Meet Pvt. Frederick E. Heins, Pvt. Sydney J. Craig, Pvt. George H. Haskins and Pvt. Robert R. McGregor, Four of Cranford’s 86, and their stories from WWI and The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, editing by Janet Ashnault, and military proofreading by Vic Bary

In the fall of 2019, after receiving sponsorship from the Buontempo family, Cranford 86 brought you the story of Juan Bargos. As the only residents of Bargos Place, the Buontempos wanted to introduce to Cranford the hero for whom their street was named. Juan Bargos was a young Mexican national, who arrived in Cranford in 1894, with his recently widowed mother. The way Juan overcame adversity in the incredible journey of his short life touched every reader of the Cranford Monthly, in the October 2019 issue. Within their first year in Cranford, the Bargos’ new home on Willow Street tragically burnt to the ground and Juan’s mother passed away days later. In a life that presented seemingly an unprecedented series of obstacles, this young man rose up and overcame almost all of them. While serving our country in World War I, during the Spanish Flu pandemic, Juan was on a trans-Atlantic military transport ship bound for the European battle theater. He was part of an armored tank unit and was one of many who contracted the H1N1 virus. Juan would meet his end at the age of 30 on October 5th, 1918 when he succumbed to this invisible enemy. (Read the Juan Bargos story at Cranford86.org).

As a father of a Philadelphia college student, I had the opportunity to take a guided historical bus tour around downtown Philadelphia. The story of the Philadelphia-centered Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 fascinated me and sparked my historical curiosity. Our tour guide gave a graphic depiction of the weeks following a war bond fundraising parade held in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1918. Many had thought that the parade should have been cancelled out of caution for the developing contagion of the H1N1 virus. In just a few weeks, post-parade, 12,000 would die in Philadelphia. The tour guide’s description of the nightly pickup of bodies which were stacked up at curbside is still imprinted in my mind. Just weeks after the tour, I found myself amidst the Juan Bargos story and its connection to this historic American tragedy.

The Spanish Flu, as it was misnamed, actually originated in the United States. By government order, no news agency was free to publicize the sickness that had revealed itself in March of 1918, at a US military base in Kansas. At the time, the fight against Germany was not going as well as the world might have liked, and it was feared that hysteria over the virus would possibly affect the war effort. Spain, a neutral country, had no restrictions on their press and it spoke freely about the virus. Estimates report that the virus killed between 17 and 50 million people globally and 675,000 Americans in the two-year pandemic. But when 8-million Spaniards and their King, Alphonso XIII became ill from it, the media in Spain gave it full coverage and even blew it out of proportion. They called it the Spanish Flu, it would go on to kill an amazing 2.5% of the worldwide population of 1.3 billion. Put in today’s perspective, with the current world population, that would compute to a death toll of 19,500,000. The H1N1 virus of 1918 is similar to Covid-19 in that it was highly contagious and very deadly. For both of these viruses, it was initially a mystery as to their origin and also as to how they spread. Upon onset of each of the pandemics, no vaccine existed to protect the population and there were many unknowns as to the proper treatment of patients. Unfortunately, thousands of those who were first afflicted, would die. The antibiotics and ventilators that helped to treat Covid-19 sufferers were not yet available in 1918. Despite the similarities of the 2 viruses, they differed in regard to the categories of people that fell vulnerable to each of them. The Covid-19 virus preyed mostly upon the elderly and H1N1 brought rapid death to healthy people ranging in age from 15 to 40. While criticism in 2020 was aimed at officials that mishandled Covid-19 patients in assisted living facilities, in 1918 most of the blame was pointed at the military for placing our fighting forces in close quarters on land and at sea. Due to the lack of electronic media and a 24/7 news cycle, the officials that mishandled the virus in the early 20th century were somewhat shielded from pointing fingers, quite unlike what the leaders of our country today are experiencing.

Juan Bargos was not the only member of our Cranford 86 honor roll to have perished from the Spanish Flu during WWI. We believe that there were four others that were victims of this wartime virus. The military archival records available to us for most of our WWI heroes are not as extensive as those from the more recent wars. Frequently, all that can be found is a simple index card containing minimal information and a short paragraph written by a family member in answer to an inquiry made by a military clerk after their death. Sometimes the record contains a portrait but sometimes it does not. The Cranford High School yearbook, the Golden C, has been a wealth of information and photographs for our Cranford 86 profiles from WWII through the Vietnam era. Unfortunately, the yearbook’s inaugural issue was not published until 1932. The two local newspapers in 1918 were The Cranford Chronicle and The Cranford Citizen. Often, the printed obituaries from these two publications lacked the level of detail of circumstances and life stories, of which we had become accustomed to in later news coverage of lost military men. In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic with all of the daily rituals and conversations of the virus still filling our days, we thought this was the right time to tell the stories of these additional four Hometown Heroes. They stepped forward to defend our American way of life and lost their lives in doing so. We have come to the realization that we may never have all the details to completely introduce the stories of some of these brave men but sharing what we know about them is still a worthwhile effort. We hope that in the future, additional research will allow us to go back and fill in the blanks. The nature of our website and the yearly reprinting of our tribute books allow us to update the stories as needed. Our hopes are that someone who reads our work may have additional facts or enable us to make a connection with a family member that possesses a photo or any information that will help our researchers. We have chosen to tell the stories of our four Hometown Heroes who fell victim to the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, in the order in which they perished.

