Meet PFC Daniel A. Hildebrandt,

One of Cranford’s Hometown Heroes

By Don Sweeney, Vic Bary and Janet Ashnault, Researched by Stu Rosenthal and Vic Bary

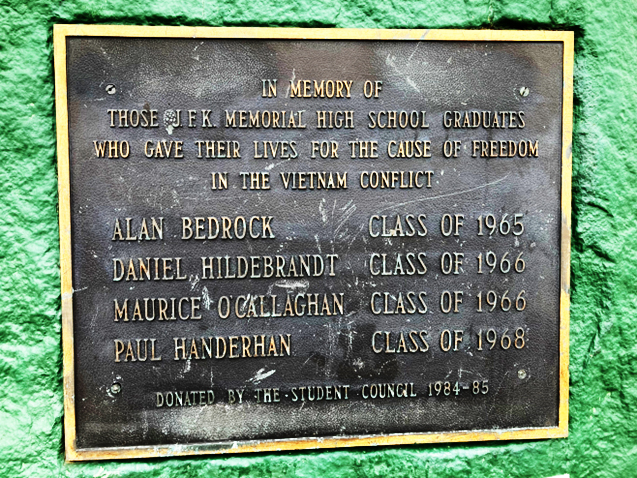

Memorial Day 2023 marks the sixth year in a row in which we will reintroduce to Cranford’s residents another set of their Hometown Heroes. I find myself thinking back to those who inspired us to embark upon this mission. First there was the late Bob Greco, who was a WWII veteran and member of Cranford VFW Post 335. On Memorial Day, Bob would read the names of the 57 Cranford men who perished in four short years in WWII, most of whom were his classmates at Cranford High School. At the time, Bob was one of the few who remained in Cranford who could still remember, not only the faces of these men, but how they each contributed to victory in Europe and the Pacific. It was then that we realized that, slowly and silently, the images of these heroic men were fading and they were starting to become “just names”. Also, there was Mike Sapara, a Vietnam veteran who carries a deep devotion to the memory of his classmates from Cranford. Mike wore metal tribute bracelets for Ray Ashnault, Joe Minnock and Danny Hildebrandt who all went to Vietnam before Mike did, but, unlike Mike, they did not come home. When Mike shared with us his thoughts about the Vietnam War and the friends that he lost, this was the spark that ignited the writing of the very first Cranford 86 story (rennamedia.com/cranford86/the-cranford86-project). The U.S. government lists the “address of record” as Cranford for both Ray Ashnault and Joe Minnock. Therefore, when they died, they became a part of Cranford’s history and were embraced as two of Cranford’s 86. Their stories were among the first written by the Cranford 86 project and their street banners fly proudly throughout town. We know their names and we can see their faces. Danny Hildebrandt spent the majority of his life here in Cranford, but at the age of fifteen he moved with his family ten miles away to Iselin, New Jersey. Even though young Danny lived out of town, he was able to keep the close ties that he had with many of his Cranford friends. The memory of Danny Hildebrandt, as a son of Cranford, still lives in the heart of Mike Sapara and so many from Cranford who knew him. Although Danny is one of those who “gave all” in Vietnam, because of his Iselin address, he is not specifically included in Cranford’s yearly Memorial Day observance. You will not see his name inscribed on the brass plaques at our Memorial Park in Cranford.

“What About Danny Hildebrandt?”

Danny Hildebrandt was born on February 21, 1948, to Margaret and Edward Hildebrandt. He lived with his parents and siblings, Edward Jr., Patty and Keith on Roger Norton Place in the Indian Village section of Cranford, ironically on a street named in honor of a WWII Cranford 86 Hometown Hero. Edward Sr. worked as an independent plumber and was later employed by Reynold’s Plumbing in town. The Hildebrandt’s life in Cranford was interrupted in the late 50’s when they sold their home in town and made an abrupt relocation to California for an employment opportunity. The California experiment didn’t pan out and the Hildebrandts found themselves back in Cranford again, this time at a smaller rental home on Woodlawn Avenue. They lived here for 3 years, until their move to Iselin in 1964.

