Seaman First Class Friend Joaquim (although he always used Joseph) Burton

Tin Can Sailor, Seaman First Class Friend Burton. One of Cranford’s 86.

By Don Sweeney, research by Stu Rosenthal, military guidance by Vic Bary,

Proofreading by Janet Ashnault

Present day photo of Friend’s uniform cap. The cap has been offered to The Cranford 86 Project by Dr. Friend Burton. We hope to have it displayed as part of the Memorial Day ceremony in which Friend’s banner will be dedicated.

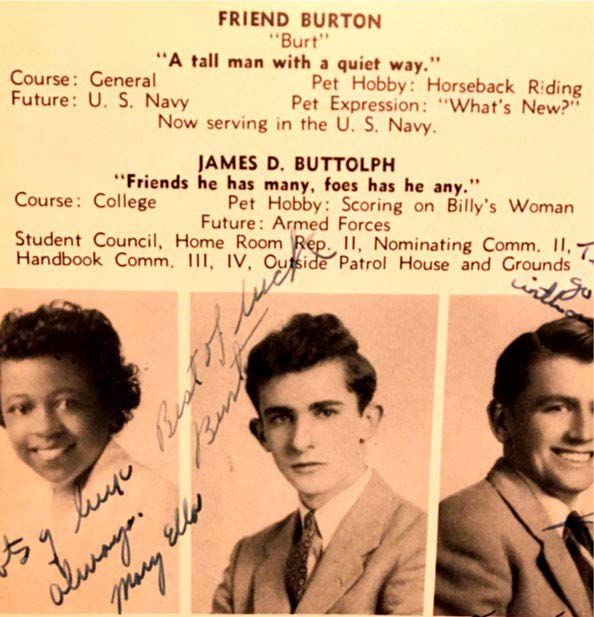

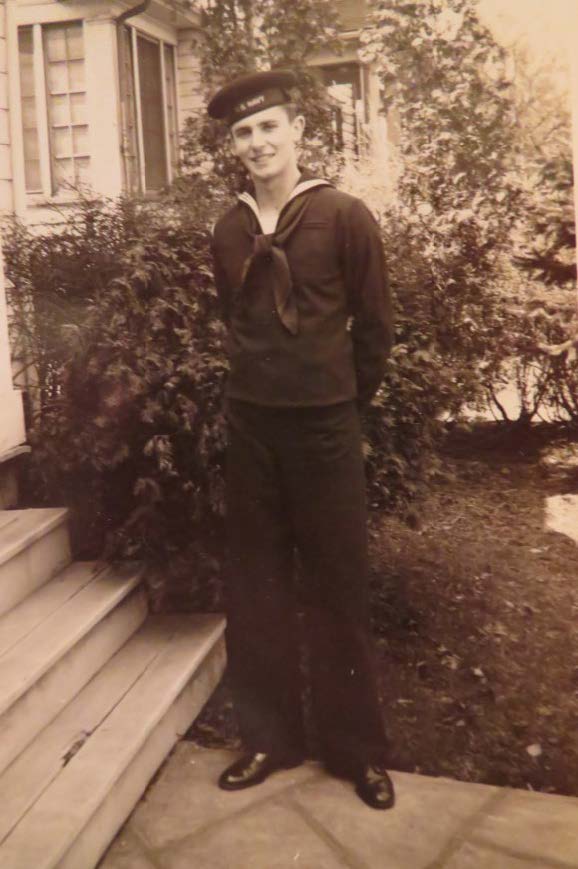

The news of the December 7th, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor stunned every American. One could only imagine how a young junior at Cranford High School would have reacted to the headlines, and that is how our story begins. Many high school juniors and seniors that were planning for college or considering life’s other options during this fateful time, suddenly opted for military service as a career choice. It would seem that this is what happened with seventeen year old Friend Burton of 29 Elizabeth Avenue in Cranford. While still in high school, he would enlist in the US Navy in December, and be sent to Rhode Island for basic training in February of his senior year. He was able to return to Cranford in June to sign yearbooks and receive his diploma with the class of 1943, before once again shipping out to serve our country in its time of need.

