Meet 1st Lieutenant Richard A. Borrell, World War Two B-26 Bombardier, One of Cranford’s 86

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, editing by Janet Ashnault, military proofreading by Vic Bary.

As our group of researchers and writers endeavors to uncover the life stories of the 86 men that we honor each Memorial Day, we continue to be amazed with our findings. As many of our readers have pointed out to us, the development of engineering marvels and how our heroes were involved with them, often becomes the underlying plot line which makes our Cranford 86 narratives both interesting and informative. The story of 1st Lieutenant Richard Borrell and his role as a B-26 bombardier illustrates that idea, how our Cranford boys, manning high-tech positions, contributed to our military’s success as America and its allies stood up for freedom against fascist aggressors.

America, after World War I, had taken a stand of isolationism, vowing to stay out of foreign wars and also halting its development of war planes. Our aeronautics industry continued to design and manufacture modern aircraft and was providing some of the most technologically advanced planes, but only for use in commercial flight. However, in 1939, in response to the rapid increase in the development of military war hardware by Germany and Japan, the U.S. Congress had approved a contest of sorts, challenging American aeronautics companies to design a badly needed, medium-range, armored bomber. This bomber would need the capabilities necessary to compete with the new fighter aircraft that had been developed by potential aggressors in the 20 years that had passed since WWI.

Almost every American aeronautics company took part in the contest,

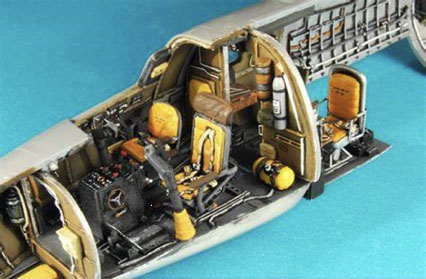

however it was the Glen L. Martin Company, today’s Lockheed Martin Corporation, that won it, along with the contract to manufacture 201 of the newly designed B-26 bombers. Peyton Magruder, a creative and skilled 26-year-old Naval Academy drop out, designed the B-26 and it became the most modern flying machine of its time. The B-26 was powerful with unprecedented armor and fighting ability. With the capability to carry 4000 pounds of bombs, it had two .50-caliber guns in a movable turret on top, a single .50-caliber gun in the Plexiglas nose, with another .30 or .50-caliber in the tail. During bomb runs, the bombardier would be positioned inside the Plexiglas nose which also housed yet another technological marvel, America’s newest secret weapon, the Norden bombsight. With a top speed of 315 miles per hour, to that date, the B-26 was the fastest bomber ever made.

In an earlier Cranford 86 profile we featured the life and career of Alan Okell. In early 1943 Alan was one of the first instructors to train new pilots on the B-26 Marauder. His story tells the grim history of the early days of this innovative new aircraft that was quickly nicknamed the “Widowmaker”. With its huge 2000 horsepower engines on unusually short stubby wings, formerly unheard-of landing speeds of 130 – 140 mph were required to prevent the B-26 from stalling and to allow it to land safely. During a 30-day period in 1942, while trying to figure out this overpowered aeronautic innovation, fifteen six-man crews were killed in training exercises. The saying “One a Day in Tampa Bay” was coined to describe this disastrous series of crashes which occurred at MacDill Airfield on Tampa Bay. For more details about the B-26’s early problems, see the Alan M. Okell profile at Cranford86.org.

The B-26 Marauder and the Norden bombsight had something in common. Initially they were both thought to be too difficult to master. Their failure to perform early on, was thought to be a fault of their designers and

both programs, at one point, were close to termination. Eventually, it was found that when a competent technician was in control and trained in the proper operational skills, that both the B-26 Marauder and the Norden bombsight were in fact, quite worthy of our country’s investment. We were able to find U.S. military training films from the early 1940’s that detail the fine skills required to operate each of these innovations (see YouTube links). The films highlight the importance of the role of instructors at the bombardier academy, as they patiently helped trainees to develop proficiency in these specialized skills. The security surrounding the Norden bombsight was elevated during World War II. In the event of an impending plane crash, crews had been ordered to eject the Norden device before ejecting themselves, in hopes that this would keep the Norden out of enemy hands. At war’s end these two creations were hailed as the finest offensive military weapons of their time and if they had not been part of our arsenal, the outcome of the war would have been much different.

