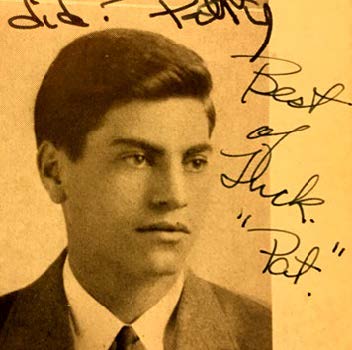

In a casual photo booth portrait, Patrick Castaldo is captured in a pose that is reflective of the memories that niece Patricia has of her uncle.

Meet Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class Patrick P. Castaldo,

USS Indianapolis Crew Member, One of Cranford’s 86.

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal,

Military proofreading by Vic Bary and editing by Janet Ashnault.

The novel In Harm’s Way, by Doug Stanton, is said by many to be the most extraordinary written account of the US Navy’s worst open sea disaster. It tells the harrowing tale of the USS Indianapolis, a 610-foot Portland-class heavy cruiser that was hit by two Japanese torpedoes in WWII and sunk in just twelve minutes. Cranford High School graduate, Patrick Castaldo of 103 Lincoln Avenue was on board the Indianapolis on that fateful day. The strike occurred in the early morning darkness and of the 1,197 men on board, only 317 would be rescued four and a half days later.

As our mission continues to provide a face and a story for every name on the bronze tablets at our Memorial Park, we are honored to tell the tale of yet another brave young man who answered the call to duty, never to return to Cranford to enjoy the freedom that his courage delivered.

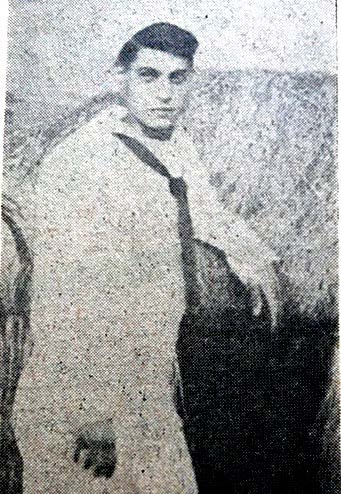

Described by his family as a fun-loving, good-looking guy with a great personality, this photo seems to capture those qualities in Patrick.

Patrick P. Castaldo was born in Bayonne, NJ on October 3rd, 1924, the ninth and youngest child of Italian immigrants, Assunta and Pasquale Castaldo. He went to Bayonne schools until he reached high school. His father was not happy with the crowd with which Pat was surrounding himself. Pasquale reached out to his eldest son Neil, a young doctor starting a practice in Cranford, and asked if Patrick could come to Cranford and live with him. Neil and his young wife Loretta welcomed younger brother Patrick with open arms and enrolled him in Cranford High School. At the time Dr. and Loretta Castaldo had a one-year old daughter, Patricia, with whom we have been in contact with since the Cranford 86 project started three years ago. Patricia Castaldo Hobbie has vivid memories of her uncle as he was her babysitter throughout his life in Cranford. She told us about her Uncle Patrick’s unique nickname that was given to him by her dad, Dr. Castaldo. Her dad said that Patrick really perked up at the sight of food, especially when nearing the refrigerator. Therefore, to everyone in their household, her uncle was known simply as “Perk”, and was rarely called by any other name. It was just Perk, not Uncle Perk nor Perky.

The living arrangements crafted for Patrick by his dad seemed to work out wonderfully. Patrick assimilated nicely into Cranford and became a good student at Cranford High School. He was active in sports as the track and cross-country manager throughout all four years, and then played on the varsity basketball team as a senior. Patricia was only age 4-6 during this time, but amazingly she was able to remember many personal details about her uncle. She recalls Perk as being a good-looking, fun-loving guy with a great personality. She told us that Perk’s girlfriend, Carol Nielsen, would sometimes join him in his role as her babysitter. Patricia grew up to become a teacher at Sherman and Hillside Avenue schools. Her uncle’s story was not the first time that she contributed information to the Cranford 86 project. As a teacher to Joseph Minnock, Vietnam War veteran and the first Cranford 86 honoree, she provided priceless input about Joe’s early life.

Patrick P. Castaldo as he appeared in the 1942 Cranford High School yearbook the Golden C.