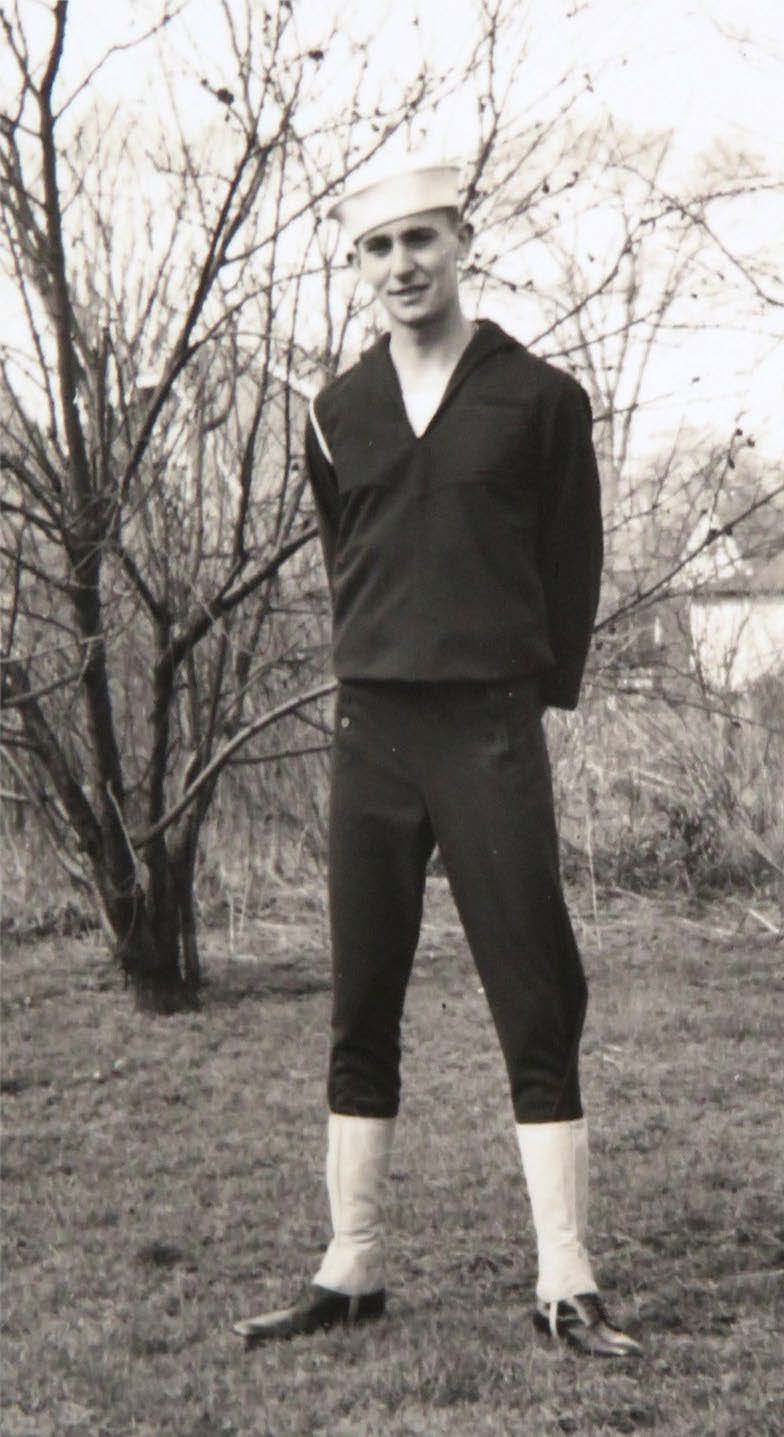

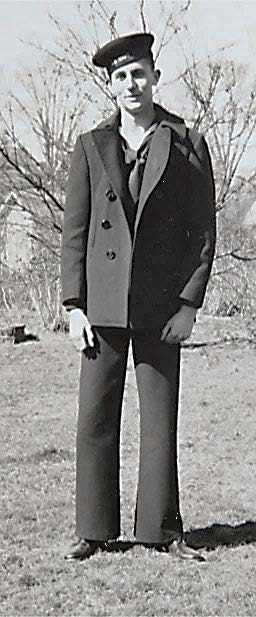

“ A tall man with a quiet way”, Seaman First-Class Friend

J. Burton in his “undress blues” and the traditional s ailor cap (see photo of Friend’s cap at Cranford86.org)

After advanced training in Boston, Friend was assigned to the newly commissioned USS Braine DD-630, a Fletcher Class destroyer named in honor of Rear Admiral Daniel L. Braine, a Civil War Naval hero from Brooklyn, NY. Being a member of her inaugural crew, this designated Friend to be what is known as a “plank owner” of the Braine. After a cruise to Maine to test out the mechanics of the new vessel, the Braine was ordered to the Pacific theater in early August of 1943. Heading south around Cape Hatteras they encountered a violent hurricane, that over the course of two days, nearly capsized the ship. It was a baptism by fire for the new sailors. Needing repairs after the storm, they stopped in Trinidad before passing through the Panama Canal. The Braine continued north to San Francisco before being assigned to be part of a task group escorting troop ships to Pearl Harbor. When they arrived there, the reality of war must have surely hit home, as the crew stood on deck at attention, in stunned silence as they passed the sunken remains of the USS Arizona.

In Pearl Harbor, five battleships had been sunk or badly damaged along with three cruisers, three destroyers and numerous smaller vessels. Luckily, none of the three Pacific aircraft carriers were at port that morning. The blind-sided attack awakened a sleeping giant and U.S. manufacturing went into high gear and amazed the world with its preparations for retaliation. From 1941 to 1944, The United States would launch 24 battleships, 36 aircraft carriers, and an incredible 178 destroyers. Battleships and aircraft carriers had crews numbering close to 2000 and each destroyer was manned by approximately 300. To man these ships alone, more than 200,000 sailors would be needed, and many more as well in total, in order to wage war against the Japanese Imperial Navy. Not only were the ships fully manned, most were overcrowded. America’s youth had heard the call to service and answered it.