Frederick Edwin Heins was born in New York City on April 11, 1894. He and his family relocated to Cranford where they moved into a beautiful Victorian home at 209 Holly Street. He attended Cranford schools through high school but finished his education at the Cheshire School, a prestigious boarding school in Cheshire Connecticut. On November 25th, 1917, six months after the US entered the war, Fred enlisted into the Army and shipped out to Fort Slocum in New Rochelle, NY, on the western shore of the Long Island Sound. From there he was sent to Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas where he joined the 241st Aero Squadron. Shortly after beginning his training in Texas, he was exposed to the Spanish Flu and succumbed to the virus on February 7th, 1918. He died at the Army hospital at Fort Sam Houston, also in San Antonio, at the age of 23. The cause of death is listed as lobar pneumonia and empyema, the latter being described as “suffocation from liquid and pus in the respiratory system”. His body was sent back to Cranford and he was buried in a prestigious section of Fairview Cemetery in Westfield, beside his mom and dad, Minnie and John, his older brother by two years Harry, and his younger sister by one year, Mabeth. Fred Heins had served just 73 days in the US Army.

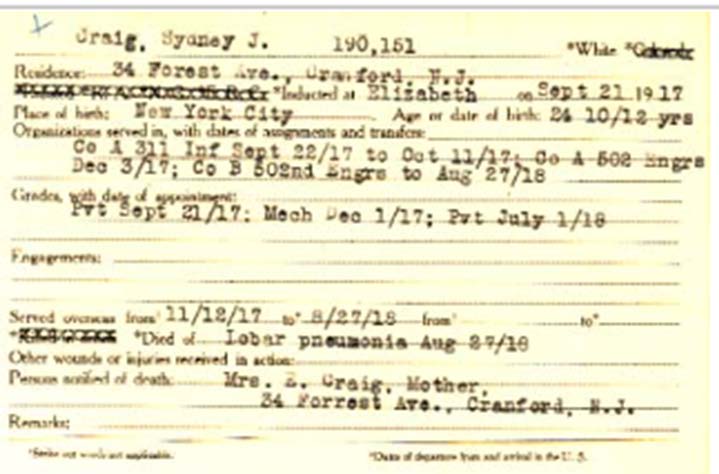

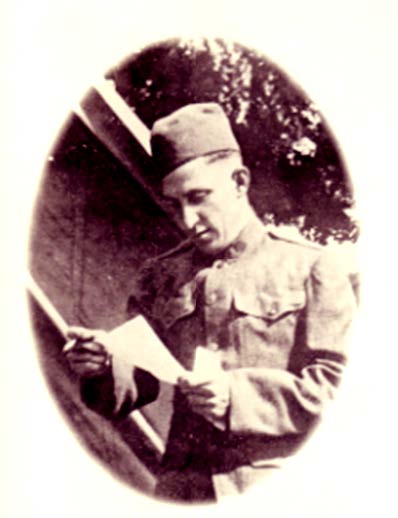

Private Sydney Jerome Craig was born in Brooklyn, NY on November 18th, 1893. His family moved to Cranford and settled at 34 Forest Avenue, a beautiful home on the corner of North Avenue across the street from the Trinity Episcopal Church. On September 21st, 1917 he enlisted into the Army in Elizabeth and was sent to Fort Dix in Lakehurst, NJ, then to Camp Merrill in Tenafly, NJ where he joined the 311th Infantry Division Company B. After one month Sydney joined the 502nd Division of the Army Corps of Engineers as a mechanic. On November 11th, 1917 he shipped out with his unit, to St. Nazaire, France as a part of a major construction project to build the world’s largest military hospital complex. It would have 400 more beds than the largest military hospital in existence at the time, which was located in England. St. Nazaire was the disembarkment port for almost all US troops entering Europe and the building of the hospital itself would only be a part of the project there. Railroads and highways to support the complex were to be built, along with complete infrastructure including a dam and a water treatment plant.

Our researchers located letters that were sent home from Army engineers in Sydney’s unit from within the same time period in which Sydney had served. American GIs were raving about the wonderful treatment that was being provided by the grateful French people who had been under German occupation for over three years. The food and wine were said to be extraordinary and plentiful. There were legal brothels that were controlled by the Army for the safety of the soldiers. The construction project was far away from any action and the engineers were boasting that the deployment could not be safer. In one letter, the engineer stated that he would certainly soon be returning home safely. What they had not figured on was that the crowded transport ships that arrived daily from America were contaminated with H1N1. A person infected with the virus many times would die within one to three days after onset of symptoms.