Patrick was a graduate of CHS Class of 1942, making him a senior when the attack on Pearl Harbor took place. Some 60 percent of the men and many of the women from that class enlisted after graduation or before. Patrick Castaldo did so on September 3rd, 1942 and was shipped out for training to Great Lakes, IL, before heading to Mare Island near San Francisco for two weeks. Since the attack on Pearl Harbor, over three million military personnel had passed through Mare Island. It was said to be like a Wild West town where much steam was released by soldiers and sailors on liberty. Patricia recalls late-night phone calls from Perk, likely placed from Mare Island during that time. Her uncle would ask her dad to send money and would be promptly denied. It would be Patricia’s mom, who was very fond of her brother-in-law, who would secretly wire him the cash. Patricia mentioned that her uncle was known to love a good time and she had no doubt that he was at the center of all the fun that Mare Island had to offer.

On November 8th, 1942 Patrick Castaldo set sail on the USS Henderson, a transport ship. He arrived at Pearl Harbor on November 26, where he was assigned as an apprentice seaman to the USS Indianapolis (CA-35), the flagship of the 5th Fleet. Interviews with Indy survivors tell of the awe they experienced upon first seeing the Indianapolis. We can imagine Patrick was taken with similar emotion when first approaching this prestigious ship. Since 1932, the Indianapolis had escorted President Roosevelt on three international tours. Now a bona fide war ship, it had just returned to Pearl Harbor after receiving its first battle star for action in New Guinea. In total, the Indianapolis received 10 battle stars and Patrick Castaldo was an active combatant for 9 of them. The Indianapolis’s main role was anti-aircraft defense of carriers, and bombardment of islands which served to soften defenses in support of amphibious landings. At this point in the war, the island-hopping campaigns were focused on the paths that led to Japan’s mainland.

Described as a prestigious ship, the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35) turned heads throughout her sixteen years as the flagship of the 5th Fleet.

Seaman 2nd Class Castaldo’s first mission on the Indy was in March of 1943 in the Battle of the Aleutian Islands. Go to Cranford86.org to see the list of all the battles in which Patrick and the USS Indianapolis were involved.

In June of 1944 Patrick moved up to the rank of Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class just in time for the Indy’s participation in the landings off the Mariana Islands in the Philippine Sea. Due to the disproportionate loss ratio inflicted upon Japanese aircraft by American pilots and anti-aircraft gunners, the aerial part of this battle was nicknamed the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”. Japan’s carrier force and air power were forever eliminated there. 410 Japanese planes were downed, many falling victim to the guns of the Indianapolis.

In July of 1944 the Indy played a role in the Invasion of Tinian; its capture would play an important role in ending the war. She then proceeded to Iwo Jima to participate in the battle which resulted in the Marine’s famous landing there in February 1945. After Iwo Jima became the first of the Japanese islands to fall, a landing of D-Day sized proportions was being planned for the island of Okinawa. Essentially, every Allied Naval warship was assembled around the second Japanese island to be targeted. The Japanese army’s ability to defend itself by conventional means had now all but been eliminated. At this point the use of suicide pilots was their last desperate tactic at defending their homeland. On March 31st, 1945 during the 7th day of the Indianapolis’s bombardment of Okinawa, she was struck by a Kamikaze plane delivering a 500-pound bomb. The plane pierced the bow, penetrating several decks and the bomb exploded in the dining area, killing 9 and injuring 29. Our Cranford 86 hero Patrick Castaldo was one of the wounded.

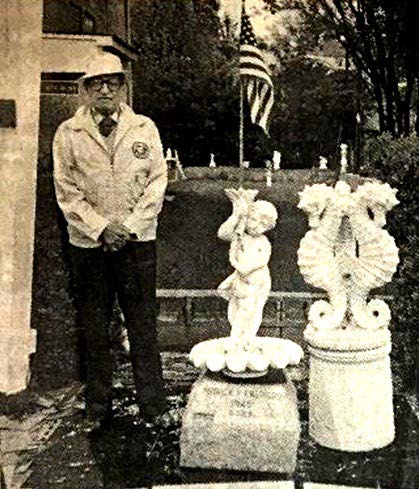

In Patricia Castaldo Hobbie’s Westfield backyard, a memorial to her uncle still stands, nearly 75 years after the Indianapolis tragedy.