Friend (center)on leave in Australia with time for a fun picture in the brig with two shipmates

Originally known as a torpedo boat destroyer, the destroyer was first designed by the Spanish Navy and created to combat torpedo armed submarines. Destroyers evolved through the 20th century to defend naval task groups, namely aircraft carriers, battleships and cruisers. They were built with relatively thin metal skin which made them lightweight, fast and maneuverable. Because of their light weight, they sat very high in the water, making them hard to be hit with torpedoes. This thin skin,however, made destroyers very vulnerable when they were hit, adding an extra degree of danger for those who served on this type of vessel. Equipped with depth charges, torpedoes, and anti-aircraft guns as well as lethal cannons, destroyers were able to provide defense against submarines, as well as other torpedo carrying offensive attackers, including torpedoes launched from aircraft. Their thin skin is what gave the destroyer the nickname of “Tin Can”, and its crew members were called “Tin Can Sailors”. It was said by sailors that, if being on a battleship or carrier was like living in a big city, being on a destroyer was like living in a small town. Everyone knew each other and there was a brotherhood between its men.

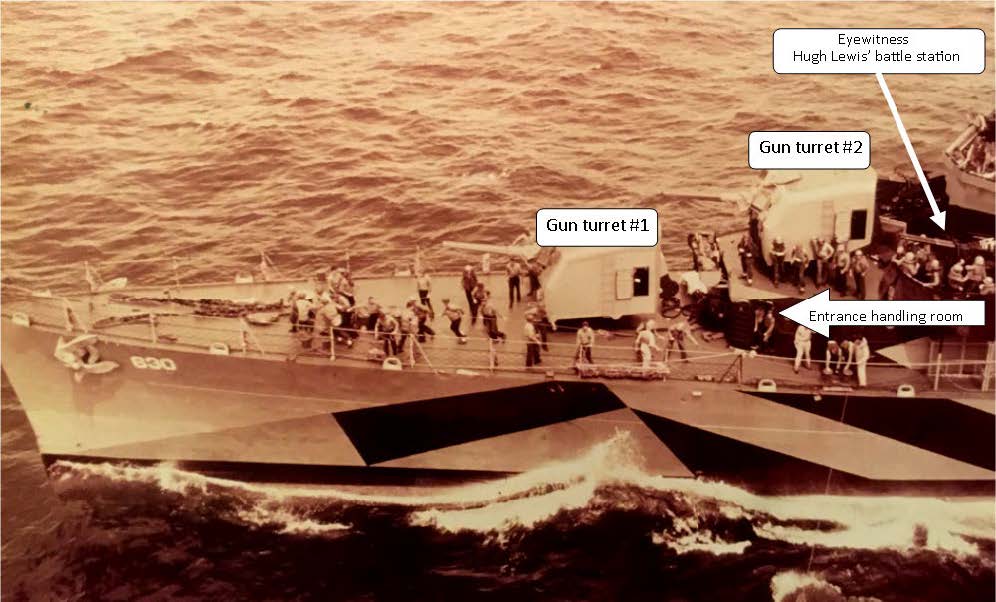

Cranford 86 researcher Stu Rosenthal located Friend’s nephew, Nick Falzarano, living in Union. Nick shared with us an interview that he had done in 1991 with Hugh Lewis, a handling room attendant who had served with his uncle on the Braine. This information gave us a feel for what day to day life was like aboard a destroyer. When the crew was called to general quarters, or battle stations, everyone immediately manned the specific job that they were there to perform. Seaman First Class Burton was assigned to the “handling room” for gun #2. This 10-foot square room was beneath the deck that supported the gun turret. In it, three men would provide the munitions to the long-range, 5-inch cannons. One would place the 58-pound shell on a conveyor that would lift it to the gunners. The powder cans that served to propel the shells were 5 inches in diameter and 40 inches long. These were handed up through a hole in the deck by the second man. The third man wore headphones and was in communication with the gunners. He would manage the operation and provide backup if needed. As a Seaman First Class, when not at general quarters, Friend Burton would also have been assigned many mundane, but essential tasks, from kitchen help to daily cleaning and ship maintenance.

