Westfield Hall of Fame 2022 Inductee:

Samuel Downer, Sr. – “Westfield’s Greatest Revolutionary War Hero”

Submitted by Julian Hershey

The Westfield Hall of Fame this year welcomes Samuel Downer Sr., an 18th century blacksmith and patriot who with his hammer and fire helped give shape to American history.

Endowed with great physical stature, vitality and good health, Mr. Downer Sr. lived for nearly 102 years. His enterprising nature and boundless energy helped mold early Westfield’s cultural, spiritual and commercial life. In addition to his forge, he started a general store in Westfield, was a tavern proprietor and helped defend his community and country in war.

No history of Westfield is complete without a nod to Mr. Downer, and to his son, Samuel Downer Jr., whose own achievements in business and service to the community, large as they were, were perhaps a logical progression from those earlier efforts by his father.

Samuel Downer Sr. was born in 1723 in Norwich, Conn. He moved to New Jersey while still in his youth, as many from Connecticut did in those times, in search of land and a better life. He found both, first in Elizabethtown, then in the West Fields of Elizabeth. He served as a blacksmith’s apprentice, learning the trade of his father before him, and is described in the “Downers of America,” a genealogical history, as “having been of a genial temperament.”

Sam married Hannah Potter of Elizabethtown, with whom he started a family and moved to West Fields in the mid 1740s. The Downers were early members of the Presbyterian Church, and for years their home at Mountain Avenue and East Broad Street was both physically and symbolically at the center of the town. The general store he started and, across the street, the tavern in which he became a partner, helped form a hub for the village. And each business seemed to involve the son as much as the father, if early histories are to be believed. Where one’s handiwork started and the other’s ended is a detail obscured by the passage of time.

Meanwhile, some 50 years of Sam’s life still lay ahead—as did the Revolutionary War.

While proofs in the form of documentary evidence are again scarce, information gleaned from various sources supports our view of Sam Sr. as a patriot, a community figure active in the service of his country, a nation struggling to be born. The picture emerges of a West Fields man who played different roles at different times: a private in the militia; a wagon driver carting supplies; and an innkeeper who hosted General Washington himself at the family’s tavern.

Broadly speaking, such details are informed by, but also constrained by, what can be found in primary-source documents. The Daughters of the American Revolution, a group well known for its thoroughness in historical research, has found documents that show Sam was paid for carting services during the war, presumably by the Continental Army or militia.

Other official records suggest there is much more to the story. While in 1775, the year the war broke out, Sam Sr. was too old and Sam Jr. too young to serve, both joined the militia the next year—the father as a private, the son as a drummer boy.

Both names appear in what many consider the leading record of service by Jersey men in the war, the “Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War,” published in 1872 by state Adjutant General William S. Stryker.

Sam Sr.’s short entry says only “First Regiment, Middlesex; also State troops.” But Downer family records go further, stating he enlisted on Feb. 12, 1776, as a private in a unit of Minute Men led by Col. Nathaniel Heard. The Minute Men were the most fit and most committed in the militia. Sam Sr. would have been twice the age of many men in the unit, but perhaps the former blacksmith’s physical strength and fortitude quieted any concerns about his age.

Another challenge in piecing together this story is that he apparently did not enlist in the county in which he lived, Essex County—the county to which West Fields belonged at that time, and where Sam Jr. enlisted. Militia units, though the rules were seldom strictly observed, were supposed to draw on men from the counties in which they lived.

But efforts at military organization, particularly at the start of the war, were chaotic. Authorities on the subject say militiamen changed companies constantly. William Stryker himself wrote, “They were often in one Co. today and assigned to another tomorrow,” in a letter that is part of the research library of the New Jersey Historical Society.

Does it really matter whether Sam Sr. enlisted in Middlesex County or Essex? Both bordered Staten Island, which in years to come would be a hornet’s nest of British and Hessian activity. Indeed, commencing with the British invasion in the summer of 1776 and after the loss of New York City to the British that fall, New Jersey citizens and militia were forced for several years to fight on multiple occasions for their families, their livelihoods, homes and towns. No one asks where you enlisted when you are defending your neighbor’s or your own home.

Mr. Downer Sr. saw his house and forge burned in the famous pillaging of Westfield by the British in 1777. There are records proving that. The family genealogy goes on to say that all through this period, father and son “were called upon for service as emergency required.” And those emergencies were many. Conflicts included such major battles as the Battle of the Short Hills, Connecticut Farms and Springfield. At Springfield, the family records say, “the elder Samuel became separated from his company during the engagement, owing to the irregular manner of fighting, and tor a time was in a position of great danger between the fires.”