On August 27th, 1918 Sydney died at the St. Nazaire Hospital, the cause of death was the familiar lobar pneumonia. He was two months short of his 25th birthday. Afterward, Sydney’s brother Gus named his first child in honor of his brother. Ironically, Sydney V. Craig is also one of our Cranford 86. He was a participant in the D-Day invasion on June 6th with the 747th Tank Division and was killed in action on July 15th, 1944 in Normandy, France.

A military funeral for Sydney Jerome Craig was held on September 25th, 1918 at St. Michael’s Catholic Church. After the service, in a procession led by Cranford VFW Post 335, Cranford’s American Legion and hundreds of townspeople walked to lay flowers at Memorial Park (then located at the corner of N. Union and Springfield Avenues, now the 9/11 Memorial), and then past the family home on Forest Avenue. At the city limits many privately owned cars transported the crowd to the cemetery in Plainfield. Craig Place off of Orange Avenue was named in honor of Sydney J. Craig.

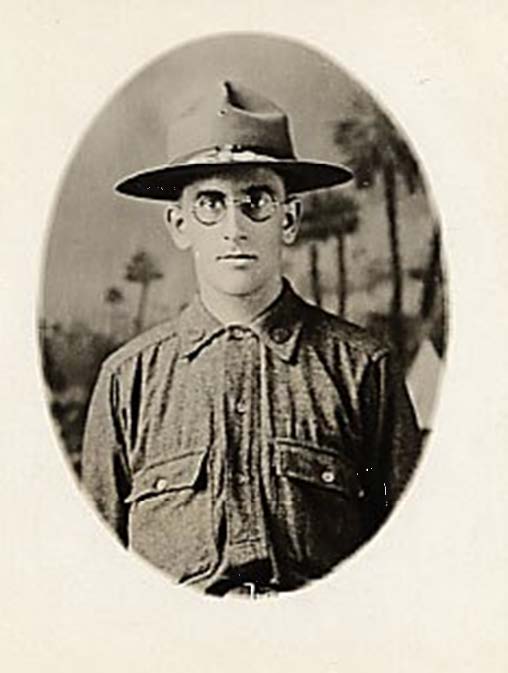

Private George H. Haskins was born in Brooklyn, NY and moved with his family to 28 Beech Street in Cranford, he was one of six children. The information that we have on George is limited. A letter from his family as a reply to the government’s questionnaire about the details of George’s life was very short. In it, Grace May Smith, his older sister by 16 years, stated that she could not provide much detail about his death because he died in Jacksonville Florida from the “great plague which went through our army.” She continued, “He was training with the Master Corps and was getting ready to be sent abroad. A day or two before he was set to sail, he died. He was anxious to do his part and I know that if he lived he would have been a great service to his country”. I can only surmise that she missed the point of the questionnaire as this would have been a great opportunity to document a little about her brother’s life. If only she knew that her answer might be all of the history that would be left behind a hundred years later, she would have expanded her paragraph. George’s military description card told us little as well. It stated that he enlisted at Fort Slocum in Rochelle Park, NY on May 26th, 1918. He was shipped to Camp Johnson in Jacksonville Florida on August 30th as part of a training company, where he stayed until his death on October 16th, 1918. Thankfully, the card did have a wonderful portrait of George in his uniform. His cause of death was stated as bronchial pneumonia and he was just 21 years old. A private funeral service was held on a Saturday afternoon at the home of his sister at 28 Beech Street. Haskins Avenue bordering the Bloomingdale School playground was named in memory of George H. Haskins.