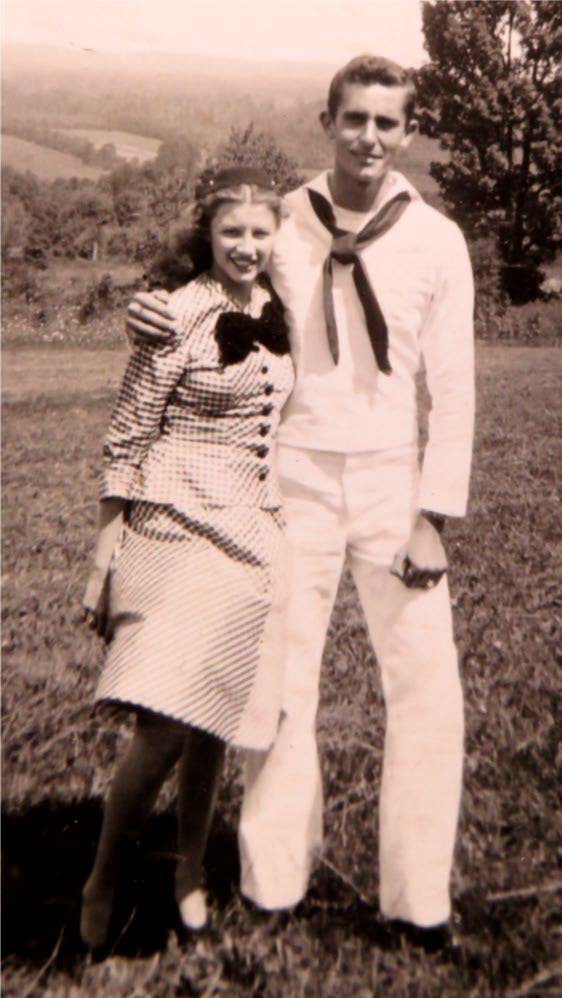

Friend Burton in his dress whites, with sister Mary. Friend was able to get home for R&R in the summer of ’44 while his ship was in California for repairs.

The Allied forces employed an “island hopping” strategy, bypassing many Japanese occupied islands, and selecting atolls and islands that held resources critical to the war effort. Many times, these islands contained an airfield that was launching attacks against Allied forces. Sometimes an island was targeted because it had the location and geographic characteristics suitable to building new airfields. While aircraft carriers offered a home for fighter planes, land-based airstrips were needed to accommodate large bombers and transport planes.

From Australia to the Philippines, the Marianas and Solomon Islands, the USS Braine had a long list of violent encounters in its two years of action in the South Pacific, and Friend Burton was a part of each one. A few of the battles are highlighted below. Visit Cranford86.org for the Braine’s entire chronological list of encounters.

On June 14th, 1944 the Braine participated in a shore bombardment of Tinian in the Mariana Islands. While the enemy was silenced, during the encounter the Braine was hit by a 4.7-inch shell causing 20 casualties, 3 of whom were killed in action. The following day she broke off from the battleship group and was ordered to Guam and then back to Pearl Harbor via the Eniwetok Atoll for repairs from damage received in the attack. (see Paul Sjursen’s story on Cranford86.org) A pleasant surprise came when repairs could not be completed in Hawaii, and the Braine was ordered to San Pedro, California for a month in dry dock. It was during this period that Friend returned to Cranford for R&R.

On August 21st, 1944 the Braine headed back to Pearl Harbor as an escort for the battleship South Dakota. From there her fight card continued, the Philippines, Manus Islands, New Guinea, Leyte and Palau. While escorting troop transport ships to Minduro, in the Philippines on December 15th, 1944 she encountered her first suicide plane. The crew was successful in repulsing the attack and the “flying bomb” fell 200 yards short of the ship’s fantail. The first recorded kamikaze attack in WWII was on October 13th, 1944 and they began to occur with escalating frequency thereafter. Zealot pilots were sacrificing their lives for the emperor, who they believed to be a supreme being. Defending our ships in the South Pacific from these suicide dive bombers became a new priority and new defense protocols would need to be created. (see the stories of James Roberts and Howard Goodman at Cranford86.org)

A small portion (about 10%) of the Braine crew shown reporting to the aft deck for their shift. Each enlisted man worked 4 hours on 8 hours off. Note the bell-bottomed working uniforms known as “dungarees” which existed in the Navy from 1913 to 1999.

On the moonless night of January 7th, 1945, while serving with two other destroyers, the Braine’s radar system detected an enemy vessel about 60 miles west of Manila. An incendiary flare was fired that illuminated the ship in the distance and it was identified as a Japanese destroyer. The enemy ship was shelled and “sent to the bottom”.

In May, the Braine was ordered to join Destroyer Squadron 51 off Okinawa, the smallest and least populated of the five main islands of Japan. Its successful capture would give the allies the airbases needed to attack the mainland of Japan. The Battle of Okinawa would become one of the longest battles in history, with Allied forces in a ferocious clash against fanatical warriors who were known for their fight to the death mentality, now amplified by the fact that they were defending their home soil.