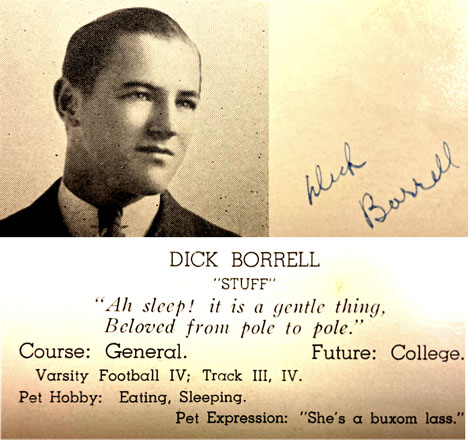

Richard, or Dick as he was known by everyone who knew him, was born in Chester, Pennsylvania in 1918. He moved to Albany, New York, before coming to Cranford in 1930, where he entered public school as a sixth grader. The family lived at 19 Grove Street at first, then 150 Elm Street and finally moved to 43 Orchard Street. They attended Trinity Episcopal Church on North Avenue. Dick was the youngest of his four siblings, Alfred the oldest, was 8 when Dick was born, followed by Marjorie who was 7, and Robert, 4. Their mom Florette was in charge of the WPA Sewing Project in Cranford, a Depression era program that gave work at minimum wages to women who would sew clothing for people in need. Their dad Alfred had become blind and could be seen walking around town led by a guide dog and using a cane. He died of heart failure while Dick was serving in the Army Air Force in January of 1942.

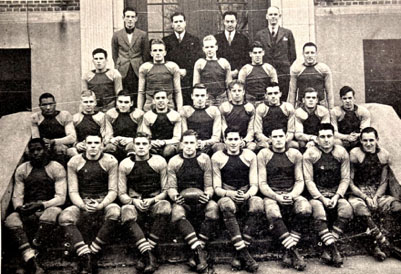

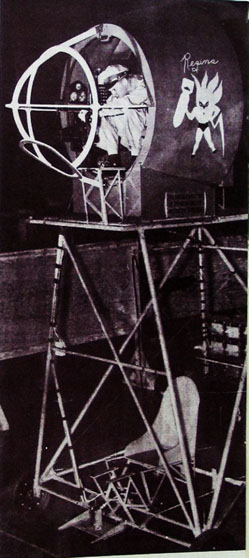

Dick played football and ran track while at Cranford High School. A Cranford Chronicle clipping from his senior year told of a fourth quarter, game-winning pass against Roselle, in which he was the successful receiver, truly a “glory days” moment. In his CHS senior yearbook he humorously listed his hobbies as “eating and sleeping”. After graduation in the class of 1937 he began working in Kearny at Western Electric, where his older brother Alfred was employed. According to records found by Stu Rosenthal, on October 16th, of 1940 at the age of 21, 5 foot 11, 165-pound, blue-eyed Richard Allen Borrell registered in the Army, about fourteen months prior to the attack at Pearl Harbor. His actual Borrell enlistment date was not until July 23rd of 1941 when he reported to Camp Davis in North Carolina. He was attached to the 96th Coastal Artillery for training in anti-aircraft gunnery. In late 1942 he enrolled into training to become a bombardier and was sent to Victorville, California in the Mojave Desert, outside of Los Angeles. In an eighteen-week training program, he was one of 105 cadets who would develop the skills needed to accurately drop bombs from high altitudes. The training involved complex mathematics using the E6B analog computer as well as the tactical skills needed to proficiently operate the Norden bombsight. Stu Rosenthal was able to locate Richard Borrell as a trainee in the Victorville Army Flying School (VAFS) Class 43-2 yearbook (43-2 denotes the year and month in which the class graduated). In it, Richard Borrell appears as a cadet. The book tells the story of the developmental journey of the bombardier’s training which began in the classroom, before advancing to initial hands-on exercises in an empty hangar, dropping sandbag bombs from wheeled scaffolds, similar to those that one might use for painting. Next would be mock bomb runs, dropping bomb-shaped flour sacks over the desert, with cameras monitoring their accuracy. What seemed impossible at first to the cadets was actually mastered by week eighteen and they were dropping bombs right on the mark. It was said that with the Norden, a good bombardier could put a bomb into a pickle barrel from 12,000 feet. Upon graduation from Victorville an enlisted cadet would be commissioned as an officer or a flight engineer.