Faithfully, every few months, Mike Sapara checks in with us to let us know how much our stories mean to him and to offer his well wishes to our team. Mike never ends a call without asking if our efforts to tell Danny Hildebrandt’s story had at all progressed. I always provide him with the same answer, sometimes in exasperation, and explain how the address of record is what defines the boundaries of our project and there wasn’t anything that could be done to change that. Mike was never deterred by my repeated explanation and he continued to close every one of his phone calls with that same question.

As our team continues to roll out our servicemen’s stories, we receive feedback, either in person or from our Facebook followers. Many times, our readers ask, “What about Danny Hildebrant?” A few years ago, while shopping in Pathmark, my wife Joanne’s friend, Carol Korner Riley, approached me. Carol said, “Don, I have been reading your stories about the Hometown Heroes, did you know about Danny Hildebrandt?” I went into my usual response, explaining about Danny’s address of record being in Iselin. Carol told me that she and Danny had been a couple and they were in love as two young people could have ever been. She said that they had plans to marry when he returned from Vietnam. The emotion that I heard in her voice was evident, and it caught me as well. Despite the address guidelines, I promised Carol that I would someday find a way to have Danny’s story told. Last year I heard that our friend Carol was having some serious health issues, I started thinking that if we were ever going to do Danny’s story, that we should do it now. With a month to go before Memorial Day, we already had the stories of three WWII infantrymen completed. Supported by Carol Riley’s willingness to share her memories, we decided that we had a small window of opportunity in which to research the details of Danny Hildebrandt’s life and tell the story that led to him serving our country in Vietnam in 1968.