Badly damaged, the Indianapolis limped for 6,000 miles to Pearl Harbor and then back to Mare Island for repairs. The crew was relocated to land accommodations or returned home for leave until repairs were completed. Patrick returned to his parents’ home in Bayonne to convalesce from his injuries.

Initially, it was estimated that the Indianapolis would spend four months in dry dock and then be sent back to the Philippines to prepare for the inevitable attack on mainland Japan. Repairs were mysteriously sped up with work continuing around the clock, completing the repairs in less than 60 days. It seemed that there was a plan for the Indy. Captain McVay was called to headquarters in San Francisco and given orders to ship out in 96 hours. Hundreds of telegrams went out across the country to recall the crew, most of whom were home on leave. Patrick, feeling better, received the call. He felt the need to join his brothers on the Indy and rushed cross country to reach his ship in time for its departure. It was July 17th, 1945.

Now with the rank of Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class, Patrick was a battle-seasoned member of the crew and was most likely known to most of the men on board. At 20 years old, he was older than most of the many new recruits who were 17 or 18. Captain McVay, while underway, opened his orders as instructed. The Indy was to pick up top-secret cargo at Hunter’s Point, just north of San Francisco, and then steam at full speed to Tinian in the Mariana Islands. The orders stated that every hour they saved on this trip would mean one less hour of war.

Patrick Castaldo, in his junior year at CHS, is pictured with the Mathematics Club, holding an enormous slide rule.

Ironically, just one year earlier, the crew of the Indy with Patrick Castaldo, was part of the attack that captured Tinian, and now this island was the site of the newest and largest air base in the world. It was from Tinian that the Enola Gay, a B-29 Superfortress bomber, would take off for Hiroshima carrying the “Little Boy” bomb that would end WWII. The Indy was to be under strict radio silence and would have no destroyer escort as was usually customary. There were two items that were loaded carefully at Hunter’s Point. One was a 5’ by 5’ by 15’ wooden shipping crate which was placed in a spot on deck that usually held a small observation seaplane. The other, which was stowed in a vacant officer’s quarters, was a 12” diameter black metal cylinder, about 2′ in height. Rumors of the containers’ contents were rampant throughout the ship and ranged from champagne for General McArthur’s victory party, to Marilyn Monroe’s underwear. Orders were given that, in case of an open sea emergency, these two items should be put in separate life rafts before any personnel attended to their own safety. What no one onboard knew was, that the large box held the components of the atom bomb “Little Boy” and the metal cylinder contained one half of the world’s supply of enriched uranium.

Shown in its pine packaging crate, “Little Boy” was the atom bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima. It was transported by the USS Indianapolis to the island of Tinian. This photo was taken on Tinian before the bomb was loaded onto the Enola Gay aircraft.

The Indy set a naval speed record to Pearl Harbor from San Francisco, 2,405 miles in 74.5 hours. Stopping there only for fuel, she immediately set out for Tinian. The dock at Tinian was lined with Marines at attention, holding automatic weapons and more military brass on it than anyone had ever seen. The crew knew that whatever they had on board; it was very important. The secret cargo was carefully unloaded. It was July 27th, 1945.

The Indy received orders immediately to set out for Leyte in the Philippines to prepare for the attack on the Japanese mainland. Captain McVay was assured that there was no Japanese submarine activity in the area. He requested a destroyer escort but was denied, told that all destroyers were assigned to rescue efforts of downed planes from the attacks on Japan. A destroyer had the electronic systems that gave protection from submarine attacks. A heavy cruiser had limited radar and no sonar. But, with no submarines reported, a destroyer was not deemed necessary for this straightforward journey

The Indianapolis was ordered to follow a zigzag course during the day and to use their discretion at night, depending on visibility. It was late on July 29th when Captain McVay retired from the bridge to his sleeping compartment. Zigzagging was terminated as the night was pitch black. Six miles ahead was something that reports said was not to be, a Japanese submarine. The war was almost over, and the sub’s commander, Lieutenant Hashimoto, had not yet had a “kill”, this was the moment that he had dreamed of. He submerged and was able to get unbelievably close to the Indianapolis. The submarine I-58 was armed with Kaiten torpedoes, 48-foot-long Kamikaze torpedoes manned with suicide pilots. However, Commander Hashimoto decided to spare the life of the pilots because he was so close, he felt he couldn’t miss. He fired six traditional torpedoes just three seconds apart. Each 1,210-pound torpedo had enough explosives to level a city block. Two of them hit the Indianapolis, one at midship that blew a hole 60 foot in diameter on the starboard side, destroying the power plant. The other hit the bow, breaking it completely off, which caused water to rush in as the ship was travelling at 20 MPH. It was 12:04 a.m. July 30th.

