(above) A beautiful oil portrait of Petty Officer First Class Benjamin E. Priddy, age 21 in 1917, as he began his WWI military career serving in Philadelphia’s shipyard.

Meet Major Benjamin E. Priddy, Veteran of WW1 and WW2, One of Cranford’s 86

Lost from HMT Rohna, American Military’s Greatest Loss of Life at Sea by Enemy Action

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, editing by Janet Ashnault, and military proofreading by Vic Bary.

Like many Cranford families this year, the Sweeneys honored a Hometown Hero by adopting one of the Cranford 86 War Veteran flags for Memorial Day 2020. While we knew a little about our selected serviceman, Major Benjamin E. Priddy, from his file at the Cranford Historical Society, we thought it appropriate to dig a little deeper into the life and death of this fellow Cranford resident. The Cranford 86 team has become quite well-versed in its research techniques, one phone call to Cranford 86 researcher extraordinaire Stu Rosenthal was all it took to bring back some exciting facts about Benjamin Priddy. Reacting like a bloodhound that has been given a scent Stu got back to us with information in record time.

(above) A proud dad, Ben in 1934 with Carolyn Audrey (6), and Lawrence (1).

What Stu discovered regarding Major Priddy was extraordinary and left us all dumbfounded. We could not believe that we had never heard of the HMT Rohna, the ship from which our Cranford hero was lost in WWII. Reviewing news articles from that era we realized that hardly any information had been available regarding this incredible tragedy at sea. Stu and I decided immediately that Benjamin Priddy would be our next featured Cranford 86 story. A tale already remarkably interesting before Stu’s discoveries, but the history, or maybe I should say lack thereof, of this hero’s passing, provided for yet another incredible, twisting and turning saga, similar to several others that we have encountered while fulfilling the Cranford 86 mission.

Benjamin Emmett Priddy was born in Brooklyn on July 24th, 1895 to Charles Benjamin Priddy and Henrietta (Foss) Priddy. He exhibited his leadership talents early in life by serving as president of the Young Men’s Association and the Boys’ Brigade of the Bushwick Avenue Congregational Church. Ben attended public schools, starting at P.S. 85 in Brooklyn and graduated first from the Manual Training High School there and then from Pratt Institute of Technology as a draftsman. He worked as a draftsman at Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company in Brooklyn from 1911-1915 and then as assistant chief draftsman at Cameron Machine Company in Brooklyn from 1915-1916. In 1917 he relocated to Muskegon, Michigan for a position at Shaw Crane Company as a mechanical designer and checker. He married Lila Wyckoff of Brooklyn while living there.

(above) The 461-foot-long HMT Rohna in her glory days. By 1943 she had been used as a military transport ship for four years and was described as a floating rust bucket, suffering badly from lack of maintenance. On November 25th, 1943, the day after Thanksgiving, she would be struck by a guided glide missile and sink in 90 minutes. 1015 American soldiers would perish on that Black Friday.

In 1917 after WWI had been raging in Europe for three years, submarine attacks on American shipping caused Congress to declare war on Germany. Ben had expressed a desire to join the service. He made a statement that if he did, he wanted to “see action”. In May of 1917 at the age of 21, he enlisted into the Navy and quickly rose to the rank of Chief Machinist’s Mate, an operating engineer position. Probably not fulfilling his initial vision of military service, Ben primarily was inspecting steel products at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard in South Philadelphia. In 1776 Philadelphia boasted the first shipbuilding yard in America and by WWI the yard had relocated within the city and grown to be the largest in the world. Ben was stationed in Philadelphia with his new wife for the duration of the war and his goal to “see action” during his military service in WWI never was attained, instead he used his valuable skills and knowledge in the shipbuilding arena and dutifully served to strengthen and grow our country’s Navy. In 1920, while still stationed in Philadelphia Benjamin and Lila welcomed a daughter, Lorraine Carolyn, she would be their only child.