As is typical in our research for some of our Cranford 86 stories, educated speculations are made in an attempt to fill in the blanks of our heroes’ timelines. With that in mind and the history now known about some other Cranford 86 heroes, some interesting possibilities have been discussed. After graduating from VAFS in February 1943 we lost track of our Hometown hero for 9 months. Some of our team members conjecture that he possibly could have been sent to another facility for specialized training, possibly to become familiar with the B-26 Marauder. Coincidentally, B-26

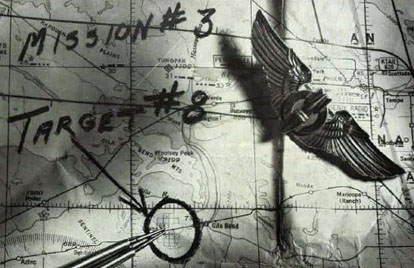

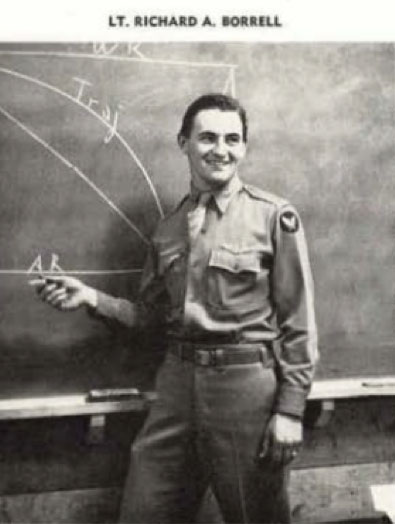

training was mostly happening at MacDill Airfield in Tampa, the same airfield at which our Alan Okell was serving when he was killed while training new pilots. Alan’s accident that took his life was in March of 1943. At that same time Cranford 86 Hometown Hero, Sergeant William Lee was also stationed at MacDill Airfield as well. Did our three Cranford Hometown Heroes cross paths during that period? No one will ever know; it is just the kind of thing that historians speculate as we put the pieces of a story together. What we do have proof of is that he returned to Victorville in November of 1943, one month prior to the birth of his baby girl Pamela. In the yearbook of the 44-3 class we found Dick now an instructor, pictured at a trajectory diagram with chalk in hand. The text near Dick’s photo stressed that the success of the bombardier came from their proficiency in the classroom and it referred to the expert teachings of the “Four Horsemen”, our Lieutenant Richard Borrell was hailed as one of those four. From the dates in this yearbook we have tried to create a timeline of Dick’s service from this point through the rest of his deployment. We surmise that the graduation of the 44-3 class, would be in February or March of 1944. Dick’s grave marker told us that he served in the 386th Bomb Group in the 555th Bomb Squadron, AKA the “Triple Nickel”, the 386th Bomb Group in the 555th Bomb Squadron, AKA the “Triple Nickel”, which was originally with the 8th Air Force and then transitioned to the 9th. In this case, history tells us that our military strategists were secretly building the elements of our armed forces for over two years leading up to the D-Day invasion. The mass training of bomber crews including thousands of bombardiers was just one of the pieces of this complex plan.

In discussion between Cranford 86 researchers and writers it was doubted that 2nd Lieutenant Richard Borrell, one of the most accomplished graduates of the VAFS academy, was “left on the bench” for one of the most pivotal days of WWII. However, as of this writing, we cannot confirm that he was with his unit, at Great Dunmow, 50 miles northeast of London on that fateful morning of June 6th, 1944.

