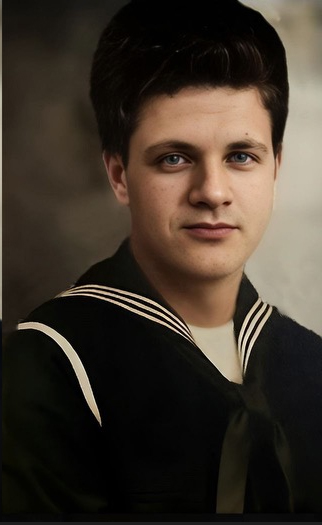

Meet Seaman 1st Class Edward Mandoni, U.S. Navy Armed Guard Defending an American Liberty Ship, WWII

By Don Sweeney and Janet Cymbaluk Ashnault, Research by Vic Bary and Don Sweeney, Military guidance by Vic Bary

Month after month, our team continues with its efforts to tell the stories and reveal the visual identities, of the 86 brave men whose names appear on the bronze plaques at Cranford’s Memorial Park. Recently, a former Cranford resident, Donna Blackburn, drew our attention to the name Edward Mandoni. Donna is a follower of Bernie Wagenblast’s Cranford Radio podcast. Shortly before Memorial Day, 2022, we were featured on Bernie’s show to talk about the Cranford 86 project. Listening to the podcast, Donna realized that her uncle, Edward, brother of her father Donald Mandoni, was one of the Cranford 86. She asked us if we had any information about Edward Mandoni that we could share with her. At that time, all that we had was a short Cranford Citizen and Chronicle article about her uncle’s death on a Merchant Marine cargo ship. We always look forward to a call from a family member that helps us fill in gaps of information, but in this case, the relative had even less knowledge than we did. We shared the article with Donna, and she gave us some family names that we could add to our research inquiries. Our policy is to begin the research and writing process of a Cranford 86 serviceman, only when we have obtained his portrait, preferably in uniform. Donna and I promised each other that we would reach out if a photo of her uncle was found.

In 2023, we were researching Yankee baseball player-turned soldier, Cecil Spittler. In the Spittler family archives we found a page from the May 10th 1945 edition of the Cranford Citizen and Chronicle. Published three days after Germany surrendered, the page featured the photos of Cecil Spittler and 23 other men, and was titled “Liberation of Europe Cost the Lives of These Cranford Men”. We noticed that among these photos there was a portrait of a handsome sailor wearing a serious and somewhat sad expression. The photo was grainy, but recognizable, and its caption confirmed that it was of Edward Mandoni. We were very excited with our find and called Donna Blackburn to share the news. We told her that the research process could begin and we could possibly feature her uncle’s story at the 2024 Memorial Day morning ceremony. Donna was more than happy to help our mission progress by becoming the sponsor of her uncle’s banner.

Edward’s Life in Cranford

Edward’s parents, Benjamin, a construction worker, and Bertha, showed up in Cranford on the 1930 census, living on Garfield Street. With them were the first five of what would eventually become a family of nine children. Edward, born on September 21st, 1925, was four and a half in 1930. If you are not familiar with Garfield Street in Cranford, there’s a reason for that! Garfield was located off of Centennial Avenue, southeast of Hayes Street. Construction of the Garden State Parkway through Cranford in the late 1940’s, eliminated Garfield, Harrison, Cleveland, Roosevelt and McKinley streets. Of that neighborhood of streets named for U.S. presidents, Hayes, Grant and Buchanan still remain. The Mandoni family attended St. Michael Church in Cranford, where most likely, they filled an entire pew.

This large family, living in Cranford in the midst of the Great Depression, with World War II looming, was struck a tragic blow when Bertha died in 1941 at the age of 47. Not all of the children were able to finish their education, as we surmise that they needed to leave school to help to support their father and siblings. We know that Edward attended Lincoln School and he should have graduated Cranford High School in 1943. We saw him in preceding CHS yearbooks, in the Aviation Club and on the Cross Country Team. Edward’s Draft Registration Card, dated 1943 showed him hard at work for the Lewis Asphalt Engineering Corporation on Central Avenue in Clark. There is no mention of him in the Golden C as a graduating member of the Cranford High School Class of 1943. On November 29th of that year 18-year-old Edward left Cranford to begin his training for service in the U.S. Navy. Destined for a hazardous and relatively unknown duty, Edward’s willingness to serve our country during a world war already solidified him as a member of what would one day be known as our Greatest Generation.