In 1924, we find Benjamin living in East Orange, New Jersey, married to Meliora “Millie” (Ogle) Priddy and employed by a manufacturer of automated road building equipment. In 1925, the couple purchased a house in Cranford and made it their home for 19 years through Ben’s career with multiple companies in the asphalt industry. They raised two children at 210 Retford Avenue, Carolyn, born in 1928 and Lawrence in 1933. During the early segment of this period, the mass production of affordable cars and the need for roads and highways made the asphalt industry a booming business. Benjamin’s education and work experience put him in a position for success in that field. In the early 1930’s the Great Depression changed things somewhat. Even though there were some government programs which propped up the road building business, every industry, including the asphalt business was adversely affected. In 1935 Ben would take a job with W.M. McIntosh Company of Richmond Virginia, a national asphalt firm. He would rise to be Vice-President and Director of Operations for the entire East Coast. In 1941 after the outbreak of war, another economic factor affected the asphalt industry. Just as gasoline, rubber, coal, and nylon were restricted in their domestic use, asphalt was as well. The need for the mass construction of paved runways overseas all but eliminated the building of roads and highways here at home. Although I was aware of war-era rationing programs, I had never thought of how one’s income would be affected if their livelihood was associated with one of those industries.

(above) In possibly one of his son’s first military salutes, Ben is saluted by Lawrence, age 9, in Cranford before shipping out for his second basic training. Lawrence would go on to serve in the US Army.

Along with the know-how to gather information from on-line databases, Stu Rosenthal also has great skill in finding family members of our Cranford 86. He certainly did not let us down on the Benjamin Priddy story and unbelievably he was able to locate Benjamin Priddy’s son, 87-year-old Lawrence Priddy, an Army veteran, living in New Jersey. Ben’s son Larry told us that during WWII his father was approached by the Army with an offer to enable him to put his skills to use in the military. So, in October of 1942 Ben became a part of an elite group of Americans who stepped up to serve our country in not one, but two World Wars. At the not-so-young age of 47 he enlisted once again into the military, this time with the Army Air Force. He was commissioned a Captain and was sent to Camp Claiborne in Louisiana for a refresher course, then to Richmond Air Base in Virginia. Ben then proceeded to Dyersburg Army Airfield in Tennessee, the home of the newly formed 853rd Engineer Battalion. Their main duty would be to build airfields for the 20th Air Force and it was with the 853rd that Captain Benjamin Priddy would enter the battle theater of North Africa in October of 1943.

After just two months in North Africa, Benjamin was promoted to Major and put in charge of runway construction and repair for the Army Air Corps. He then received orders to ship out to the China Burma India (CBI) Theater with 792 Army engineers from the 853rd. Their purpose there would be to construct air strips to accommodate B-29 Superfortress bombers which flew missions over a very dangerous airlift route across the Himalayas into China nicknamed “The Hump”.

He sent a letter home to Cranford on November 18, 1943, before the trip from Africa began. In it, Ben told his wife Millie not to worry if she did not hear from him as he shortly would be enroute to a new station.

(above) Reentering the armed forces after a 23-year gap, forty-seven-year-old Captain Benjamin E. Priddy is pictured at Camp Claiborne in Louisiana in 1943 as he completed his “refresher course”. As an Army officer in the Air Corps, he was to be in charge of runway building and repairs in North Africa.

The 853rd along with several thousand other military personnel converged on Oran in French Algeria where four converted ocean liners awaited their arrival. Ben’s unit was assigned to the HMT (His Majesty’s Transport) Rohna, a British India Steam Navigation Company ocean liner that was converted into a military transport ship four years prior. When in commercial use, the Rohna would accommodate 100 berthed passengers. This trip it would be carrying 2193 passengers and including the crew, total number on board would be 2,388. The overcrowding was immediately apparent, and some rearranging of assignments occurred in order to allow the 853rd to bunk together, a move which would prove fateful to this battalion of engineers. Every square inch of deck space was covered by a soldier or his gear and many slept on the upper decks as well as in the corridors.