In closing, perhaps it is right for published histories of Westfield to pay their respects to Samuel Downer Sr., as most do, with broad strokes rather than attempting to tell his story more completely. It seems impossible to do more without approaching fiction and risking invention.

But we do lose something by not remembering people like Sam Sr. more fully. We recall that he lived until 1824, and in good health, his family says. This would have made him, in his time, one of the oldest living survivors of the Revolutionary War. In his later years, one account says, he became known around Westfield as a constant teller of stories about the war and his part in it. What a loss that no one wrote them down, even if that’s all they were—stories.

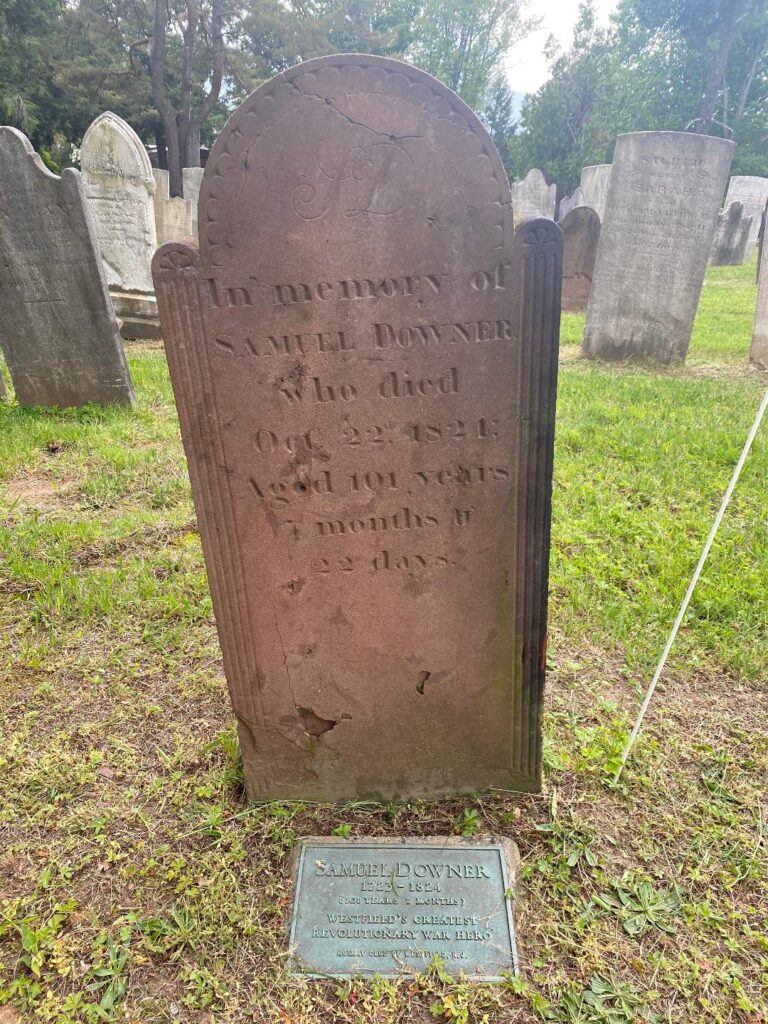

Sam’s part in the war and, more broadly, our town’s history, would seem at risk of being obscured completely were it not for a small bronze plaque that lies atop his grave in the Presbyterian Church Cemetery. One can choose to believe, or not to believe, what it states on the plaque: that Samuel Downer Sr. was “Westfield’s Greatest Revolutionary War Hero.”

The Westfield Hall of Fame is a Committee of the Westfield Historical Society which has named nine inductees for the 2022 Hall of Fame Class. In addition to Samuel Downer Sr., they are Clara Bolger, Allen Chin, Ralph Jones, Charles R. Morrison Sr., James & Melba Nixon, Nancy Priest, Theodore K. Schlosberg, and Mabel L. Sturgis with Helen French Welch. The Hall of Fame Committee has a long list of qualified candidates submitted by the public for its consideration in future inductions. The 13 members of the 2022 Hall of Fame selection committee are planning the induction ceremony for October 7, 2022. Hall of Fame members are chosen based on demonstrated talent, ability and accomplishments in their field. They have made a significant impact on the town, state or nation, and brought pride and recognition to Westfield. Historical Society members and the public at large are encouraged to submit profiles of persons believed to be strong candidates for the Westfield Hall of Fame to the Westfield Historical Society, P. O. Box 613, Westfield, NJ 07091.

Photo courtesy of Julian Hershey