In our efforts to introduce the Cranford 86 victims of the 1918 Pandemic, we struggled to find information. It seems that each story contains less detail than the preceding one. The research folder for the last victim of the Spanish Flu is the sparsest. The 1900 US Federal Census told us that Robert R. McGregor was born in Providence, Rhode Island. His parents, Alex and Ann McGregor were immigrants, his dad from Scotland and his mom from Germany. The census record revealed that Robert was born in January of 1900. We also found some information from the 1918 Cranford Directory. Robert R. McGregor was listed as living at 329 Centennial Avenue apparently out on his own at age 18. From Robert’s obituary, we learned that his parents had moved to Summit and that Robert enlisted in the Army at the beginning of the war along with Ernie Schultz, who we believe to be another Cranford youth. Another clue to Robert McGregor’s military involvement came from the Burditt card files at the Cranford Library. The Robert McGregor card mentioned that he died “near the Mexican border with the 17th Cavalry Company on November 17th, 1918”. Stu Rosenthal found that the home of the 17th Calvary was Fort Bliss in El Paso Texas, which is on the Mexican border. The 17th Cavalry along with several other cavalry units had been fighting Pancho Villa since 1916. During this era, the calvary fought primarily on horseback, see the link to the video at Cranford86.org. During WWI more than 4,500,000 horses were being used by 2,000,000 soldiers. Incredibly, as many as 45,000 horses could be killed in a month. Pancho Villa was the leader of a revolutionary group that the US government had chosen not to support in the Mexican Revolution. Villa had made several attacks across the border and killed US civilians and military personnel. Robert McGregor was not fighting the Germans in France or even training in the US to prepare for the European conflict as had been insinuated in his obituary, he was involved defending against the most recent attacks on American soil across the Texas border. There was a huge outbreak of the Spanish Flu reported at Fort Bliss in late September 1918. It started from infected soldiers who were being transported to Texas in crowded troop transport trains from eastern US cities. The infection peaked in October 1918, with some 400 deaths per week. The hospitals were severely overcrowded, with numerous doctors and nurses being a large part of the death toll. Mandatory mask laws were in place and all public gatherings were banned including weddings and funerals. The infection curve turned down in late November 1918, coinciding with Robert McGregor’s passing on November 17th and the end of WWI, Armistice Day being November 11th, 1918.

The last source of information about Robert came from a directory of war dead from the state archives in his home state of Rhode Island. It stated his “Nativity” as Cranford, NJ, which conflicts with our census record, with his cause of death listed as bronchial pneumonia. Stu Rosenthal, our lead researcher, was able to find a photo of Robert’s gravestone. It presents another piece to the puzzle of the story of Robert McGregor’s life, that we hope someday can be unraveled. Robert is listed on a family headstone, in a Rhode Island cemetery, what is a bit strange, is that it is not his family.

We are honored to bring you the story of these four young Cranford servicemen who perished in the last severe pandemic which affected our country. The research and reading that Stu Rosenthal and I had conducted for the Juan Bargos profile gave us plenty of insight as to the potential dangers of the 2019 coronavirus, which many were saying was no more harmful than the yearly flu. We knew how serious this respiratory novel virus could be. I remember sharing some statistics from the Spanish Flu with my employer when I supported the stay at home order in March of 2020. He inferred that it was all blown out of proportion and that with the medicine that we have nowadays, it could never happen again. He has since apologized for his criticism to my warnings. I knew that the second wave in the fall of the 1918 Flu Pandemic took twice as many lives as did the first. When I mentioned that to anyone who would listen, most said they were unaware of that fact. The second wave of Covid-19 also turned out to be more deadly that the first.

When we first began telling the stories and introducing the men whose names are listed on the tablets at Memorial Park, I had thought that this was a list of soldiers who were killed in action. I soon understood that not to be the case. The tablets list the names of any brave person who stepped up to fight for our country’s freedom and lost their life during that service. The situation that caused their death is not considered and they are all to be honored in the same manner. Each of our Cranford 86, like all members of our armed forces, offered themselves to our country for a contracted period. No matter how their life was taken from them, it was no less a loss for them or their loved ones. In the Civil War more soldiers fell to dysentery than to bullets or cannon balls. In WWI the Spanish Flu took more lives than were lost in battle. On our list of 86, there are several heroes who fell to friendly fire, motorcycle, jeep, and auto accidents and several from cancer and other diseases. Regardless of how they met their end, the patriotism and bravery that these men exhibited by coming forward when our country needed them most, deserves our appreciation and respect. The Cranford 86 team will continue its mission to honor all of our 86 until the last story is written.

If you have knowledge of any of our Cranford 86, we invite you to please come forward and help us to fill in the blanks of our heroes’ life stories. Email us at info@cranford86.org or call (908) 272-0876.

An incredible article with many details of how the pandemic of 1918-1919 affected Cranford was printed in the Cranford Historical Society’s newsletter, The Mill Wheel. This newsletter, largely written by our military proofreader and society curator Vic Bary, is printed 5 times a year and is full of Cranford history. It is sent electronically or in print to the members of the Cranford Historical Society. We have made Vic’s article available on Cranford86.org. It was an important resource for us in writing this story, it contains many additional pertinent facts and statistics. We also urge our readers who enjoy history or have roots in Cranford to consider a membership in the Cranford Historical Society, this important steward of our town’s history, membership fees are nominal. The historical society is currently debuting their new, interactive website which features many interesting and informative articles and photos as well as links to all of the Cranford 86 stories written to date. Visit it at Cranfordhistoricalsociety.org.

YouTube link to a 1918 Cavalry training silent video from Fort Sam Houston in Texas that would be similar to the unit training that PVT Robert McGregor was involved with. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=QxOggtbzMJo.

The Mill Wheel – News and Stories from the Cranford Historical Society