In the story that we wrote about the USS Indianapolis and the plight of Patrick Castaldo, we followed the survivors’ memoirs from the book In Harm’s Way. For this open sea tragedy, we had a similar guiding book, Allied Secrets…The Sinking of the Rohna. The book’s description of the Rohna provides important insight as to what the battalion experienced during their fateful voyage as well as hints as to what would become its ultimate destiny. It was stated that the Rohna was suffering badly from a lack of maintenance. There was more rust visible than paint. Even though there were dozens of cats on board to control the rodent population, there were several generations of rats living amongst the passengers. The strong smell of fuel oil battled the stench of vomit as the dominant fragrance that permeated the ship. Many American soldiers, who were accustomed to quality accommodations on US transports, rated the Rohna unfit for human habitation. The first day at sea was November 25th, Thanksgiving Day, and this being a British India ship, Thanksgiving was not celebrated. There was no turkey dinner awaiting the men, instead, their meal was brought to the bunk room in buckets and consisted of creamed chipped beef dished into mess kits with a ladle. There was a mention of a cart of fresh fruit that passed through crowds of enlisted men which initially brought cheers, only to be realized that it was for officers only. This made us feel that Major Priddy might have been eating a little better than the average soldier.

The Rohna was part of Convoy KMF-26 which had a total of 24 ships in a formation of four across and six deep. It was one of four military transports escorted by an assortment of British and American defensive ships, mostly corvettes, destroyers, minesweepers, and frigates. Above, the Free French Army and the British Royal Air Force provided air support. The Rohna was placed in the “Coffin Corner”, named for that position’s vulnerability in past convoys. The Rohna was also the only ship not flying “barrage balloons”, devices that entangled invading enemy aircraft or their weapons. The American soldiers, who made up the majority, were superstitious about livestock being on board a military ship. The Indian crew kept numerous farm animals and even the Captain had a pet goat that was the mascot of the ship, undoubtedly causing unease amongst the Americans.

Going into day two, information about their route was circulating amongst the men. The convoy was going to pass through an area known locally as “Suicide Alley”, a vulnerable stretch of the Mediterranean from Algeria to Tunisia that was known for air attacks from German-occupied France.

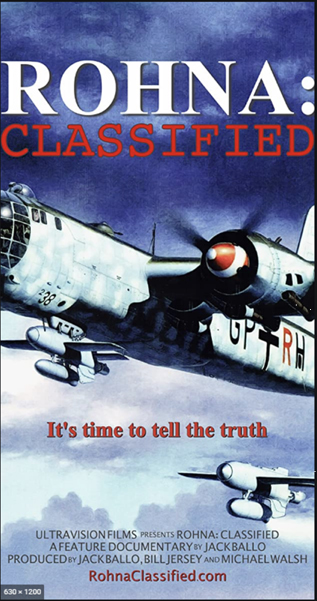

(above) The movie poster for the upcoming documentary being created by NJ filmmaker Jack Bollo. Pictured here is the He-177A Griffin bomber that carried the glide missiles. The film is scheduled to be completed by December 2020.