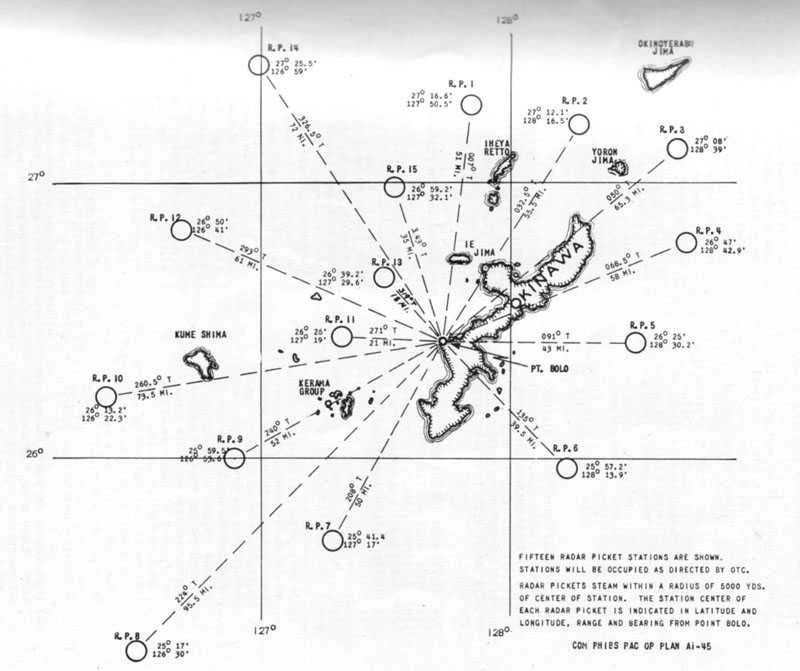

A new defensive tactic to protect the fleet from the suicide bombers was now in place. It was called Radar Pickets, and was first fully implemented at the battle of Okinawa. Similar to a picket fence, fifteen radar stations were set up surrounding the island. Each station was to have two or more destroyers equipped with new high-tech electronics, several LCS, swift landing crafts (known as mighty midgets, pallbearers or little boys) and two Corsair or P-47 fighter planes above.

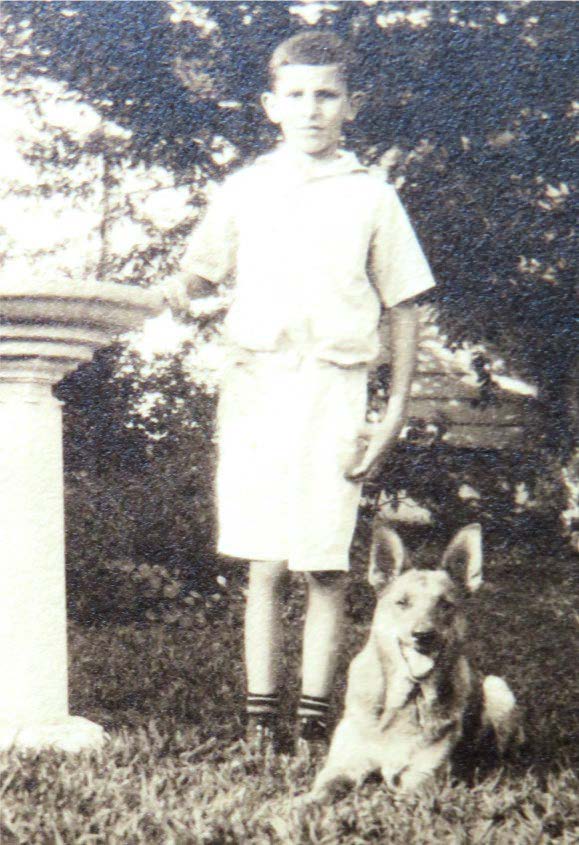

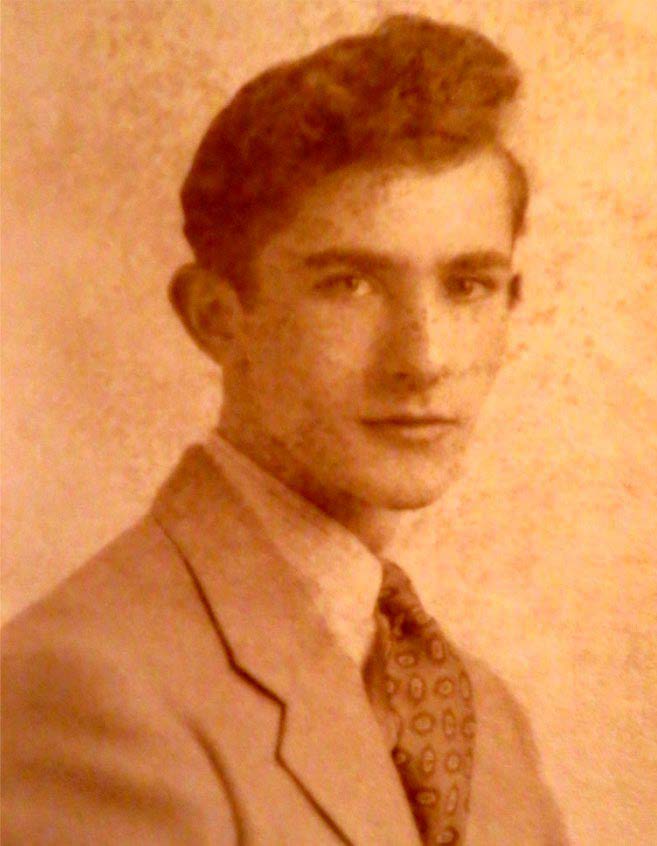

Young Friend Burton with his dog. His family said he was named after a Dr. Friend. We could not confirm the relationship with the family. The Brooklyn based family moved to Cranford 4 years after Friend’s birth in 1925 or 1926.

