Lieutenant Charles Albury Jr.

Meet Lieutenant Charles Albury Jr. World War 2 Glider Aviator, One of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney with Jim D’Arcy Past commander VFW post 335 and Lt. Col. Steven Glazer (Ret.).

A Waco glider

with a howitzer 75 mm spi ral cannon on

When I started the campaign to identify the faces and stories of the 86 men’s names engraved in bronze at our Memorial Park, I was much less educated about the history of American wars and the brave men and women that dedicated their lives to fight in them. Now with a year and 12 stories and several hundred hours of computer research under my belt, I consider myself an amateur historian. What has amazed me is the important role that many Cranford citizens have taken in some of the largest and most important military undertakings in our nation’s history. The grandeur of military actions and the planning that takes place months and years in advance of a mission is the segment that amazes me the most. Mostly all of the grand plans are considered classified and held as top secret. The individuals that will carry out the plans of attack, mostly know little or nothing about the encounter that they are about to play a major role in. The story of this month’s Cranford 86 Hometown Hero Lt. Charles Albury Jr. is just one such case in point.

Charles was born in Cranford on February 11, 1921 living first at 202 North Ave. East before soon moving to the home he grew up in at 113 Eastman Street. He attended Grant School and Roosevelt School and graduated from Cranford High School in the class of 1938, the first graduating class of the new and current high school. He was member of The Episcopal Church boys’ choir and an avid Boy Scout under Scout Leader Mr. Ireland. His hobbies were tennis and reading. He attended Hobart College, an all-boys school, in Geneva, NY, receiving his B.A. degree in 1942, with plans to become a teacher of history or perhaps English.

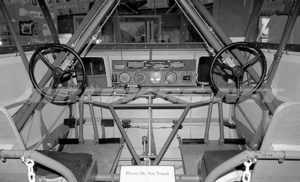

The simple cockpit of a WW2 glider

With America being fully engulfed in the world war in 1942, Charles answered his country’s call to duty. He volunteered for the Army in September of 1942, and completed infantry training at Ft. Benning, Georgia in April of 1943. He married his college sweetheart, Margaret Needham just days after. Miss Needham attended William Smith College, the all-girl sister school of Hobart.

In August of 1944 he was sent to England and soon to Holland where he saw action for the first time. With glider activity in World War 2 increasing, the demand for glider pilots was high. Charles volunteered for this very risky and exciting segment of military aviation. What Charles and the other volunteers didn’t know was that there was about to be an upcoming mission requiring a need for thousands of glider pilots during an invasion the likes of which had never been seen.

The march to Berlin was well underway, with successes at Normandy, The Hurtgen Forest and The Battle of the Bulge. However, the driving armies had reached a huge geographical obstacle, the Rhine River. It stood like a wall between thousands of Allied warriors in France and the Nazi headquarters in Germany’s capital, Berlin. The plan was to fly over this river wall.

Unlike the invasion on the beaches of Normandy which was supported by hundreds of offshore vessel and thousands of amphibious landing crafts, this invasion was to be accomplished with hundreds of aircraft, thousands of paratroopers and over 1500 gliders needing 2 pilots each. This need for more than 3000 pilots required the screening of nearly 4000 candidates; Lt. Charles Albury was one of those candidates.

Gliders and C-47 transports prepare for Operation Plunder.

The history of glider use in WW2 is interesting to me. I think it’s worth a minute to share the basic idea. Glider technology actually was started by the Germans in 1940; the Americans took the idea and improved on it. During the war in total 14,612 gliders were built and used, ranging in size from 8, 15, 30 and the largest a 45-seater. Along with troops, they could also carry jeeps and light artillery. Mostly manufactured by The Waco Aircraft Company, many however, were made by Ford Motor Co., Cessna Aircraft Co. as well as a furniture company, a piano manufacturer and oddly enough, a coffin manufacturer. The later manufacturer was the source of one of the more colorful nicknames of the gliders, “Flying Coffins”. Glider pilots wore a unique set of wings on their uniform similar to traditional aviator’s wings, except on the center of the wings was a “G”, for glider, the pilots claimed it stood for guts.

The gliders were pulled to the air by C-46 or C-47 transport planes and after release, the defenseless glider would fly silently through the night air into enemy territory. They would set down on fields hopefully undetected. Unlike paratrooper jumps that would drop a military unit scattered across a large area without any armaments, a glider could land in a specific area allowing a unit to quickly organize and set out on their mission with jeeps, ammunition and light artillery. After landing, the gliders were left behind never to be used again, the pilots would then became part of the military unit, taking part in the mission until reaching a rallying point, where they were transported back. With the end of WW2 being only two months away, this would be the last mass use of gliders in modern warfare. Gliders while being an effective militarily tool, were extremely dangerous and accounted for many casualties from crash landings often in the dark of night. The insertion of helicopters in The Korean War made the perilous gliders fortunately obsolete.

As fate would have it, our Hometown hero experienced the danger of glider warfare first hand. On December 12, 1944 at the age of 23, while training in Newbury, England, Charles volunteered for a test flight in a glider which for reasons unknown, crashed killing all on board. He was buried with full military honors at Cambridge American Cemetery in England. In 1948 his body was returned to American soil, he is now buried near Phelps NY.

On March 24th 1945 his classmates went on to be part of Operation Plunder, the largest single day airborne drop in history. Several hundred aircraft carrying 16,000 paratroopers and 1050 troop-carrier C-46 and C-47s towing 1350 gliders moved 7,220 personnel and munitions to the east side of the Rhine River in a successful mission. This was their last hurdle to crush the already damaged 3rd Reich. Hitler, seeing the end of his rampage was nearing, took his own life on April 30, 1944. A week later on May 7th, General Eisenhower accepted the unconditional surrender of the German Army from German Col. General Alfred Jodi in Reims, France. The war was over.

(above) Cambridge American Cemetery, England

A side note of interest was mentioned in a handwritten biography of Albury that is on file in the Cranford Historic Society’s archives. The Albury family migrated from Newbury, England to the Bahamas in 1740. To their knowledge no family member had ever returned to their English hometown. Ironically Newbury was the site of the crash taking his life.

Charles Albury’s wife Margaret gave birth to a baby girl on February 5, 1945. Born almost two months after her father’s death, her name was Margaret Charles Albury. Besides his wife and baby, who moved to Phelps, NY, Lt. Albury left a father Charles Albury Sr., his mother Mabelle, an older sister Betty and a younger brother Ronald Graham Albury, who was a junior in Cranford High School at the time. Ronald later became an Episcopal Rector at The Church of The Holy Cross in N. Plainfield.

Lieutenant Charles Albury Jr. was a great American and one of our Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes.

Waco CG-4A Glider built by Ford Motor Co.