By Al Shipley, City Historian and Rahway Library Research Consultant

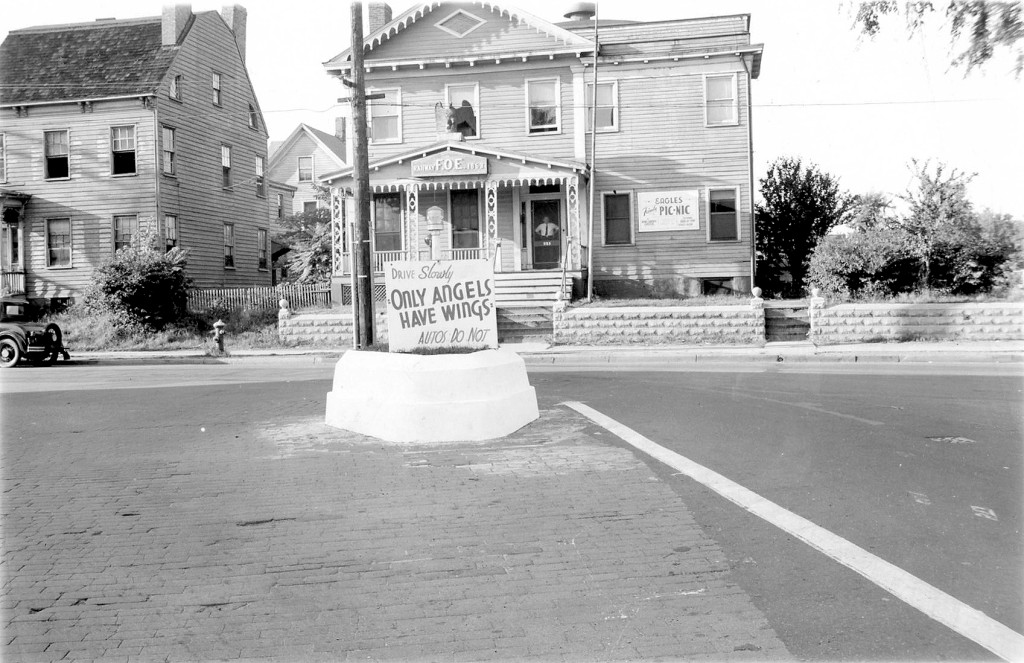

The Roaring 20s might have been coming to an end, but the automobiles of the period showed no signs of slowing down. Throughout the 1920s, 30s, and even into the 40s, serious and often times fatal accidents were occurring weekly on the streets of Rahway. Speeding and careless driving were attributed to be the main causes with poor street lighting and lack of traffic lights being contributing factors. Hundreds of summonses were issued at intersections along St. Georges Avenue, Hazelwood, Elizabeth, Grand, Milton, New Brunswick, and Lincoln Highway at the railroad overpass. As dangerous as these roads were, however, none were as hazardous as the quarter mile stretch of Route 25 between Grand Avenue and Lawrence Street.