Patrick Castaldo’s home at sea for nearly 3 years, the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was a 610-foot heavy cruiser. Note the nine 8-inch guns that could hurl 335 lb. explosive shells seventeen miles. Her top speed of 37.6 mph was the reason she was selected for the top-secret delivery of the atom bomb “Little Boy”.

The Captain was awakened, and he took command. It was pitch black as all power had been lost. Even the emergency generators failed. The officers in charge could not even see each other as they tried to assess the damage. In order to stop the surging water, they needed to kill the engines, but no communication was possible with the engine rooms or to anywhere else on the ship. They weren’t sure if they had been rammed by a destroyer, hit a mine or were torpedoed, but they knew that the Indy was damaged badly, and it started to list in the water. Flames were raging throughout the ship but controlling them was impossible as all water pressure had been lost. It is believed that many men were killed instantly, and many others were trapped alive in the hull of the ship as compartments were sealed off to control the flooding. Despite all the damage, the radio operators were able to begin sending distress signals with the ship’s coordinates.

The situation was deteriorating quickly; the Indianapolis was sinking. Just eight minutes after the torpedo strike, Captain McVay ordered abandoned ship. With the ship already listing at 60 degrees and absolute chaos on board, an orderly abandon ship was not a possibility. The lifeboats could not be lowered, and only half of the life rafts could be taken from their mounts on the bulkheads. Most crew members were jumping over the side rail with a simple life vest or less. Many were badly burned or had broken limbs from the explosions. In the last minutes of the Indianapolis’s existence afloat it stood at 90 degrees to the water line. Soon it would find its final resting place nearly three and a half miles below the surface in the deepest ocean on earth. Nothing was left behind but scattered debris and 900 men bobbing in the water. It was only 12 minutes since the torpedoes had struck her.

As I write the details of these fateful moments, my thoughts are with our Cranford 86 member Patrick Castaldo. This horror was his reality. I find myself continuing to think, where was Perk at this moment?

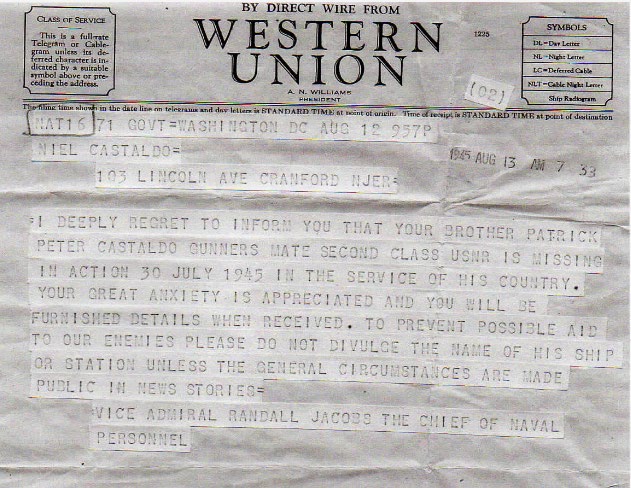

Th is is a copy of the telegram that uniformed sailors delivered to the door of 301 Lincoln Ave. on August 12, 1945.

More than 400 American war ships were sunk in WWII. Ships that sunk before the Indy were usually in a task group or at least with an escort ship. Some fatalities were expected when a ship went down, but survivors were usually quickly scooped from the water by a team of vessels that streamed in to assist. Due to the nature of the mission she had just completed, the Indianapolis was all alone, 300 miles from land. Her survivors’ only hope was that the distress signals were heard, and that help was on the way. Sadly, that was not the case.