An early morning briefing was called at 3:00 AM on D-Day, at Great Dunmow. The crews were informed that paratroopers and gliders had, hours before midnight, already dropped behind enemy lines. This news was met with cheers from the crews in attendance. The 386th along with 7 other bomber groups, would strike the western-most beaches in Normandy, code named Utah, precisely between 6:23 AM and 6:25 AM. Thousands of allied ships, many with flames erupting from their big guns, went on for as far as the eye could see. Eyewitness accounts from B-26 crew members described the rallying cries that broke out on board as darkness yielded to daylight and revealed the scene below. The mission of the eight B-26 bomber groups was to hit the Nazi big guns and machine gun nests that were perched above the beach along the Atlantic Wall. Starting in 1942, in anticipation of an allied forces attack, the Nazis used forced labor to construct this 1,670-mile cement wall to defend the shoreline.

The trip across the English Channel from Great Dunmow to Normandy was about 300 miles, it would take approximately 90 minutes by air. 424 newly modified B-26s headed out, each with a bombardier and a Norden bombsight, 290 of them would attack Utah Beach. We wonder, was our skilled bombardier instructor from Cranford, with an unknown number of his students, among the bombardiers in this group? The weather was bad, with rain, fog and low hanging cloud cover. This would force the medium bombers to attack from 2,500 to 3,500 feet, some even as low as 500 feet, a big difference from the more secure altitude of 12,000 feet which had been in the original plan. Despite conditions, the bombers were amazingly successful at hitting their targets and making hundreds of beach craters with 550 tons of precisely placed bombs. These craters would serve as foxholes for the US Fourth Infantry Division, whose amphibious landing was completed almost flawlessly. The bomber groups from Great Dunmow made two or three missions each on D-Day, completing various objectives along the Atlantic Wall as well as hitting inland targets. The high-flying B-17 and B-24 big bombers were unable to hit their planned targets due to the cloud cover. But, the nimble, speedy Marauders, flying below the clouds, were able to strike defensive guns, trainyards and bridges all which were critical military objectives, crucial for advancing German troops that were attempting to defend against the landing. The American losses at Utah Beach as compared to Omaha Beach were minimal. The B-26 Bombers were credited as being a key contribution to the Utah landing’s success. Only one bomber from the B-26 attacking groups was lost in the attack. The previously named “Widowmaker” was well on its way to being heralded as the safest, most successful plane of the WWII allied flying arsenal, with the lowest loss rate of any other WWII aircraft. Our research tells us that the 386th Bomber Group was also redirected to Caen on D-Day, which was the first objective of the allied forces as it was needed to start the march toward Paris. In all, an amazing 13,000 allied aircraft were part of the D-Day attack, it was the largest by three times of any aerial attack in history. It was said that the number of planes flying that morning, “blackened the sky”. The Cranford 86 group will continue to try and pinpoint the exact whereabouts of our Hometown Hero on D-Day. Refer to Richard Borrell’s story on Cranford86.org for updates. In order to try and gain an understanding of the relationship between a pilot and a bombardier, we were very fortunate to be able to interview a former B-26 pilot, 92-year-old Art Snyder, a member of the Cranford VFW. 1st Lieutenant Snyder flew 38 bomber missions in Korea in a B-26 Invader which was very similar to the plane flown by our Lieutenant Richard Borrell. Stu Rosenthal and I sat with Art on the porch of Art’s bayfront home in Brick, N.J., where we chatted for a few hours. Art explained that he had the same bombardier in almost every mission that he flew. While he and his navigator flew the plane to the bomb sight, Art said that it was the bombardier that took control of the plane during the “bomb run”. According to Art, the pilot would fly the plane with the bombardier behind him in the rear cockpit. The flight to the bombing destination would sometimes be hours long. Thirty minutes before reaching the target, the