On May 25th the Braine and its crew of 325 along with the USS Anthony relieved the USS Bennion at Radar Picket Station 5. The Bennion and its companion destroyer had shot down four kamikaze attackers the night before. On the 26th the Braine and the Anthony both shot down attacking planes and more attacks were expected.

The following accounts are a mixture of facts from the second by second declassified report written by the Braine’s commanding officer, Captain W.W. Fitts, and a variety of eyewitness interviews that were published by the Navy. Some segments are from Nick Falzarano’s interview with Hugh Lewis. Many of the accounts are graphic and may be hard to read by some.

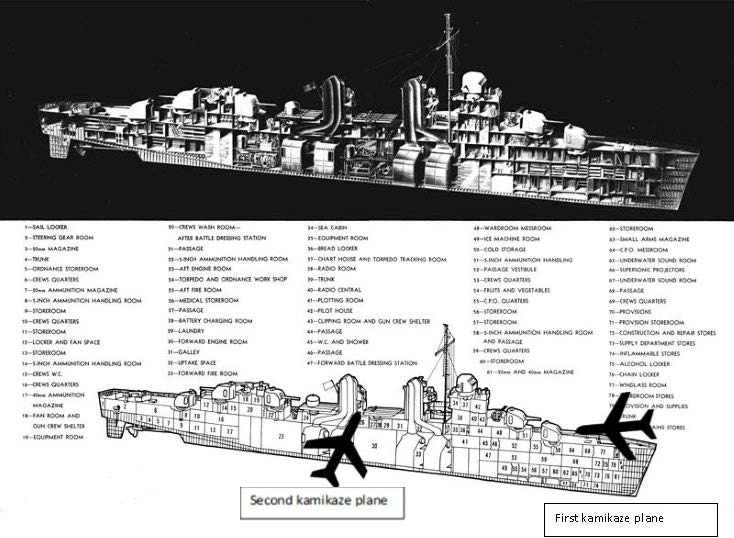

On the morning of May 27th at 6:00 AM, the two Corsair patrol planes returned to base due to extremely poor visibility. At 7:30 AM three unidentified planes were spotted 25 miles away on radar. General quarters were called. At 7:34 AM a plane, identified as an Aichi D3A (known to the allies as a “Val”), dropped from a low hanging cloud 3 miles away. It approached the Anthony, which was about 1000 yards from the Braine. Both destroyers were cruising in tandem at 20 knots. All guns on both ships were targeting the Val and it was fired upon. Flames and smoke came from the plane as it was hit. Even while flaming, the suicide pilot guided the plane, strafing above the waves and striking the Braine. The Val came down straight across the bow and into gun turret #1, shearing its wings off and plowing directly into handling room #2, where Friend Burton was manning his battle station position. A 500-pound bomb on a delayed timer exploded 30 seconds after impact which set the Braine ablaze. Hugh Lewis, from his position on an anti-aircraft 40mm gun just above gun turret #2, saw the plane coming when it was 30 feet away and was able to avoid the impact and explosion. His accounts describe seeing the pilot in the cockpit seemingly already dead as he finished his mission. Hugh described the plane as a very old, canvas stretched WW1 style plane, conflicting with official reports that it was a Val.

Next to dad’s 1937 Chevy. A very popular sedan of the era. Friend and sister Mary have a little winter fun in front of 29 Elizabeth Avenue.