Every sailor and officer in the water was covered by the thick fuel oil that was everywhere. There was limited water and food to sustain the hundreds of men who were clutching to flotation nets and life rafts, trying to just stay alive. Groups of survivors were being formed by officers. Captain McVay survived and was commanding one of the groups. By the end of day one, the injured and weak survivors were perishing. As the hours and then days passed, some sailors would start to drink saltwater, which resulted in organ shutdown and eventual death. Those suffering from severe dehydration and hypothermia were losing consciousness. Crew members began losing their minds and turning on each other. There were actual killings between men once considered brothers. Some men would just give up, releasing their life jacket to voluntarily sink below the surface in a drowning suicide. The life vests started becoming waterlogged and lost their buoyancy, they were only designed to work for 48 hours. Time was not on the survivor’s side.

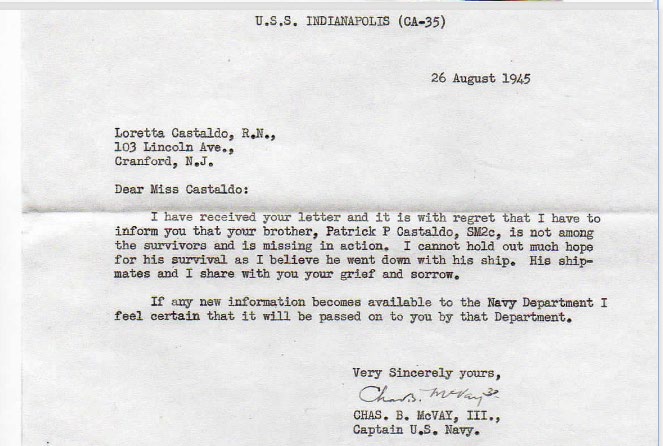

The hand-signed letter from Captain McVay, the commanding officer of the USS Indianapolis.

As the water started to clear of the oil slick, a new threat arose, sharks. There were hundreds and they were always present but would only feed at dusk and dawn. A lone survivor made the easiest target, but no one was safe from the random attacks. Hundreds of men were lost to the marauding fish, making this the largest recorded shark attack in history. This incident was made famous by Captain Quint’s soliloquy in the Steven Spielberg movie, Jaws.

A couple passing planes at high altitudes gave hope to the dwindling survivors, who by day three were estimated at half of the original number. With still no report of a missing ship, they were not noticed by the passing high-speed aircraft. Halfway through day five, the keen eye of Lt. Chuck Gwinn, flying a PV-1 Ventura bomber, noticed the oil slick. Lt. Gwinn was on a routine search and destroy mission looking for Japanese submarines and was shocked to see 20 or 30 floating men, waving and splashing to get his attention. Not knowing what he was seeing he came in for a closer look. Hundreds of bobbing men now became visible and he radioed for rescue vessels. From above, the schools of sharks were visible. Gwinn knew this was an emergency that needed immediate action, but help was still hours away. He dropped water and additional flotation devices but could do no more. What would follow would be the largest open sea rescue in American Naval history. Amazingly it wasn’t until the first survivors were brought onto a rescue ship that it was known that the sailors were from the USS Indianapolis. It was August 3rd, 1945.

On August 6th, the Enola Gay dropped the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Then three days later on August 9th, “Fat Man”, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered six days later.

In Patricia Castaldo Hobie’s Westfield backyard, a memorial to her uncle still stands, nearly 75 years after the Indianapolis tragedy.

On August 12th, 1945 the doorbell rang at 103 Lincoln Avenue. Six-year-old Patricia Castaldo rushed to answer it. Two uniformed sailors were standing on their porch, telegram in hand. They asked to speak to her parents. It was the family’s first notice that Perk’s ship had sunk and that he was lost at sea. A letter, hand signed by Captain McVay himself arrived later that month, confirming the same sad news. (See the telegram/letter at Cranford86.org) Patricia told us that the family held out hope even after this news. Patrick was an excellent swimmer and they thought that this fact may have saved his life. Sadly, that was not to be.

Loretta Castaldo, Dr. Castaldo’s wife, started writing to survivors to ask if anyone had memory of seeing Perk during the disaster. At first all the letters told the same story. No one remembered seeing him and that he must have been one of the 300 who never made it off the ship. Then, a letter came from a sailor who knew Patrick. He told of being with him in the water with a small group of men after the Indy sank. He said that Patrick was severely burned, was in terrible pain and had spiked a high temperature. The sailor went on to explain that he was hallucinating, as many of the men were, and had swam off because he thought he saw an airplane. He was never seen again.