Cranford 86 Researchers in Action

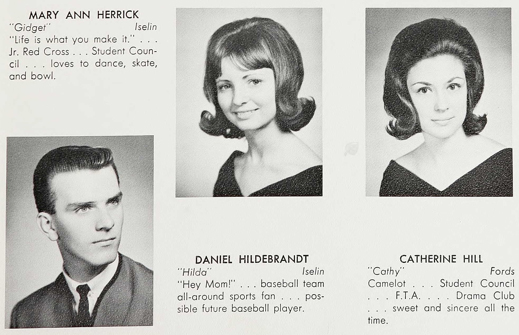

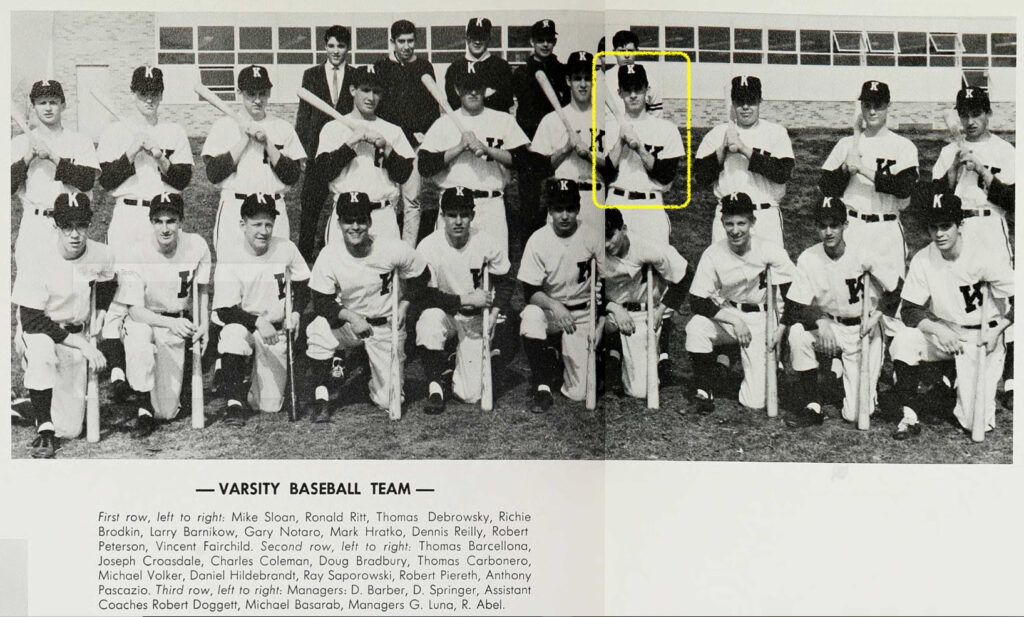

In a process that has now become like second nature to them, Cranford 86 researchers Stu Rosenthal and Vic Bary, swung into action. Stu immediately found several mentions in the Cranford Chronicle archives which gave us a glimpse into Danny’s early days. The “School News” column reported on Danny’s elementary school activities, drawing birds with his second grade class at Walnut Avenue School, his appointment to class president for the month and his entry in the Safety Poster contest which won a prize. The newspaper also referenced Danny’s membership in Cub Scout Pack 82 at the Community Methodist Church. Danny’s athleticism began to become evident as we found his name mentioned in a dozen baseball-related articles. After little league in Cranford, Danny advanced to the highly competitive Union County Baseball League where the write-ups were focused on his crucial contributions in big games. His contemporary on the ballfield was Cranford 86 member Ray Ashnault. In some instances, he and Ray were on opposing teams but on the Cranford All-Star team that played other towns, they were teammates. During Danny’s junior and senior years at JFK High School in Iselin, the Woodbridge local paper reported on his continued high level of performance in baseball.

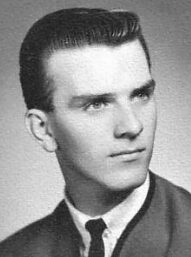

Never ceasing to amaze me with his investigative skills, Stu Rosenthal promptly sent me a phone number which he believed was that of Danny’s younger brother Keith, age sixty-five, living in Florida. The voice mail message indeed indicated that the number belonged to a “Keith”. I left my message, explaining our project and asking for a call back. Four days passed and I was starting to think that perhaps I had the wrong Keith. Or, maybe I did reach Keith Hildebrandt who was reluctant to reopen the book on the circumstances surrounding his brother. This is always a possibility in these encounters that we make, involving a life which has ended so sadly. Finally, on day five my phone rang, indicating a call from Florida. It was Keith Hildebrandt and we set a time for an interview that night. Keith explained that he was just seven years old when his family left Cranford, and nine when he lost his brother. We spoke for nearly an hour as he shared how devastated he was, to lose his older brother whom he idolized. During our talk, I experienced déjà vu, as this was the third time that I had interviewed the younger brother of one of Cranford’s Vietnam War heroes. John Ashnault and Todd Elichko, younger brothers of Ray Ashnault and Dean Elichko had shared with me similar poignant and precious memories from so many years ago. John, Todd and I are similar in age, and we have become good friends since the Cranford 86 mission brought us together. Keith explained that his brother was a natural born athlete which confirmed what we had read in the local newspapers. Danny was a mentor to his younger brother and taught him everything about sports. Keith said that he wanted to do everything just like his big brother, telling us that Danny excelled in football and track as well. Remembering the emotional interviews which I have conducted in the past, I listened more than I talked and learned about this special relationship between a ten year old and his twenty year old brother. The emotion was deep, and the memories had not faded a bit. Keith told us that he had fond memories of Carol Korner and was happy to hear of her contribution to his brother’s story. Keith’s mom would send him along on many “dates” with Danny and Carol, going sledding or ice skating, and Carol always made him feel welcome. Later, even after Danny’s death, Carol was their family’s hairdresser. Keith quickly set up a phone meeting with Carol, eager to reconnect after so many years. Keith’s fond memories of his brother summarized Danny Hildebrandt as a kind, funny person and a generally nice guy. In every interview that I conducted throughout the week, the stories were different, but those descriptions, “kind, funny and a nice guy” were repeated time and time again. In addition, whether I spoke to men or women about Danny, there were always comments about his incredible good looks.