MOS, U.S. Navy Armed Guard

Donna Blackburn was under the impression that her Uncle Edward was a Merchant Marine like her father Donald. As we quickly learned, this was not the case. Young Edward attended military training in Rhode Island and at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City. His training in New York prepared the Seaman Second Class for duty as a United States Navy Armed Guard, providing onboard defense of Merchant Marine cargo ships. Edward Mandoni is the first Cranford 86 serviceman that we know of who had this type of duty. The Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) of so many of our heroes has called our attention to a variety of military roles, engineering wonders and important historical engagements. As well as making our stories so interesting, sharing the varied experiences of our Cranford 86 has greatly broadened our knowledge of our country’s history. In telling Edward’s story, we knew that we were about to learn much about a military assignment which we had not touched upon until now.

Our country fought WWII on many fronts, one of course being the world’s oceans. The ability to successfully transport immense quantities and varieties of cargo overseas, including fuel and ammunition, was an absolute requirement in order to achieve victory. For the island nation of Great Britain, which was the last standing European power, safe arrival of basic supplies as well as military hardware was especially critical. If not for the force created by the American-made Liberty Ship, the civilian United States Merchant Navy and the U.S. Navy Armed Guard, our WWII history books would probably be telling us a different story.

Even before our involvement in WWII, U.S. merchant ships, traveling all throughout the world, suffered unprovoked enemy attacks. The Neutrality Act, created by our government to prevent U.S. involvement in foreign war, prevented us from arming U.S. merchant ships. In October of 1941, after a lethal stretch of U-boat attacks on both U.S. Navy and merchant ships, that section of the act was repealed by Congress. Later that year, five days before the Pearl Harbor attack, the first Navy Armed Guard crew of seven, joined over 30 civilian Merchant Marines on the SS Dunboyne. As part of a convoy, their destination was the Soviet Union’s Arctic port of Murmansk, a run which became infamous to the merchant ship crews. Not only was it treacherous in terms of enemy fire, but it took the ships through the worst weather in the world.

With the U.S. Navy found short of all things needed to fight a modern war, roll out of the Armed Guard suffered a rocky start, and early on, many ships went out ill-equipped in terms of armament and quantity of crew. Some vessels, armed with only a few machine guns, had their crews paint and position telephone poles to resemble the barrels of larger weapons. Losses of both ships and men were heavy during this time. In addition, members of the Armed Guard felt orphaned by the Navy. Stationed on slow-moving rust-streaked freighters, the sailors needed to coexist with civilian seamen who were not as disciplined and had much higher salaries than their Navy shipmates. It was said that the ship’s baker made more money than any member of the Armed Guard. At this point in time, the protection of merchant ships may have been the least desirable job in the Navy.

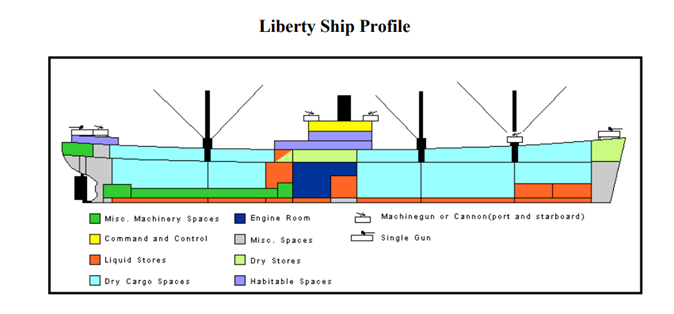

By the time Seaman 2c Edward Mandoni was assigned to his ship, the war had worsened, but the Armed Guard was in better shape to fend off the enemy. The Navy had responded to the shortage of staff with accelerated training programs and the merchant ships were better equipped defense-wise. The standard armament for ships traversing combat zones consisted of a lethal 5 inch dual purpose stern gun, a 3 inch anti-aircraft gun, and eight 20 mm machine guns mounted at strategic locations. Armed Guard crew consisted of one or more officers and twenty-four gunners, plus three communications men for a total of 28. When under attack, the Merchant Marines worked beside the guardsmen, passing heavy shells or manning machine guns if needed.

America’s Manufacturing Might and the Production of the Liberty Ship

WWII has been said by historians to have been a war of production might. A prime example of this was the manufacturing feat which created thousands of “Liberty Ships”. Prior to December 7th, 1941, when British cargo ships were getting torpedoed at an astonishing rate, Britain made it clear that their ability to supply themselves and their war efforts was in serious jeopardy. They made a desperate plea to the U.S. for assistance in the rapid production of cargo ships. Using the British-designed Empire Liberty Ship as a model, America responded with the production of their own version of that vessel. Each American-made Liberty Ship could carry an incredible 10,000 gross tons of freight, translating to 2840 Jeeps or 440 Sherman Tanks. It could even load and unload itself in remote areas with its three heavy duty cranes. The story of the manufacturing of the Liberty Ship is incredibly interesting and it would be America’s first step to becoming the world’s superpower of military might. See the links to the Liberty Ship story in the online version of this story at Cranford86.org.

