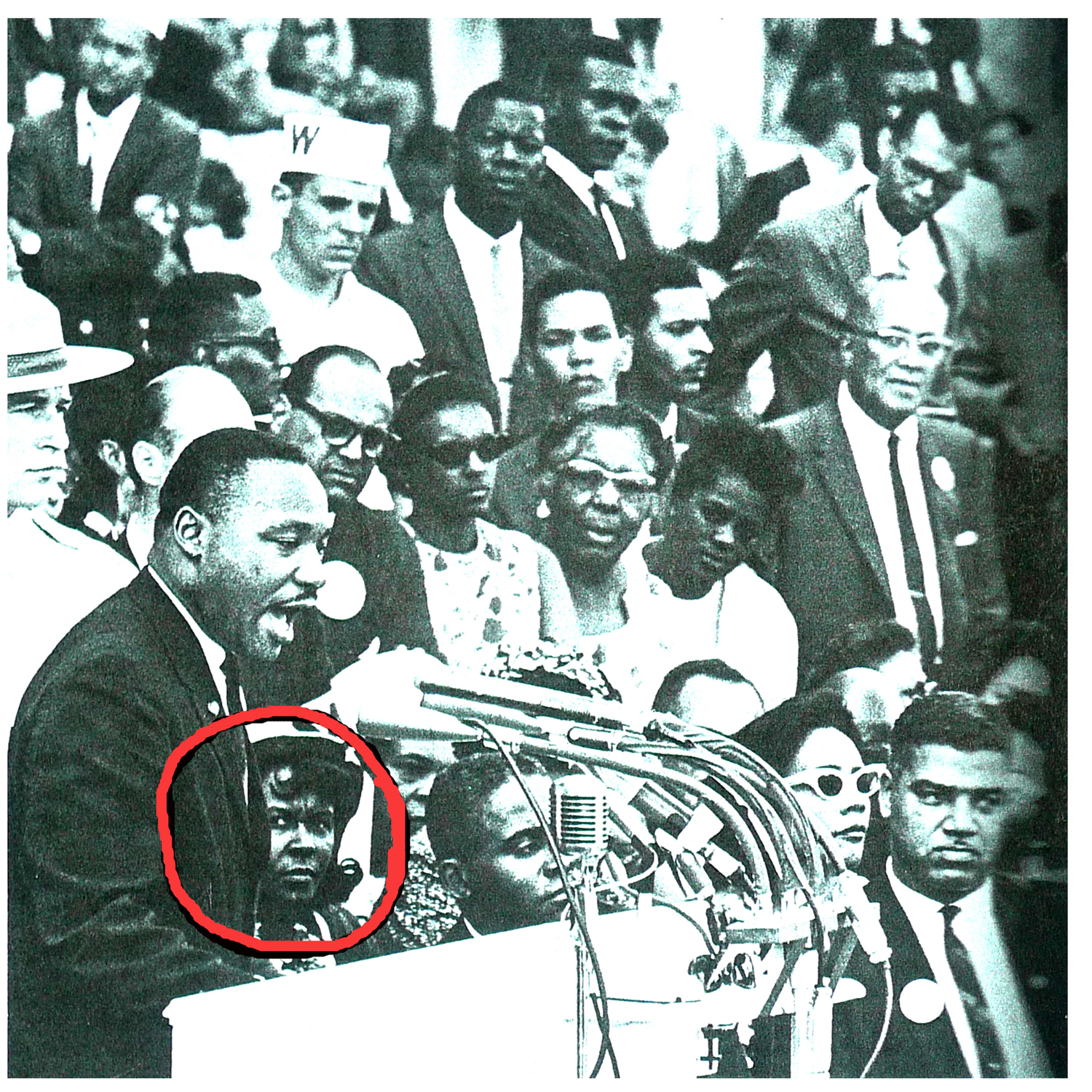

(above) Dr. Deborah Cannon Partridge Wolfe

Dr. Deborah Cannon Partridge Wolfe (1916-2004)

Submitted by Jean Kreiling, Cranford Historical Society

At birth, she was named Olive Deborah Juanita Cannon. Later she was known as Deborah and still later, because she was married twice, her name became Deborah Cannon Partridge Wolfe. She was born in Cranford on December 22, 1916 in her family’s home at 62 S. Union Avenue. The house stood on the corner of Lincoln Avenue across the street from what was then a 9-hole golf course and is now Lincoln Park. At the time, the population of Cranford was about 3,000.