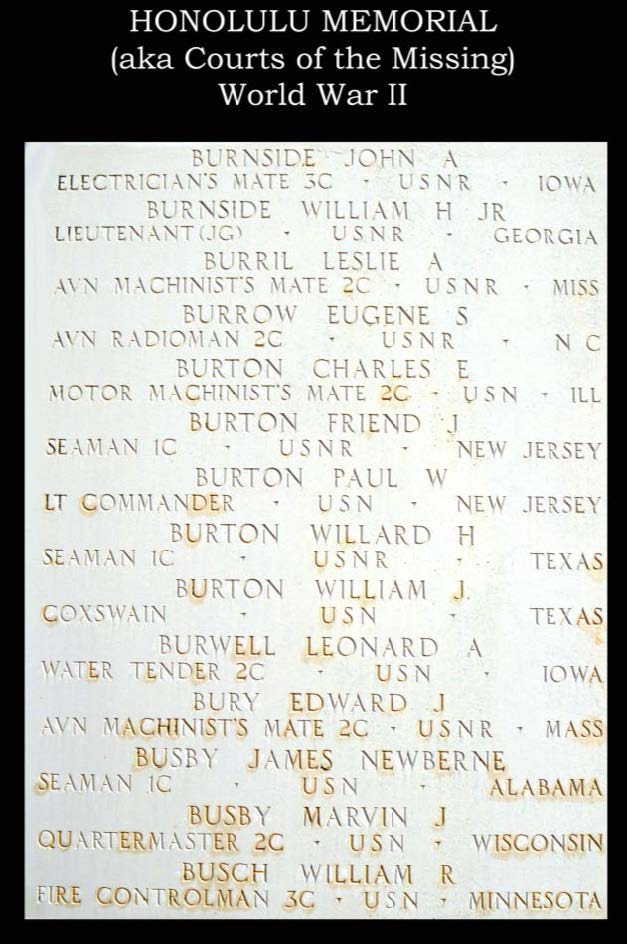

Within a minute, another plane hit, carrying another 500-pound bomb. It was described as being even worse, if that could be possible. A huge smokestack was knocked right off the ship into the ocean. Utter horror ensued, many crew members were thrown overboard, and it seemed that everything was on fire. Only one small hose was available to fight the raging inferno. Captain Fitts, in a last second attempt to avoid the approaching plane, had called for full right rudder at flank speed. With the command center completely destroyed the full throttle and rudder position could not be altered. This caused the 376-foot ship to swing around in a clumsy, violent loop in the water. The captain ordered an abandon ship. The wounded started to be lowered into the water with buoyancy devices accompanied by healthy shipmates. To make the situation worse, the erratic circular actions of the ship became an imminent danger to the floating sailors. Eyewitnesses said the water had turned red and this attracted yet new attackers in the form of sharks. Sailors on board were using rifles and anti-aircraft guns to kill the attacking sharks before they could reach their shipmates. Some said that in this incident, more sailors were killed by sharks than by the Japanese. It took an hour to bring the ship under control, and another for the Anthony and the LCS’s to extinguish the fires. By noon, 40 men who went into the ocean were classified as missing, Cranford’s Friend J. Burton was among them. In all, 67 men were classified as killed in action and over 100 wounded, all within two minutes. It was the highest casualty rate of any destroyer in the war that did not sink. The crew of the USS Anthony filmed much of the episode, from the kamikaze strike to the firefighting assistance that it and LCS 86 had provided. See that film at Cranford86.org. Many Silver and Bronze Stars were awarded by President Truman to crew members of the USS Anthony and the crew of LCS 86, as well as numerous other commendations for both rescuing crafts and their crews.

A small panel from the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu where 18,095 names are engraved of the brave men that were lost and whose bodies were never recovered.

https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/americas/honolulu-memorial

On June 22nd, 1945, after a grueling 2 months and 3 weeks, the Allied forces were victorious in capturing Okinawa. Heavy losses made this a bittersweet victory. By the battle’s end, incredulously, 36 ships were sunk, 12 of them destroyers. The Americans bore over 49,000 casualties including 12,520 killed. It was planned that Okinawa’s Kadena Air Base would be the launching point of the air invasion on mainland Japan. That attack would never happen.

After three weeks of preliminary repair, the USS Braine was ordered home for a complete overhaul. On August 6th, 1945, two years to the day from her departure, she arrived back in Boston Harbor. On the same day, halfway around the world, an earthshaking event was taking place. The first atomic bomb was being dropped on Hiroshima, followed two days later by another at Nagasaki. A few days after that, on August 14th, the war was over.

After two years of dedicated service in the South Pacific that contributed to the victory of the Allied forces, Seaman First Class Friend Joseph Burton died and was lost at sea at the young age of 20. At home in Cranford, a high mass was offered for him at St. Michael’s Church where he had been an altar boy and also attended school. He left a grieving family behind which included his mom and dad, John and Brenda Burton, as well as a sister Mary, age 27 and a brother Kenneth age 36.

This “tall man with a quiet way” as quoted from his high school yearbook, bravely stepped out of the normality of life as a high school student to serve our country when it was needed most. There should be no question why he and his comrades are referred to as the Greatest Generation, in answering the call of duty, they altered history and basically saved the world from tyranny. Friend J. Burton was an American patriot, one of our Cranford 86, and has earned our undying gratitude.

He was known to his friends as Burt and that’s how he signed his photo in the “Golden C”. Although Friend started his high school life at St. Benedict’s in Newark he finished it at Cranford HS and graduated with the Class of ’43. In answer the yearbook query of “Future:”, more than 50% of the young men in this class responded Service, Army, Navy or Air Corps.