I invited Carol to our home to talk with Joanne and me about the wonderful days when she and Danny Hildebrandt were a couple. They first met in the high school nurse’s office. Carol was just fifteen and Danny, who was fourteen, was sitting there with his leg in a cast, the result of an ice skating injury. They had a chance to chat casually and I imagine that the conversation was full of humor, something that is typical of Carol. As the school year progressed they started seeing each other, going to the movies and such, but their first kiss was a long time coming. One night, in a carful of kids, driven by their friend John O’Donnell, they were being dropped off at their respective homes, one by one, in order of convenience. As Danny worked his way from the back seat, he had to cross over Carol. Thinking that it was about time that they shared a kiss, Carol grabbed him and planted a big one on him. He sat back down and told John, “Drop me off with Carol, I’ll walk home”. From then on, they were going “steady”. The story that touched me the most was the one where she was in front of the Cranford Hotel waiting for Danny. She watched him approach in his stylish, well-fitting attire, typical of the 1960’s, skintight, green, beltless “continental pants”, with a white collared button down shirt and his short sleeves rolled up high. She remembered saying to herself as he approached, “I can’t believe that’s mine”. As Danny was about to start his junior year in high school, it was a sad day when he told her that their family was going to leave Cranford again, this time to buy a home in Iselin. Not to allow the miles between them to keep them apart, Carol remembers walking to Iselin regularly. The trip by foot would take a solid two hours and she walked it many times to watch Danny play baseball at Iselin’s Merrill Park. Danny would make the same trip to see her, by bicycle, until they reached driving age. Graduating high school one year ahead of Danny, Carol became a hairdresser at a beauty salon in Cranford. Danny worked at ShopRite in Avenel during high school and after graduation, took a job at Revlon, where his uncle was employed.

1967 – The Draft Escalates

The Vietnam War served as a backdrop to their lives during these times, and Walter Cronkite’s nightly news broadcasts kept the American population up-to-date on the fighting. United States involvement was escalating rapidly and the war that was at first predicted to be a short encounter for our armed forces, was quickly becoming a war that some thought was unwinnable. The sensitive political climate surrounding the civil rights movement, intertwined with anti-war protests made this period in our country’s history very complex. By 1967, the number of Americans in harm’s way in Vietnam was reaching 400,000, and President Johnson was pledging to send more and more American boys to the battlefield each month. Danny soon received a letter from the draft board calling him to service, bringing him and his family squarely into the center of these wild times. Carol would tell us of a verbal deal that was cut with Danny’s recruiter. If Danny was to “up his draft” he would be able to select his war time destination. Even though Danny agreed to the terms and entered service before his original date, his destination was not as he had selected, as the extreme demand for soldiers needed in Vietnam would not allow it. Mike Sapara explained to us that recruiters were salesmen of sorts and sometimes, to close a deal, they would offer special situations that they could not guarantee. From a remembrance left on the Vietnam veteran tribute site called The Virtual Wall, we were able to connect with Danny’s JFK High School classmate Matt Winkler. Matt told us about meeting Danny at Fort Knox in Kentucky where they spent eight weeks together. Their casual friendship was renewed and developed further there, even discovering that they held consecutive draft registration numbers. For their Advanced Individual Training, Matt stayed at Fort Knox for further education in radio school, while Danny attended Advanced Infantry Training at another base for his very dangerous Light Weapons Infantry MOS (11B10). Matt figured that with Danny’s strength and athletic ability, the Army determined that he’d be most valuable to them as an infantry soldier. Luckily, Matt was sent to Germany for the rest of his service.

Carol commented on how fast everything happened. “Danny reported for duty to Newark in August, and went immediately to Fort Dix, where he was sent by plane for basic training. He never returned until shortly before he shipped out to Vietnam in January”. She wondered how such a kind, funny and friendly person could be transformed into a hardened soldier in such a short amount of time. Seeing Danny before he left, made her doubt that he had been changed at all.