bombardier would crawl on his belly through a small opening under the right side of the dashboard into the iconic glass nose of the bomber. To fit through the small opening, Art told us that the bombardier would need to remove his parachute. Once in place, with the target in sight, the bombardier would call out, “I got it”. At this point it was the bombardier that had control of the direction of the plane. Art said that all the pilot had to do now was keep the plane level and at a constant speed. The bombardier, in position and seemingly wrapped around the Norden bombsight, switched on the autopilot and entered the bomb type, ground speed, altitude, wind speed, and cross wind data. The computer would calculate all of the variables, exhibiting incredible accuracy from an average altitude of 10 thousand feet. Looking through the optical eyepiece, the bombardier would put the cross hairs precisely on the target and lock it in, by his control the Norden would drop the entire payload or as many bombs as desired. This whole process would take between one and five minutes. During that time of steady, level flying, the crew was at its most vulnerable to ground fire. Art shared that being surrounded by exploding “flak” during the bomb run, could make those moments feel like hours, being unable to take evasive actions to avoid danger. As soon as the bombs were dropped, the pilot took back the controls and hightailed it back to the base, grateful and relieved to be able to resume their evasive flying tactics. In numerous bombardier training films that our research found, the importance of this fleeting task was drilled into bombardier trainees. Thousands of man hours were spent to get them to that spot. At that moment, if the bombs were to go off course and miss the target, all the work and expense of designing and building these planes and bombs, the months of tedious training of the pilots and navigators, not to mention the risk of their lives, would all be for naught. So much investment had been made to put them at that moment in time, it was important for them to know that the success of the mission was all in their hands.

On the ground, the nemesis of allied air attackers was the Germans’ premier weapon of the era, the 88mm Flak anti-aircraft gun, or as it was called by some, the anti-everything gun. It too had been in development since WWI and by 1943 it had become the most feared weapon of the war to that point. With a vertical range of over 30,000 feet, when attached to an analog computer and radar it had the ability to fill the air around attacking bombers with 17 pound exploding shells that it could hurl at 20 rounds per minute, creating 1500 pieces of “flak” each. The shells did not need to hit the planes to be deadly, they had a barometric detonator that would explode at an altitude that the radar and computer would set automatically, and the flying, jagged metal would shred any aircraft within 200 yards. The saying “the flak was so thick; you could walk on it” was mentioned by Art Snyder as well as in several pilot interviews that we read during our research. In 1944, attacking fighters and the 88, as it was called by most, would be responsible for a loss rate of 714 killed or missing bomber crew members for every 1000, and an additional 175 wounded, an incredible casualty rate of 89%. Only 1 in 4 bomber crew members would live through the quota of 25 missions, which was raised to 35 by war’s end. Estimates said that the average life expectancy of an Air Force bomber crew member during this time was 12 missions. In 1944 alone, German defenses destroyed 6,400 allied aircraft and damaged another 27,000.

Immediately following the D-Day bombing campaign, the 386th would continue flying missions from England. Their ability with the well-trained bombardiers to accurately hit the German big guns, bridges, railroad yards airstrips, and V-1 rocket sites, was credited as key to the success of the allied advancing troops. They would support troops in multiple battles, the first being the battle for Caen, a German stronghold, predicted to be a relatively easy undertaking, it however, took two months of fierce fighting to control, ending in August 1944. The battle of St. Lo followed from July 7th through 19th and then the battle for the Falaise Pocket from August 12th through the 21st. These towns were all within a 30-mile radius, which gives a sense of the intense resistance of the Nazi forces. In September, the 386th would also

support the battle to capture the port of Brest in Brittany, France.

Even though it was hundreds of miles south of Normandy, controlling

this port was deemed as essential, as multiple ports were needed to

supply the tons of provisions that an invading army would need each

day. Each mission was fiercely defended by the deadly 88s as most of

the targets were inland and guarded by the entrenched Nazis who

had occupied France since July 1940.

After the Liberation of Paris in August of 1944, the 386th relocated its home base to Beaumont-sur-Oise, on October 2nd, 1944, 20 miles northwest of the French capital. From here the B-26 squadrons would use their accurate bombing tactics to support the Allies on their march to Berlin. It is here, while supporting General Patton’s Third Army at the fierce battle of Metz (September 27 to December 13), that we believe our Lieutenant Richard Borrell at the age of 25, met his fate while on board his B-26 Marauder. A MACR (Missing Air Crew