American businessman Henry Kaiser had just completed construction of the Hoover Dam. Kaiser, selected out of all other bidders, was awarded lucrative military contracts to manufacture Liberty Ships. The ten year, Depression-era project which dammed the mighty Colorado River and built the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant, was referred to as the “Eighth Wonder of the World” and it made Kaiser a national hero. He planned to create ships with the methodology that had been used by Henry Ford and other Detroit automobile companies since the turn of the century. Critics claimed that Kaiser had no experience building ships and to that he responded, that before his success with the Hoover Dam, he had never built a dam.

Kaiser applied mass production techniques, including prefabrication, in the construction of the Liberty Ships. Replacing riveting with welding reduced the number of construction team members and cut their training time in half. Ships that previously took several months to build were being produced in an average of eighteen days. During peak production, American shipyards were turning out three Liberty Ships every two days. Some historians claim that Japan’s attention to America’s pre-war ability to build war hardware, made them attack the U.S. much earlier than originally planned. Japanese fears were warranted, for after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. manufacturing of war hardware, led by Henry Kaiser would mass produce aircraft carriers, submarines, and landing crafts in the same manner as the Liberty Ships, changing the course of the world war. Pre-war, the United States collection of submarines, aircraft carriers and landing crafts numbered 783, post war it was an astonishing 6,998.

Onboard the SS Dan Beard

After a visit home to Cranford in May of 1944, Edward Mandoni was serving on the SS Dan Beard, which was one of the 2,710 American-made Liberty Ships. The ship was named after Daniel C. Beard, an American illustrator, author and youth leader who was a founding pioneer of the Boy Scouts of America. On the Dan Beard, its guns proved effective against attacking aircraft and any U-Boats that were on the surface of the water, however it was defenseless against torpedoes fired from submerged submarines. For this reason, in open water situations, merchant ships usually traveled within large convoys, protected by speedy, nimble destroyers. The Dan Beard was awarded a battle star for its participation in the Normandy Invasion, arriving with its cargo two days after D-Day. After being relieved of service at Omaha Beach the ship headed for Ireland.

An official timetable of events describes what happened next.

“On December 10th, 1944, the SS Dan Beard left Barry, Wales at 02.00 hours, travelling unescorted because the Admiralty had reported the Irish Sea was clear of U-boats and was ordered to sail alone. At 13:55 in rough seas a torpedo struck at the #3 hold on the port side, then a second struck the stern, rised the ship out of the water, blew the rudder and broke the propeller. The upward motion of the ship caused her to break in two at the hold 3 seam, where a plate had been welded over a construction crack repair that was made a year earlier. The aft part sank immediately, and the forepart drifted ashore and was wrecked, settling into a cove where her mast is still visible at low tide to this day. Miraculously, a successful abandon ship was achieved into four lifeboats. One lifeboat was swamped and another capsized in the 30 foot seas. Sixteen men reached Pwll-Deri Bay, Porthgain, South Wales in one lifeboat and another made landfall as well. A coastal craft picked up 13 others adrift on a life raft, possibly survivors from the capsized lifeboats. One of the survivors rescued died enroute to the hospital ship. Three officers, fourteen merchant mariners and twelve armed guards were lost”.

The ship broke apart on a seam that had been previously patched. This was a common problem for the mass produced, prefabricated Liberty Ships. No SOS signal was sent from the vessel and reports state that its communication antennas were inoperable. Perhaps Dan Beard needed repairs and for that reason was headed to the shipyards in Belfast, Northern Ireland, birthplace of the Titanic.

Thank You Seaman Mandoni

Edward Mandoni had sent letters home during his service describing visits to London and other highlights of life in the Navy. His letter dated December 9th, 1944, indicated that he would be “home soon”. But it was in this torpedo attack on December 10th that Edward Mandoni, age 19, lost his life while serving our country, his body was never found. Classified as lost at sea, a monument that bears his name is meticulously maintained at Cambridge American Cemetery in Cambridge, England. Edward was survived by his father and 8 siblings. His brother Donald, at the time, was a Merchant Marine serving in New Guinea and brother Thomas was with the Army in Belgium. At some point, perhaps upon his death, Edward was promoted to Seaman First Class.

Serving in a world war, this Cranford teenager took on an extremely hazardous duty that was relatively unheard of, it lacked the pride one had when serving on a sleek warship and the job received little to no publicity. But, without Edward Mandoni and his fellow guardsmen these cargo ships, themselves valued in total at $22,500,000,000, would have been defenseless. The value of the cargo carried cannot be measured and the safe arrival of these ships to their destinations played an extremely critical part in the Allied victory. Seaman First Class Mandoni and the United States Navy Armed Guard have earned all of the respect and gratitude to which they are entitled, and we are very fortunate to have the opportunity to tell their story.