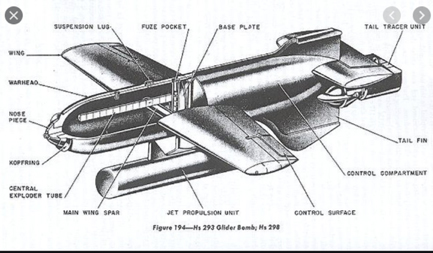

At 4:30 pm on Friday November 26, 1943 off the coast of Bougie, Algeria, Convoy KMF-26 approached “Suicide Alley”. Almost as if on cue, from the northwest a “staffel”, German for squadron, of thirty to thirty-five Heinkel He-177A Griffin long-range bombers approached. Some of the bombers carried traditional “vertical” 500-pound bombs, but twenty-one of the bombers were carrying Hitler’s latest secret weapon, the HS 293 remote-controlled chemically propelled glide missile. The HS 293 looked like a small winged plane and was attached to the bombers under each wing or directly under the fuselage. Once launched, it was visually controlled with a joystick type of device by a crew member of the plane from which it originated. Although in development for several years under German engineer Herbert Wagner, reports revealed that it was only since September of 1943 that a series of attacks on Allied ships in the Mediterranean could be attributed to the new guided bombs. The attack on the convoy had two fifteen-minute waves. The first wave saw many vertical bombs splash next to the ships answered by cheers from the men crammed below deck, viewing the action through portholes. Two bombers were downed by anti-aircraft guns from aboard the defending ships as well as by the guns mounted on the Rohna. A dozen guided missiles were also launched and fell into the rough sea, none hitting their targets. Many misses were attributed to the allied defenses that had been created since the inception of the guided glide missiles. At least six of the guided bombs were successfully drawn off target by new radio-jamming equipment on some of the convoy escorts and heavy smoke screens that had been released, limiting the visual aspect of the missile’s guidance system. The second wave of the attack started after a 30-minute break, with much of the same activity. Still not one ship had been hit. The French spitfires above were also successful in downing two of the Griffin bombers. It would seem that the KMF-26 convoy was close to surviving the well-armed assault from the Luftwaffe’s latest technological creation. In the last minute of the second wave, an experienced German pilot named Hans Dochtermann, launched his second rocket boosted glide missile and it was successfully steered as it strafed across the wave tops and approached the Rohna at 340 miles per hour. Survivor accounts tell that many watched through the portholes as the missile approached, it seemed that it might miss the moving ship. Tragically, it struck the aft on the port side, fifteen inches above the water line, directly into the kitchen, engine room and the bunk area that housed all of the 853rd Engineering Battalion. Its delayed fuse caused the 650-pound bomb to explode inside the cabin. Eyewitness reports say it made a seventy-five-foot hole that went right through the ship. Men were jumping overboard, some with just a life vest, into rough seas. From the point of impact at approximately 6:00pm, it took just ninety minutes for the Rohna to sink. The USS Pioneer, a minesweeper, was first to the rescue and would nearly capsize itself with the weight of 650 survivors. Several other ships also eventually made their way over to aid the Rohna. In total there were 966 survivors rescued, 35 of which died of their wounds on the journey to on shore hospitals. Those 35 were buried together in Carthage, Tunisia, at the North Africa American Cemetery, where a memorial to the American sailors and soldiers lost in the Mediterranean Sea is maintained still today.

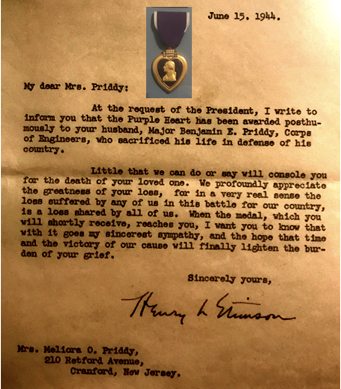

(above) Military letters sent to family members after a tragic loss of life can sometimes come across as being a bit cold. We thought that this letter written by Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War, was one of the most well-written letters of its kind, worthy of sharing.

Eyewitness estimates report that 300 men were killed instantly, flames reached up over 100 feet and the ship started leaning severely as it started to take on water. Suffering from the lack of maintenance, like much of the equipment on the Rohna, the ship’s 22 lifeboats were in poor condition from the start. The blast from the attack then destroyed or damaged most of them. Some that were still usable were unable to be released from their hardware and the lifeboats on the port side could not be launched due to ship damage. Ultimately, only eight lifeboats could be deployed and all but two of them that did get in the water were quickly overloaded, swamped, and sunk.

It was reported by surviving soldiers that immediately following the abandon ship announcement, the Indian crew was the first to do so. No assistance was offered to military passengers as would be the usual protocol. This led to additional embarrassment over the incident for the hosting British government. Of the 30 officers and 793 enlisted men of the 853rd who boarded the Rohna, it was discovered that 10 officers and 485 enlisted men were missing in action when the chilling roll call was read to the regrouped survivors. Our Major Benjamin Priddy was one of the names, that when read, had no response. Major Priddy would be the highest-ranking soldier to perish on this tragic day. The 853rd had lost 62% of their battalion. In total 1,138 were lost, 1015 were American soldiers. It was the greatest loss of U.S. life at sea due to enemy action in American history. The USS Arizona suffered a greater loss of life, but it was not at sea and those lost from the USS Indianapolis numbered 880.

(above) Ben in his fatigues at Camp Claiborne.