Report) found by Stu Rosenthal told us that a B-26 from the 555-bomber squadron, Dick’s unit, had crashed on October 13, 1944, while on a mission to destroy a railroad bridge in Dillingen, Germany, 554 miles away. As this coincided with the date of his death, we assume that Lieutenant Borrell was on that same mission, executing the tasks for which he was so highly skilled at performing. His family believed his plane fell victim to flak shrapnel. The fact that there was a grave, told us that he was not lost over enemy territory as was the fate of most crew members whose planes were shot down. The ability of a B-26 to keep flying while badly damaged was one of the attributes that made it the legendary fighter that it was. Severely damaged, limping Marauders regularly performed “wheels up landings” on the belly of the aircraft with a high percentage of success. We believe that his crew was able to bring

Dick back to Beaumont-sur-Oise. He was buried in France at the

Epinal American Cemetery alongside the Moselle River at Dinozé and remains there to this day. Dick Borrell left a wife, Christine and an infant daughter, Pamela in Needles, California, and his mom Florette and sister Marjorie Moore in Albany, NY. Also surviving him were two brothers, Robert, a Corporal and aerial photographer in the Marine Corps in the South Pacific and Alfred Jr. in Haddonfield, NJ. Our efforts to contact his daughter Pamela, who we presume to be about age 76, have been unsuccessful up to this point. We did locate Dick’s nephew, Alfred III still living in New Jersey. He provided a photo of his uncle in an open cockpit training plane, although he was not able to provide any personal information about his uncle. Our search for more details will continue, hopefully to be included in Cranford 86’s tribute book Volume #4. Lieutenant Richard Borrell was one of 40,000 bombardiers who served in the American Army Air Force in the four years of our involvement in WWII. His bravery and skills were multiplied exponentially as he trained his students to play critical roles during a pivotal segment of our country’s stand against fascism. His actions as well as theirs may have changed the outcome of the battles that were instrumental in our victory. If we had been defeated, America as we know it would not exist. He is a member of our Cranford 86; a true American patriot and we owe him a huge debt of gratitude.

If you have been enjoying our Cranford 86 profiles, we would love to hear from you. Email us at info@cranford86.org. The Cranford 86 stories are now part of the new Cranford Historical Society’s website at cranfordhistoricalsociety.org and our books are available there for purchase. We would like to thank the Cranford PBA Local #52 for sponsoring Lieutenant Borrell’s banner. It will be dedicated after the 100th Cranford Memorial Day parade when Richard Borrell will be recognized along with the other Cranford 86 Hometown Heroes of 2021.

Use these links to access more information about the Norden bombsight and the B-26 Marauder bomber.

1944 Army Air Force training film for the operation of the Norden bombsight in the classroom.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=143vi97a4tY

1944 Army Air Force training film on operating the Norden bombsight on the ground.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rbtmb_JrX2g

1944 Army Air Force training film on operation the Norden bombsight in the air.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MIE_XXmGUg

1944 Army Air Force training film for piloting the B-26 Marauder Bomber.

https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&ei=YNjgX6iLPK-r5NoP3dml4As&q=how+to+fly+the+B-

26+bomber&oq=how+to+fly+the+B-

26+bomber&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQAzIICCEQFhAdEB46DgguELEDEMcBEKMCEJMCOggIABCxAxCDAToLCC4QsQMQxwEQowI6DgguELE DEIMBEMcBEKMCOgIILjoICC4QsQMQgwE6AggAOgUIABDJAzoFCC4QsQM6BQgAELEDOggIABCxAxDJAzoLCC4QsQMQyQMQkwI6CwgAE LEDEIMBEMkDOgYIABAWEB5Qiw5Y005g71JoAHAAeACAAV6IAYIPkgECMjaYAQCgAQGqAQdnd3Mtd2l6&sclient=psy-

ab&ved=0ahUKEwiou7ftyd_tAhWvFVkFHd1sCbwQ4dUDCAk&uact=5#kpvalbx=_bNjgX7YBqK7k2g_ljrGoCQ9

The article that was used for much of the detail of the 386th’s participation on D-Day.

https://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/mission-utah-beach-180972310/#:~:text=On%20June%206%2C%201944%2C%20300,low%2Dlevel%20and%20on%20time.