Much controversy swirled as to who was to blame for the USS Indianapolis tragedy. The facts released by the Navy put the responsibility largely on Captain McVay and his decision to not use the zigzag technique to defend from submarine attack. He was court-martialed quickly for endangering his ship and crew. Some thought that he was made a scapegoat, in a plan to manage a situation that could interfere with public opinion of US military competence, following an unconventional act that ended a long deadly war. As a tormented man he committed suicide in 1968. At first, the public as well as the families of the crew members held Captain McVay responsible for their loss. Years passed and additional information about the myriad of errors and mistakes in judgement that led to the demise of the Indy came to light, causing feelings toward Captain McVay to turn around. Patricia Castaldo shared with us that their family’s feelings followed that same path.

As the eldest of nine children Dr. Neil Castaldo poses next to the memorial that he created in memory of his youngest brother. The seahorses not only represent the nature in which Patrick was lost, but also his love of his adventures at sea. Five of the nine Castaldo siblings served during WW2.

Finally, in 2001, Congressional hearings which were spurred by surviving crew members, resulted in a proclamation by President Clinton clearing Captain McVay’s name. The details, although interesting, are too lengthy to be included here. Go to Cranford86.org for links to many YouTube clips to hear the entire story. Much of the facts used to write Patrick Castaldo’s memoir were taken from In Harm’s Way. I also listened to the audio version several times. The entire heart-pounding drama is acted out with the appropriate passion to recreate each moment. It is based on survivor interviews, which ensures the accuracy of these incredible accounts.

Patricia said her uncle sincerely loved the USS Indianapolis, Captain McVay and all the crew, whom he considered brothers. She told us that Perk’s plan after leaving the Navy was to continue his education and become a dentist. His brother Dr. Castaldo served Cranford for 50 years as a physician, he had a monument created that depicted a sea horse with his little brother’s name engraved on it. Patricia still has a monument in her Westfield backyard. A monument honoring him also stands in his native town of Bayonne, NJ.

Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class Patrick P. Castaldo and the USS Indianapolis fought many battles together, and they both played such an important role in the victory of WWII. Patrick was an American patriot, one of our Cranford 86, and has earned our undying gratitude.

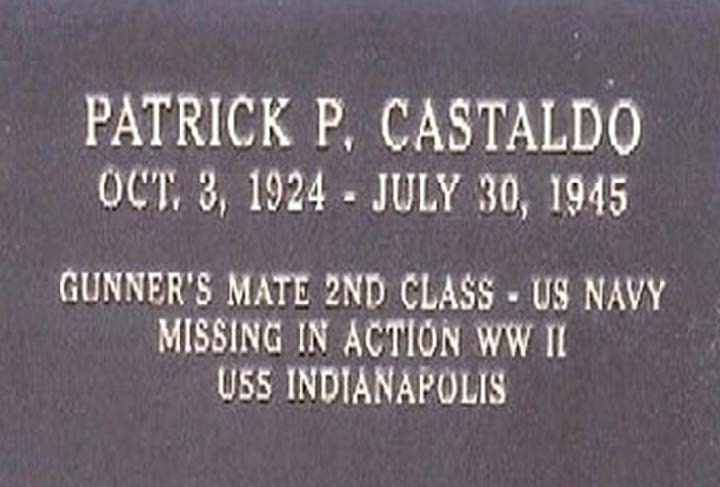

The plaque that memorializes Patrick, located in his native city of Bayonne, N.J.

USS Indianapolis: Largest Shark Attack in US History

USS Indianapolis Survivor Interview – Survivor tells of sailors experiencing hallucinations as they struggled in the water to survive.

Jaws (1975) – The Indianapolis Speech Scene – Indianapolis survivor, Captain Quint, describes surviving the shark attacks.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9S41Kplsbs

Missing The USS Indianapolis – Sea Tales A&E

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbzR2gZqUsc

USS Indianapolis Survivor Interview with Adolfo Celaya

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x3lL9ZVayHQ

94-year-old Survivor of the USS Indianapolis Sinking – Edgar Harrell tells his story.