Amazingly there was a Cranford 86 member in the three largest tragedies in American military history, Patrick “Perk” Castaldo on the USS Indianapolis, Keith Jeffries on the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor and now Benjamin Priddy on the HMT Rohna. In all of these stories, during the heart-pounding description of the chaos that ensues during an open sea disaster, a feeling comes over me and a thought comes to my mind. Writing the details of the moments before each ship sank, I have paused along the way to think, where is our Cranford hero now? Once again, that same feeling came to me. Where was Ben during all of this?

As they were recuperating from their wounds, each of the 931 Rohna survivors was informed that the happenings of the disaster that they had just endured had been deemed “Classified” by the Army. A strict order of secrecy was given to each soldier and they were warned, if anyone spoke a word of it to anyone, even amongst themselves, or sent any news of the event home they would be court-martialed. No family member of the deceased was informed about the fate of their loved ones for over a month. Many families were becoming suspicious that something had gone wrong since the normal flow of letters home had stopped. Finally, a vague telegram was sent to each Gold Star family simply stating that their loved one perished at sea on a transport ship and no further information was available. Some were given information insinuating their ship had been a victim of a torpedo strike. The “Classified” status of the incident was soon updated to be “Permanently Classified” due to persistent pressure by the British military.

(above) Millie Ogle, a Jersey girl from East Orange was the reason that Ben Priddy left Brooklyn. The couple resided at 210 Retford Avenue with their 2 children until Ben’s passing in 1943

The news of Major Priddy’s missing status reached Cranford on December 28th. There was no military service, no write-ups or mention of the incredible event in local newspapers. At the time of Benjamin’s death his daughter Carolyn was 15 and his son Lawrence was 10. Eight years later Millie passed away, the same year that Larry would head off to Rutgers University. Nearly fifty years would pass before Ben’s children would even hear the name HMT Rohna or hear the fate of their brave, dedicated father. By the early 90’s some of the silenced survivors had started to share their secrets. Ben’s son Larry was retired in South Carolina when he saw a newsletter from the office of Congressman Strom Thurman about the transport ship that was sunk off French Algeria in 1943. Thurman welcomed family members to contact him for more information. It was then that the Priddy family first heard the still vague details of the Rohna’s sinking. Then, on CBS’s Sunday Morning’s Charles Osgood’s national radio broadcast on Memorial Day 1993, nearly fifty years after the tragedy, the story of the Rohna was told in detail to the American public. Carlton Jackson and Michael Walsh, historic authors, started interviewing members on the survivor list and used them to create a few books, two of which were Allied Secret: The Sinking of HMT Rohna, published in 1997 and Rohna Memories, Eyewitness to a Tragedy in 2005. Another group, led by Jack Ballo, a filmmaker from South River, NJ, collected interviews and is in the process of producing a documentary of the open sea tragedy, which is due to be completed by December of 2020. Seventy-seven of the lost soldiers were from New Jersey, one was from South River. We reached out to Mr. Ballo requesting a possible showing of his film in Cranford, on Memorial Day weekend 2021. He responded, and although the Covid-19 crisis has slightly delayed the film’s anticipated completion date, Jack Ballo has promised to fulfill our request.

Although the sinking of USS Arizona and USS Indianapolis are far better known, the greatest loss of U.S. life “at sea,” due to enemy action, was not suffered by the Navy, but was actually suffered by U.S. Army troops aboard the HMT Rohna. But no history of WWII mentions the Rohna; not even a recent Encyclopedia of World War 2. Officially, the destruction of the Rohna was shrouded in secrecy during the war because neither the British nor the American governments wanted their populace to know that the age of guided bomb warfare had arrived, and that their sons were its first victims. Still, even many years after the war, very few details of the Rohna were released and some people believed the real reason for the information blackout was because the American government did not wish to embarrass the British government.

(above) In happier times, Ben Priddy, pictured with son Lawrence and daughter Carolyn, enjoys a Florida beach vacation with his family.