The husband of Kenneth Burton’s daughter Catherine, Nick Falzarano, had been inspired to research the history of his wife’s uncle, our WWII hero. Nick’s additions to our story were priceless. Kenneth Burton named his oldest son Friend in honor of his brother. We located Dr. Friend Burton, age 71, a psychotherapist in New York. He shared with us the contents of a box of artifacts that were returned to the family after his uncle’s death. We are very grateful that the Burtons have plans to join us on Memorial Day for the dedication of their uncle’s banner.

Special thanks to Dan DeWeever, a resident of Elizabeth Avenue. Not only did the DeWeever family sponsor the banner of the serviceman that played on the same street as their children, but Dan also performed expert research uncovering the narrated 16mm movie that was filmed from the USS Anthony. That was a real find and an invaluable addition to our story.

For this story we were blessed with an amazing selection of pictures, movies and artifacts from Friend’s two years on the USS Braine. Visit Cranford86.org to see them all. If you have any information about any of our Cranford 86 or would like to sponsor a hero that may have a connection to please contact us at info@cranford86.org.

Kamikaze video and the story of WW2 working up to Okinawa.

46-minute narrated film by The Captain of the USS Anthony. It contains the actual kamikaze strike of the USS Braine

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E8705iJPapc

Friend Burton, one of Americas Greatest Generation. He had the courage and character to voluntarily step up to the unimaginable experience of fighting in a World War. We can only imagine what life may have had in store for him, had he survived the attack on his ship on the morning of May 27th, 1945?

A diagram of the new radar picket protection system of the fleet working off Okinawa. According to date we found 36 ships were sunk, 12 of them destroyers. In addition, 763 aircraft were lost, and 12,500 men were killed or drowned during the eleven weeklong between Easter Sunday April 1st and June 22nd, 1945. The kamikaze tactics of the desperate Japanese forces were at their highest intensity, not only with dive bomb attacks, but by suicide boats and submarines as well.

USS Braine DD-630 underway with her crew in action. This photo shows the area where the first kamikaze plane came across the bow and struck handling room #2. Take note of the vantage point that Hugh Lewis had from the 40mm anti-aircraft gun that he was manning.

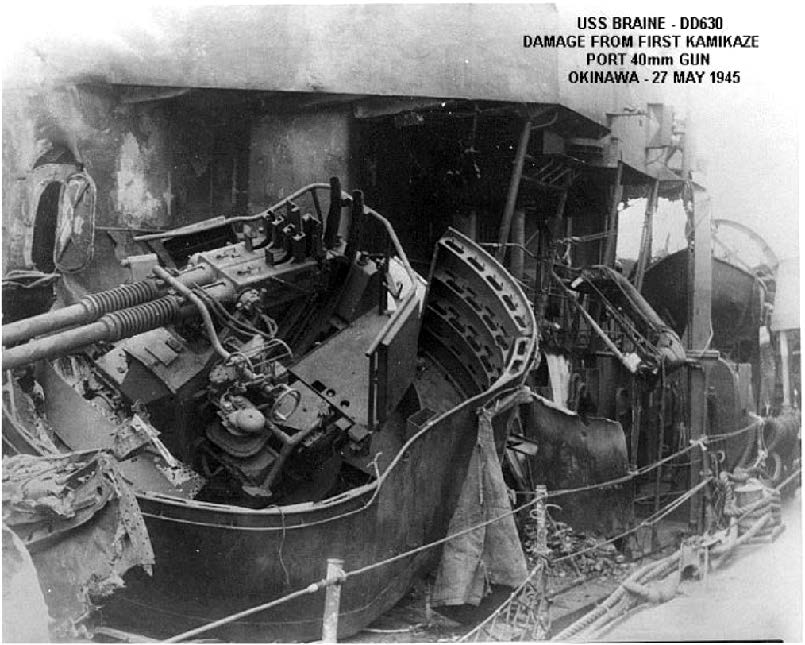

Official Navy damage report photograph: The port 40mm anti-aircraft gun that Hugh Lewis was manning at the time of the attack that took Friend Burton’s life. After seeing the approaching kamikaze plane, he fled his position, tripped on a wire that landed him safely between 2 steel walls that saved his life.

The USS-Braine DD-330 as it looked in 1943 entering the Pacific theater. Take note of how crowded a

376-foot ship looks with 325 sailors on board.

Friend in front of his home at 29 Elizabeth Avenue while on leave in the summer of 1944

Present day photo of Friend’s cap, it was part of the personal effects that were returned to the family after his death.

A 48-star American flag that was part of Friend’s personal effects, it is marked “Mare Island 1942”.

(see inset) This was the San Francisco naval shipyard that the Braine stopped at on its first voyage. From the look o f it, it was may have flown on the Braine through many of the battles that happened in the two years at sea. We were unable to confirm situation that caused it to be given to the family of Friend Burton after his death. If only a flag could talk. This one has some stories to tell.

USS Braine, official Navy damage report photo. During the attack, Friend Burton was at his battle station in the handling room under the gun turret.

Friend, in his peacoat and the hat.