From there the 80th crossed the Rhine River into Germany and then into Austria where it became the force that liberated the Ebensee concentration camp.

Back in New Jersey, with the help of a family member who was a Navy veteran, Maggie found a home for herself and her two boys in Winfield Park. A federal housing community created between Cranford, Clark and Linden, Winfield was aptly named for the projected outcome of the war, Win-field. Local manufacturers like General Motors and the Kearny shipyard had re-engineered their facilities to support the war efforts. I was aware that many of their workers lived in Winfield during wartime. It was nice to hear that the government thought enough to use the 145-family housing development to offer a safety net to the families of our fallen. Richard shared with us that his mom was able to care for them full time, never having to return to work. Her Social Security stipend and a generous supporting family made ends meet throughout their childhoods, attending Catholic schools as well as onto higher education.

Steven Mager never lived in Cranford and his wife ended up here out of necessity, needing support from family while Steven was away. At the time of Steven’s death, Margaret’s address of record was in Cranford, and this is how Steven has a place on Cranford’s Roll of Honor. We gladly and proudly accept him as our own and will certainly share his story with his hometown of Bayonne. We are very grateful to the Mager family for calling our attention to their loved one and sponsoring his banner. It has given us the opportunity to learn about this brave and patriotic American who left his young family when called upon and joined the fight against tyranny in our world.

Inquiries made to my own family, when I realized that PVT Mager was in our grandfather’s division, paid off. My uncle Bob, living in Georgia, made my day. In 2001 he sat down with his dad, Herman Bachmann, and interviewed him about his WWII experiences. My grandfather’s recollections paralleled the dozens of video interviews that I had viewed this past month. His regiment was a sister regiment of Steven’s, the 317th and he was in Company A, 1st platoon. Now knowing that information, I can paint a similar picture, just as we did for Steven Mager, of my grandfather’s tour of duty. He left the battlefield on November 11, 1944, when he was injured by shrapnel in his left arm, that had him laid up in a French Hospital for five days. Upon his release, they realized that his feet were badly swollen, and his size nine boots needed to be replaced with size twelves. He was diagnosed with trench foot and sent back to England for treatment.

The numerous stories of brave soldiers crossing France to accomplish a similar goal are starting to dominate the Cranford 86 chronicles. Even as I write this, my co-writer Janet Ashnault is deeply dug into the facts and stories of Anton Hascek. He was another infantryman committed to the same effort as the four GI’s that we have mentioned here. With the stories of 31 more of our Cranford 86 WWII servicemen left to be told, I am sure that we will once again be taken back to the battlefields of Europe. Each story that we write, rediscovers the memory of these brave men from our little town in New Jersey. I often think of all the untold stories across America that are slipping away as time goes by. I hope that our project might inspire other towns to take on the same task as we have, for their own Hometown Heroes.

As always we ask, if you have any information or know a family member of any of our Cranford 86, please contact us at info@cranford86.org. We also encourage every reader to follow us on our Facebook page, which is our project’s connection to the community. We always like to hear comments about our articles and encourage interaction and financial support.