Local African-American Woman was a Spy for George Washington

Submitted by Al Shipley, City Historian an Rahway Library Research Consultant

An article from the archives of the New York Times dated 1857 records the death of an elderly Black woman, known to Rahway’s “Bricktown” residents as Aunt Phillis, who perished in a house fire while she slept. Back in those early days, newspaper obits were rare and only written for very well-known members of the community or for those who had achieved prominence in a given field. The death of a woman, an average citizen, would have gone unrecorded if not for a number of curious items that were found in the ashes of what was left of her home. Sifting through the debris, authorities found papers and a small box that indicated she was a spy during the Revolutionary War and that she served under the direction of General George Washington.

It was a common practice for both American and British Armies to use spies and spy teams to go behind enemy lines to secure information. General Washington himself assembled a number of spy rings that became an important and organized intelligence operation. These secret agents might include merchants, tailors, farmers, slaves, and young women. They not only gathered clues concerning the imminent plans of the enemy forces, but also spread misinformation to confuse them. They worked under secret identities, used secret codes, and were familiar with the locations of secret “dead drops,” spots where information could be deposited. This was dangerous and risky work. Death by hanging or firing squad was the punishment for those who were not clever enough or lucky enough to conceal their stealth. Washington became so adept at using his spy teams that one defeated British intelligence officer was recorded as having said, “Washington did not really outfight the British. He simply out-spied us.”

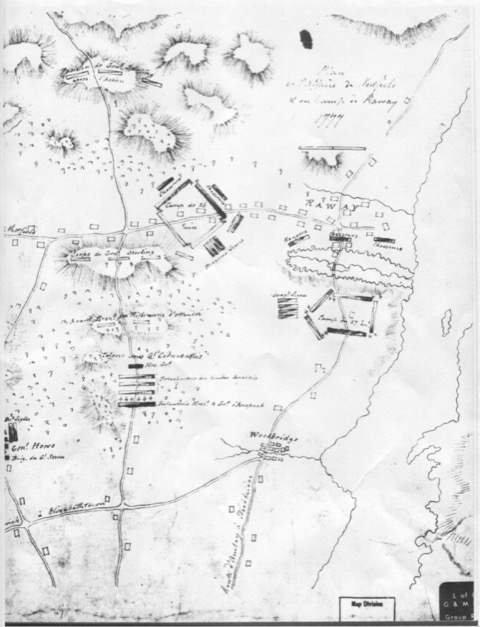

Rahway’s location during the war years made it a strategically important and dangerous area. Woodbridge, Perth Amboy, and Staten Island were British strongholds which put Rahway and neighboring rebel towns in precarious positions. Following the Battles of Trenton (December, 1776) and Princeton (January, 1777) Washington directed his officers to drive the Redcoats out of Central Jersey. The need for advance knowledge of enemy plans became essential which created the perfect training grounds for a young woman to hone her spying skills. A young woman like Aunt Phillis, might be able to more easily infiltrate enemy lines under the guise of doing her routine chores. Moving around openly in an enemy camp could enable her to get close enough to overhear important conversations without arousing suspicion. The full extent of her work as a spy is not known and it was not until some 80 years later that some light was shed on her past.

Late on a Friday night in 1857, a home located on the eastern end of Rahway on the banks of the Rahway River, a section of the town where bricks were made, went up in flames. Before the volunteer firemen could arrive, the structure was entirely destroyed. The body of Aunt Phillis was found the next morning and removed in the custody of the County Coroner. It was while moving through the remains that items were found linking her to Washington and her service during the war. Charred papers indicated that, though only in her teens, she contributed considerable service to the American troops. The papers outlined how Aunt Phillis spent the winter of 1777-78 with Federal troops camped at Bound Brook and might have been in the special service of Washington who at that time was carefully monitoring the events in that region. Along with the papers, a gold inlaid snuff-box was found in the rubble giving more credence to the Aunt Phillis story. The box was a presentation gift to her given by Governor William Livingston “in recognition of her services.” Livingston, who lived in Elizabethtown, was a signer of the United States Constitution and New Jersey’s first governor.

As is the case with the spying exploits of Aunt Phillis, nothing is known about her life after the war, but the relics found on the morning after her death, reveal the existence of an American patriot who was lost in time.