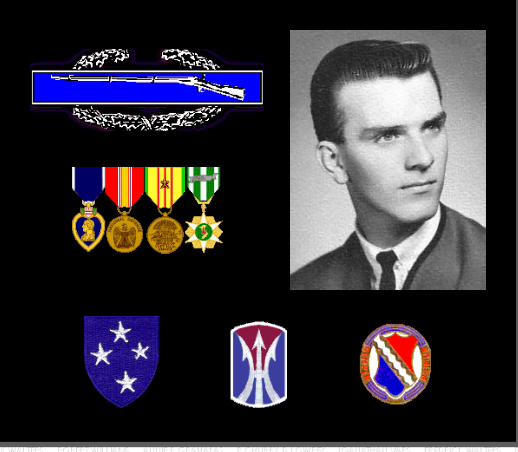

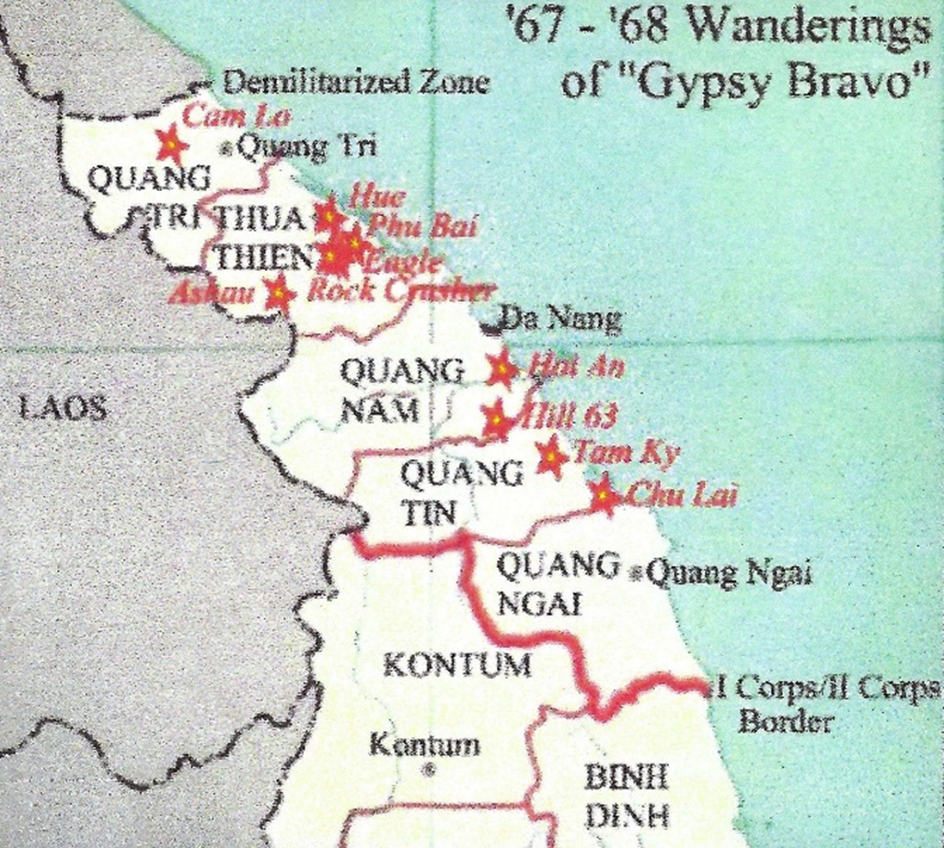

The Americal Division in the Quang Ngai Province

To help us write Danny’s story, we connected with many friends and family members, but none were able to provide us with any documents or photos from family archives. The 56 years that had passed left each of our contacts without a single personal artifact for a variety of reasons. We know that PFC Daniel Hildebrandt became a member of the infantry unit known as the Americal Division. Americal is a contraction of the name “American, New Caledonian Division” which references the South Pacific island on which the division originated in WWII. Americal was reactivated in September of 1967, to help combat the guerilla style warfare that the Viet Cong developed in their decades-long battle, defending their homeland against numerous occupiers The Viet Cong used expertly designed land mines and booby traps and had the ability to create underground shelters with elaborate tunneling. The U.S. military’s advanced air and ground machinery, which normally gave them modern war superiority, was rendered largely ineffective due to the covert tactics of the Viet Cong. We knew Danny served in Company A (175 soldiers), 3rd Battalion (700 soldiers), 1st Regiment (1,500 soldiers), 11th Brigade (4,500 soldiers) of the Americal Division (15,000 soldiers at full strength). He joined his unit on January 13, 1968, and was one of 3,700 regular replacements to join the Americal Division between January 1 and April 30, 1968. He met his end while serving in the infantry, possibly from an explosive device, like a land mine or “booby trap”. Based on the date of his arrival and what happened in history shortly after, we know that our Hometown Hero must have endured baptism by fire. The largest military offensive by the North Vietnam Army (NVA) and the Viet Cong guerillas, began on January 31st. Named for a sacred holiday, the Lunar New Year, TET, the TET Offensive commenced during the negotiated yearly cease fire, adding to the surprise nature of its beginning. With the war stuck in a stalemate for some time, the communists’ expectation was that all Vietnamese people would rise up to support their offensive and turn the war around. The North Vietnamese simultaneously attacked over 100 South Vietnam locations making January 31st the deadliest day of the entire war.

