By Al Shipley, City Historian and Rahway Library Research Consultant

In the fall of 1906, a newly arrived resident made the following observation on the day of an election, “Rahway is the worst place for politics I ever struck. For its size, I don’t believe there is any other town or city in the state that can begin to touch it. It is politics, politics, politics.” On more than several occasions throughout the city’s history, demonstrations for and against parties and individuals have overtly illustrated the passions of its politically astute citizens. One such occurrence took place during the presidential campaign of 1884 when the men of Rahway, in a unique and humorous way, expressed their opposition to a woman who was running for President of the United States.

Thirty-five years before women were granted the right to vote, a New Yorker named Belva Lockwood took the very bold step of accepting the nomination of the National Equal Rights Party, thus becoming the 1st woman to appear on an official ballot for president (back in 1872, Victoria Woodhull ran a limited campaign for the office). Ms. Lockwood was said to have stated, “I cannot vote, but I can be voted for.”

Ms. Lockwood, a teacher and lawyer, had spent most of her life working to improve the status of women while fighting against all forms of discrimination. Her positions were in line with those of the National Equal Rights Party which advocated equal rights for women, African- Americans, Native Americans, and immigrants.

From the outset of her campaign, she received little support and much criticism. Most newspapers were opposed to her candidacy and if they mentioned her campaign at all it was lampooned with both light-hearted and sarcastic humor. The Atlantic Constitution, for example, referred to her as “Old Lady Lockwood” and warned their gentlemen readers to be wary of the dangers of “Petticoat Rule.”

In a politically active city such as Rahway, it was almost a certainty that the men of the place would take an interest in the Lockwood candidacy and wage a protest, albeit in a humorous vein, to show their disapproval. A month before the election, a group of men met in a room above the post office and formed the Belva Lockwood Club. It was during that meeting that the club would make their plans to stage an unusual street parade as a way to poke fun at the candidate and to ridicule the very concept of a woman running for the highest office in the land. The parade would turn out to be an event that would be remembered in the city for many years to follow.

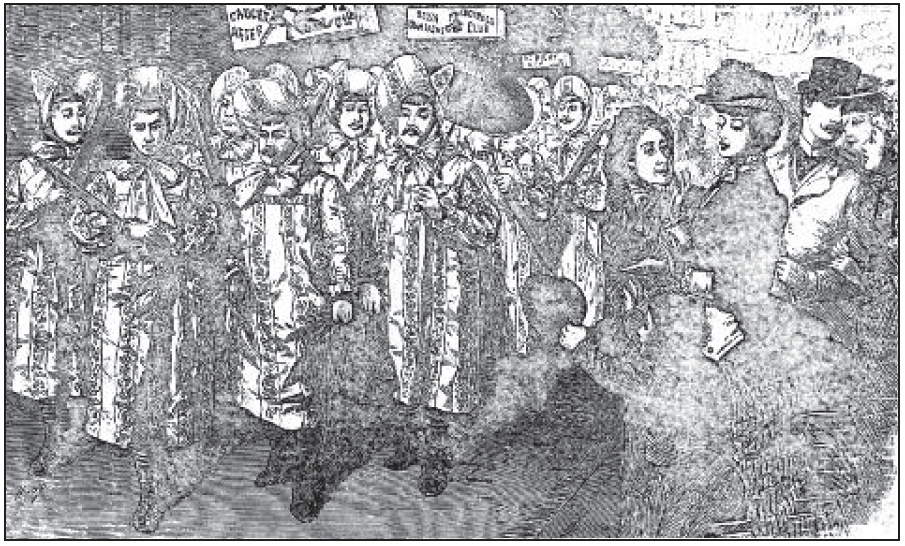

By Monday evening, October 20, news of the parade had spread and the city was alive with people, not only from Rahway, but also from adjacent cities and towns. At an appointed signal, approximately 70 men began their march through the streets, each one outlandishly attired in Mother Hubbard dresses, complete with bonnets, parasols, and striped stockings. A good natured, rotund member of the club who represented Ms. Lockwood was carried along the route in a horse drawn carriage as her attending footmen playfully regarded her with the obeisance reserved for royalty. When the “ladies” reached the home of one of their leaders, the procession halted and satirical letters were read that were supposedly sent in by Ms. Lockwood, her running mate, her Republican opponent, and the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland. As the bogus letters were read, a loud and hearty cheer resounded. A local paper reported that, “The line of march was a long one and the procession created considerable amusement for the many citizens who lined the streets.”

A week after the parade in Rahway, the club was invited to Elizabeth to march down Broad Street. That city greeted the marchers with music played by a brass band, the popping of Roman candles, and the glare of red lights emanating from lanterns carried by many of the spectators. A great crowd of people witnessed the parade which was followed by a reception at the Armory.

In the election itself, Ms. Lockwood received only 4,149 votes, all coming from the six states which allowed her name to appear on their ballots.

(above) The Belva Lockwood Club parade as illustrated in a popular publication of the period.00