(above) Dr. Wolfe’s father Rev. David Wadsworth Cannon was a chaplain during World War I.

Wolfe was the youngest child of the Reverend David Wadsworth Cannon, a graduate of Princeton Seminary and his wife Gertrude Moody Cannon, a graduate of Evangel Theological College. Reverend Cannon was the pastor of the First Baptist Church on High Street and his wife was the principal of the Rice Memorial School in New Brunswick. Education was of the utmost importance to the Cannons and even though they were poor, there were always plenty of books in the house. Deborah had two siblings, a brother David and a sister Mary. They were all exceptional students and when they graduated from Cranford High School, each of them went on to earn a doctorate. This was quite unusual at a time when few Blacks went to college.

Reverend Cannon had been called to serve at the First Baptist Church in 1911. When he and his wife arrived in Cranford, they found that the church had no parsonage. They had to search for a long time before they were able to find a home to buy. Wolfe loved this home and while her career took her to many places, she always returned to it and lived in it until she had to move to a retirement community.

The Cannons were hard working, innovative and forward thinking. These were important qualities at a time when the Black church had to take care of many of the social, in addition to the religious, needs of its congregation. During the long period between the Civil War and the civil rights movement, institutional racism not only kept African-Americans out of housing and good paying jobs, but it also prevented them from doing many of the things which other people took for granted. They often could not join clubs, participate in athletic activities, stay at hotels, eat at restaurants, get loans from banks or even sit where they wanted in theaters or trains. As a result, the Black church made every effort to help its people by duplicating services of the larger community from which they had been excluded.

In interviews, Wolfe and her mother Mrs. Gertrude Cannon Moody discussed the church’s activities. They said on Sunday afternoons and after Wednesday prayer meetings, their home was opened to children so they could play and socialize. All kinds of parlor games were played and the tablecloth was taken off the dining room table so that ping pong could be enjoyed. Refreshments were always served and there was singing around the piano. At the church on other days there was a dramatic club, social club meetings, dress-up events and different clubs that helped children to learn skills and practice manners. There was also a church bus to take people to picnics, hikes, skating parties and different affairs. To help children understand the effects of smoking and drinking, Mrs. Cannon created scientific demonstrations and she asked them to join a children’s temperance club and sign a pledge that they would never smoke or drink.

(above) First Baptist Church of Cranford

Help was also available to adults. If a man or woman never had the chance to go to school, the Cannons would teach them how to read and write. Reverend Cannon encouraged his congregation to buy their own homes so they could become independent. He also urged them to buy homes on different streets so that neighbors would interact and people would get to know and respect each other. (Wolfe would later say that the reason there was no de facto segregation in Cranford was because it had no ghetto.) But home ownership was difficult. The men could not get good-paying jobs and were forced to take landscaping and other part-time manual work. The women mostly had to do domestic work. These things didn’t change until a can factory opened in Kenilworth that began to employ Blacks.

Cranford’s schools, K-12, which Wolfe attended were desegregated. This was not true of the schools in southern New Jersey and even in many northern cities. Princeton, for example, did not desegregate its schools until 1948. Wolfe always praised the education she received in Cranford, but she also recounted some incidents of prejudice. She said she had been put back a year when she returned to grade school after recuperating from chicken pox. When Mrs. Cannon learned that this had happened to all of the Black children, but to none of the Whites, she complained to the principal and Deborah was returned to her class. In high school, when she wanted to learn how to play tennis, Wolfe found that Blacks were not allowed on the town’s courts. To help children like her, Reverend Allen who was then the pastor of the First Baptist Church, had a tennis court built on the church grounds. An incident that was especially painful to her occurred when Wolfe discovered that she had not been included in the photograph of the National Honor Society in her high school yearbook. After pointing out to the principal that she had always been on the honor roll and had better grades than some of her classmates in the photo, she was initiated into the society.