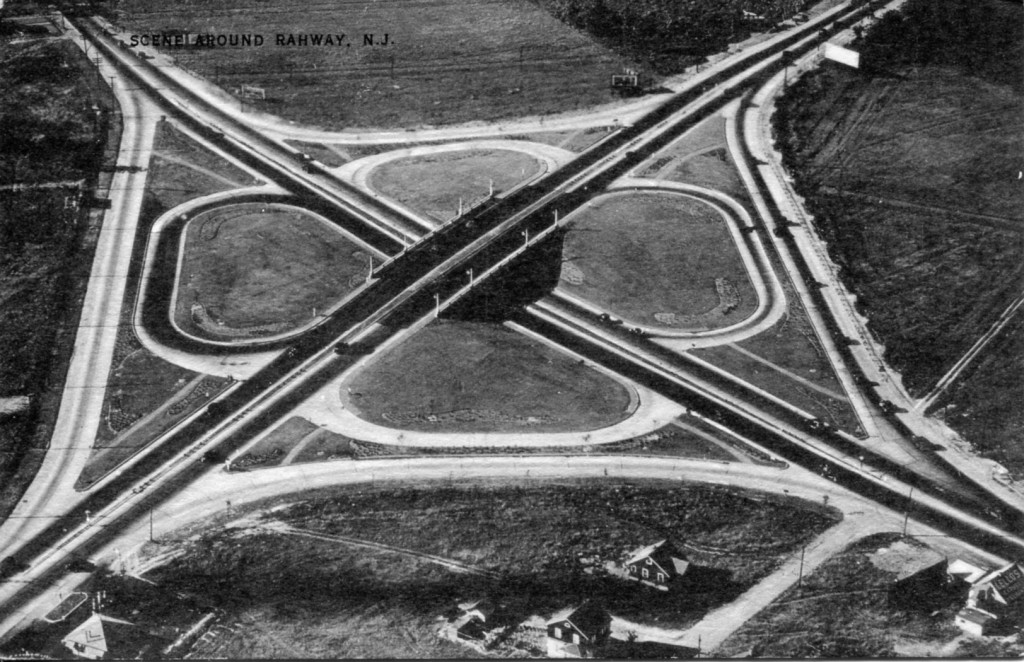

It’s hard to imagine a time when the road presently designated US 1&9 ended at the Linden/Rahway line at the railroad crossing and nothing but a grassy meadow stretched through the eastern section of Rahway to the river. In the early 1920s, the State Highway Commission began developing plans for a highway that would connect Jersey City and Newark with Trenton. In Rahway, this meant constructing a roadway through the meadow from Linden to Woodbridge. The plans also called for a bridge to cross over the river and Hazelwood Avenue.

On August 20, 1929, the new highway, designated Route 25, opened with high expectations. Travelling north, a motorist now had direct access to the Holland Tunnel. Heading south, one could proceed to Trenton via New Brunswick or switch to the shore route at the ingenious, ultra-modern cloverleaf junction in Woodbridge. Without a turn in the entire route, and covering a distance of more than fifty miles, the new, expressway was expected to make travel easier, faster, and less congested. With so much promise, few could have imagined that before the end of the first year, Route 25 would claim nineteen lives in accidents in Rahway and the nearby vicinity.

The unusually high number of accidents so soon after the opening did raise the concerns of local officials, but it was two horrific incidents at the intersection of Lawrence Street that would prompt them to take action. Late in the evening of May 10, 1930, a Public Service bus carrying thirty members of Company L, 114th Infantry, New Jersey National Guard, collided head-on with a sedan, killing three of the four persons in the car and injuring a dozen soldiers. According to police reports, the bus, which was returning from Newark, attempted to make a left turn onto Lawrence and collided with the northbound auto. The crash was so severe, the engine was ripped completely out of the sedan and the bus was sent careening across the road where it flipped over, but somehow miraculously righted itself. Two months later, on Sunday night, July 27, William McKinley Brown was killed while crossing Lawrence Street by a hit-and-run driver. At 31 years old, Brown was one of the most active young African-American political leaders in the city and had recently been appointed a constable. A witness told police the auto that hit him was travelling at a speed of 60 to 70 miles per hour. Unbelievably, the accident that took Brown’s life was the third at the dangerous intersection within an hour.

The Lawrence Street intersection was especially dangerous for reasons that should have been obvious. Entering Rahway in the north bound lanes, a vehicle would gain speed as it came down the steep grade of the bridge towards the dimly lighted intersection. Stop signs on Lawrence were the only traffic signals and although visible during the daytime, by the cover of night they could hardly be seen. This dangerous mix was made more harrowing with the fact that left hand turns onto and off the highway were legal thus creating a recipe for disaster.

By the end of July, the City Council established a committee to meet with the Highway Commission with recommendations to alleviate the hazardous situation. Suggestions from the committee included the installation of traffic lights and flood lights at the Grand Avenue and Milton Avenue intersections, the construction of a bridge at Lawrence Street that would go above and across the highway, and the elimination of all left turns. Not all of the requests were ever adopted and the ones that were faced many challenges before they were implemented. Which intersections really needed traffic lights (the state contended that too many lights would impede the flow of traffic), how would the lights be actuated, and who would pay for the improvements, were all questions that were deliberated. Traffic lights eventually were installed and left turns eliminated, but a bridge over the highway never became a reality. In fact, over seventy years would pass before Route 1&9 was elevated to cross over Lawrence Street.

One final accident of note that took place on Route 25 involved Elsie the Cow, symbol of the Bordon Dairy Company. Just after midnight on October 29, 1940, Elsie and her calf, Beulah, were being transported south when the truck they were in reached the Lawrence Street intersection and stopped for a red light. Behind them was a truck hauling ten tons of potatoes, cauliflower, and other vegetables. As the produce truck neared the light, its brakes failed. A solid rear end collision was only avoided when the driver steered his truck to the right, sideswiping and sheering off the side of the truck carrying Elsie. The produce truck, then out of control, leaped over the curbing, grazed a large pole, and turned over on its side. No one in either vehicle was seriously injured and because two bales of straw were at the rear of the truck where the initial impact was made, both Elsie and Beulah escaped injury.

(above) Traffic heading south on Route 25 is backed up at the Lawrence Street intersection in this early 1950’s photo.