Our military expert Vic Bary, a decorated Vietnam veteran himself from the same era, was extremely successful with his outreach to the Americal Division Veterans Association. One of the association’s veterans, Gary Johnson, was a member of Company A, Hildebrandt’s company of 175 men. He remembered the action vividly that took Danny’s life. These details that we have uncovered will be new information to every friend and family member of the Hildebrandts. Danny’s unit was part of “Task Force Barker”, which was named after the lieutenant colonel in its command. Their mission was called Operation Muscatine, a search and destroy mission to find elements of the Viet Cong 48th Local Force Battalion, a guerilla unit believed to be in the area. Hildebrandt’s unit moved down from an elevated area known as Buddha Mountain through a series of small groups of jungle settlements known as hamlets. The company had been through the area before with no incidents. On February 13, 1968, at 5:25 p.m., Company A was first engaged by automatic weapons and small arms fire from a hamlet. This was Danny Hildebrandt’s first combat engagement. Gary Johnson’s vivid account created an amazing visual picture. Company A was “on line”, crossing an open field while aircraft bombed the hamlet ahead. Company B, 4th Battalion was set up on Company A’s right flank as a blocking force. As Hildebrandt’s Company A moved to within 50 meters of the hamlet, they became pinned down by heavy machine gun fire, even as the hamlet was being bombed. The gunfire was heavy and sustained and pinned down one platoon (40 men) of Company A. The Viet Cong started systematically “walking” mortar fire onto Company A’s location. Company A would retreat and later reattack only to retreat again. The bombing of the hamlet was replaced by helicopter gunships firing machine guns and rockets into the hamlet. At this point Hildebrandt’s unit would attempt its third attack. Gary Johnson would describe “bullets were like the wind coming from the enemy, the gunships and the blocking forces”. On this attack, Gary Johnson was wounded while trying to clear out a bunker outside the hamlet. Despite the heavy assault of the helicopter gunships which pounded the hamlet until 6:30PM, the enemy didn’t break off until 7:18PM, nearly two hours after the engagement began. Overnight, “Spooky” gunships worked over the hamlet with their 50 rounds per second Gatling guns. In the morning there was no sign of the Viet Cong, they were gone. When losses were assessed, the two companies sustained one American killed (KIA), 9 wounded (WIA), one missing in action (MIA). Sadly, the American KIA was our own Danny Hildebrandt, just 8 days before his 20th birthday and just one month after his arrival in country in Vietnam. Company A had gone into the engagement with 120 men, down from an authorized strength of 180. Vic Bary stated that it was not uncommon for such a short head count during the Vietnam War. When Gary Johnson returned to Company A after treatment for his wounds, he found it to number only 64, suggesting there were further punishing engagements after February 13.