In addition to locating Ben’s son, Lawrence Priddy, Cranford 86 also contacted Ben’s granddaughter (daughter of Lawrence), Jeanne (Priddy) Viscito, who is the former mayor of Berkeley Heights and still lives in New Jersey and Ben’s grandson (son of Lawrence), David Priddy, a Naval Academy graduate and former Naval helicopter pilot, living in Minnesota. They all helped to put the life story of their father and grandfather together for us. When we started to create his profile we only had an unbelievably bad newsprint photo, but fortunately the family has provided us with amazing photos from Ben’s service in 1917, a photo from his marriage to Millie and many others. In our conversation with Benjamin’s granddaughter Jeanne we found out that Ben’s daughter Carolyn spent the last days of her life here in Cranford at Cranford Hall Nursing Home on Lincoln Park East until she passed in 2011. After their family’s approval of our story, Jeanne Viscito told us that she had learned more about her grandfather in the last two days than she had ever known before. It is feedback like that, that fuels our team as we surge forward in our mission. The family has promised to join us next Memorial Day for the dedication of Major Priddy’s street banner when we hope the 100th Memorial Day service and parade will be able to take place.

The American patriot Nathan Hale made a famous quote before being hung by the British for being an American spy, “I only regret, that I have but one life to lose for my country”. Benjamin Priddy’s one life was offered twice to his country, in two different wars, in two branches of the armed services and in two different decades, a rare occurrence. We are blessed as Americans to have such brave dedicated men that loved our country so much, that they would choose to put their life in danger so that all Americans can live a life of freedom. Major Benjamin Priddy is truly an American patriot and we owe him and his family who was left here in Cranford without him, a huge debt of gratitude. It is unfortunate that it has taken so long for the people of Cranford to learn of this amazing story of dedication and sacrifice. Major Priddy is truly a Cranford Hometown Hero.

Special thanks to Christina Ponte for sponsoring the banner of Major Priddy. I met Christina at Memorial Park this year as I was sitting quietly near the 27 Cranford 86 banners on display there for Memorial Day. Recently introduced to me and fresh in my mind, I was able to relate the Priddy story to her. Coincidentally, she had already sent in money to sponsor a Cranford 86 hero but had not yet selected one. My chance meeting with Christina made her mind up as to which hero she would choose. To add to the coincidence, both she and Benjamin Priddy are graduates of Pratt Institute.

The history of the designer of the glide missiles, Herbert Wagner is quite interesting. Wagner was captured not long after the sinking of the Rohna and was rushed to Washington D. C. to lead an American team of engineers to develop guided missiles that would be used against Japan. He remained a German citizen but lived in California until his death at age 82 in 1982. The veteran pilot Hans Dochtermann was also taken prisoner shortly after sinking the Rohna, he spent the rest of his life apologizing for the grief he caused the survivors and family members of the deceased. Dochtermann even attended and spoke at many survivor reunions.

See the links to additional historical details and photo of the Benjamin Priddy story. Links to additional history of the HMT Rohna.

(above) The last Priddy family picture taken before Ben left for North Africa.

(above) Born and raised in Cranford, Lawrence and Carolyn Priddy in their backyard.

(above) Captain Priddy relaxing at Camp Claiborne, getting used to his new work clothes. After 23 years in the private sector he entered the Army Air Corps to command the building and repair of runways.

(above) Meliora Priddy, was called Millie by everyone.

(above) Ben Priddy, age 29, as the handsome groom that married Meliora Ogle in 1924. The couple moved to Cranford the following year and made it their home for 19 years.

(above) The HMT Rohna departed from Oran, Algeria and headed east toward Tunis, Tunisia. Her planned route was to enter the Suez Canal on her way to the CBI (China Burma India) battle theater. Long-range bombers from German-occupied France travelled across the Mediterranean Sea and attacked the convoy off the coast of Bougie, Algeria. This map helps put the attack into perspective.

(above) Hitler’s secret weapon, the Hs 293 glide missile, a remote-controlled flying 650-pound bomb.

Hs-293 , a clip demonstrating the Hs-293

Henschel Hs 293 Anti-Ship Missile

A detailed explanation of the Fitz-X and the later more advanced Hs-293

The promotional website for the upcoming documentary for the HMT Rohna