In 1933, Wolfe graduated from Cranford High School and enrolled at Jersey State College. To afford books and tuition, she tutored, gave piano lessons, did secretarial work and was hired by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to be both the principal and a teacher at a night school for adults at Lincoln School.

Mrs. Cannon told her that the National Council of Churches was looking for someone to teach the children of migrant workers in Maryland. These children had come to her attention during her travels to different towns to address classes about the dangers of smoking and drinking. Wolfe subsequently spent two summers teaching and doing community work with these children and their families. This experience affected her deeply and altered her thinking about education.

Wolfe was shocked to discover that the children could not understand what she trying to teach them. Never having been allowed to attend either the local schools or the churches, they had no experience beyond the crowded hovels in which they lived and had no idea what she was talking about when she mentioned goals and aspirations. From this Wolfe discovered the importance of understanding the backgrounds and beliefs of children in order to provide them with educational materials they could relate to and thereby begin to learn.

When Wolfe needed to do her student teaching, despite her superior grades, Cranford rejected her. She then turned to Westfield which accepted her. After graduating from college in 1937 she enrolled at Teachers College Columbia University and received a master’s degree. She then applied for a teaching job in Cranford. Unsuccessful, she applied to other schools throughout New Jersey, but none would hire her. It was a time when the only jobs African-American teachers could get were in the Black schools in southern New Jersey.

(above) Dr. Wolfe was on the grandstand with Dr. King during his “I have a dream” speech.

Mabel Carney, Wolfe’s Columbia professor suggested that she apply to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Carney wrote a letter of recommendation citing Wolfe’s exceptional abilities and Tuskegee offered her a position on the faculty. Tuskegee quickly recognized Wolfe’s talents and appointed her to be the head of both its education and graduate studies departments. In 1940, Wolfe married Henry Roy Partridge a Tuskegee professor. While her husband was away at war, she returned to Teachers College and in 1945 earned a doctorate in education. She then went back to Tuskegee and in 1947 gave birth to a son who was named after his father. Divorced in 1950, she returned to New Jersey and in 1951 she became an assistant professor of education at Queens College where she was the first African-American member of the faculty. Unable to get affordable housing near the college because of a no-Blacks policy, she stayed in Cranford and commuted two or three hours each way to Queens. In 1959, she married Estemore A. Wolfe, a teacher and businessman. This marriage ended in divorce in 1966.

Wolfe wrote articles on education, traveled extensively, lectured throughout the country and was active in many organizations devoted to education and civil rights. As her reputation grew, she came to the attention of Washington. In 1963, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. asked her to become the Chief of Education of his powerful Education and Labor Committee. After taking a leave of absence from Queens College, she went to Washington where she embarked on one of the most important tasks of her life which was to help to craft and move the Civil Rights Bill through Congress.

After 3 1/2 years in Washington she decided it was time to return to her professorship at Queens College and to resume her life in Cranford with her son. He was in his senior year at Cranford High School and she wanted to spend time with him. In 1970, Wolfe was the first African-American woman to be ordained by the American Baptist Association. In 1975, she became the associate pastor of Cranford’s First Baptist Church where her father had been the pastor. Her life had now come full circle. “I stand where Papa stood,” she said.

Wolfe retired from Queens College in 1986, but continued to be active on many fronts. She served on the New Jersey Board of Higher Education and was unanimously elected its chair in 1987. She also served on the Executive Committee of the United Nations Committee of Non-Governmental Representatives. Her accomplishments were so many that by the time she died in 2004, she had received 26 honorary doctorates.

This article was originally published in the Cranford Historical Society’s Spring 2016 newsletter, The Mill Wheel. It has been edited for publication here.