Bad News from Vietnam

Back in New Jersey, the Hildebrandts were informed that Danny was missing in action, and everyone awaited better news from the Army as several days passed. Carol was at work at the beauty salon when her mother unexpectedly arrived, wearing a very telling expression of sadness. “I came to tell you about Danny”, her mother said, “It’s the worst”. Carol remembers breaking down and her mom took her home, where she was embraced by her dad. Her father tried to console her saying that he couldn’t hurt any more if Danny were his own son. Carol took some time away from her job to recuperate from her loss. Typical of the era’s public disrespect to the Vietnam veterans and their families, when her boss from the salon visited her home, he did not express his condolences, but rather collected the salon keys and told Carol that she did not need to return to work. Unbelievably, she was fired.

made for difficult differentiation between the enemy and non-combatant, civilians. These situations created extreme frustration among our armed forces.

The TET Offensive and Public Sentiment

The TET Offensive would continue until March 28th, 1968, and although the body count comparisons and traditional battle statistics would have declared the Americans the victors, many do not consider there to be any winner at all in the two month long offensive. In fact, the events which occurred in this time period created a turning point in the direction of the war. The news coverage of the TET Offensive and vivid accounts of the fierce fighting that the NVA and Viet Cong were capable of, changed public feeling about the war in Vietnam and from that point the U.S. involvement there would start to deescalate. The narrative that had been told from the White House and American media through the past year, that we were winning this war, began to be challenged and was suspected to be false by many outspoken U.S. citizens.

Honoring a Hero

Danny’s body was returned to a Linden funeral home in a sealed casket. His funeral was conducted with full military honors concluding with his burial at Rosehill Cemetery. In the personal belongings returned to the Hildebrandt family were two charred photographs of Carol, which were given to her. Keith Hildebrandt is the only remaining member left of his family and lives in Safety Harbor, Florida, outside Clearwater. He has promised to be with us on Memorial Day at the post-parade ceremony where his brother will be honored. PFC Daniel A. Hildebrandt’s banner will fly permanently next to the granite tablets of Cranford’s Memorial Park, the first time his name has been displayed in Cranford since his passing in 1968. Danny Hildebrandt answered his country’s call when asked and shortly after that, he lost his life while serving. Although not a member of our Cranford 86, he really deserves a place as one of Cranford’s own.

Help Us Get to Number 86

With 47 stories left to write, we urge anyone who has information on any of our Hometown Heroes whose names are listed on the tablets at Memorial Park, to please come forward. The information and photographs that we receive from family and friends is what makes our stories come alive. We print our collection of pictures and stories each year and make it available for purchase after the Memorial Day ceremony. One volume contains all 40 tribute stories and the other will have just the four stories of this year’s honorees to add to your collection. They make great coffee table books for patriotic Cranford residents or Mother’s and Father’s Day presents for Cranford parents. Contact us at info@cranford86.org or call me at

(908) 447-6511

A Final Thought

An interesting anecdote from Carol’s interview helped to re-enforce the fact that Danny Hildebrandt will always be one of Cranford’s Hometown Heroes. Carol feels that Danny’s heart never left Cranford. She believes that if he had returned from Vietnam, they would have stayed in town. Danny had even picked out his dream home on Lincoln Park East. Carol remembers driving by it after his death and seeing that the home was for sale. Talking to him as she does occasionally, she looked up and said, “Hey Danny, your house is for sale.”

Our thanks to Americal Division Veterans Association (ADVA) members Gary Johnson, Leslie Keith, Gary Nolan and Michael McQueen who enabled us to reconstruct the details of Hildebrandt’s final mission. Thank you to Michael Sapara for his determination, encouraging us to tell the story of his Sherman School classmate and for sponsoring the banner of PFC Daniel A. Hildebrandt.